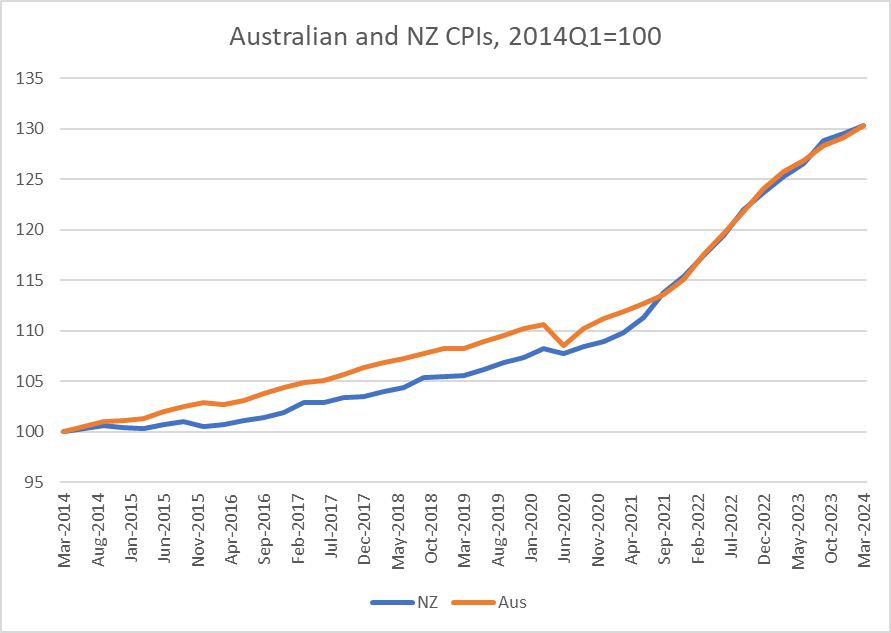

I got curious yesterday about how the Australia/New Zealand real exchange rate had changed over the last decade, and so dug out the data on the changes in the two countries’ CPIs. Over the 10 years from March 2014 to March 2024, New Zealand’s CPI had risen by 30.3 per cent and Australia’s CPI had risen by 30.4 per cent.

And that piqued my interest because the two countries have different inflation targets: New Zealand’s centred on 2 per cent per annum and Australia’s centred on 2.5 per cent.

So I drew myself this chart

Over the full 10 years, the two CPIs have increased by almost exactly the same amount, but they haven’t kept pace with each other steadily over that full period. Up to just prior to Covid, the Australian CPI had been increasing faster than New Zealand’s, as one might have expected given that the RBA had been given a higher inflation target than the RBNZ.

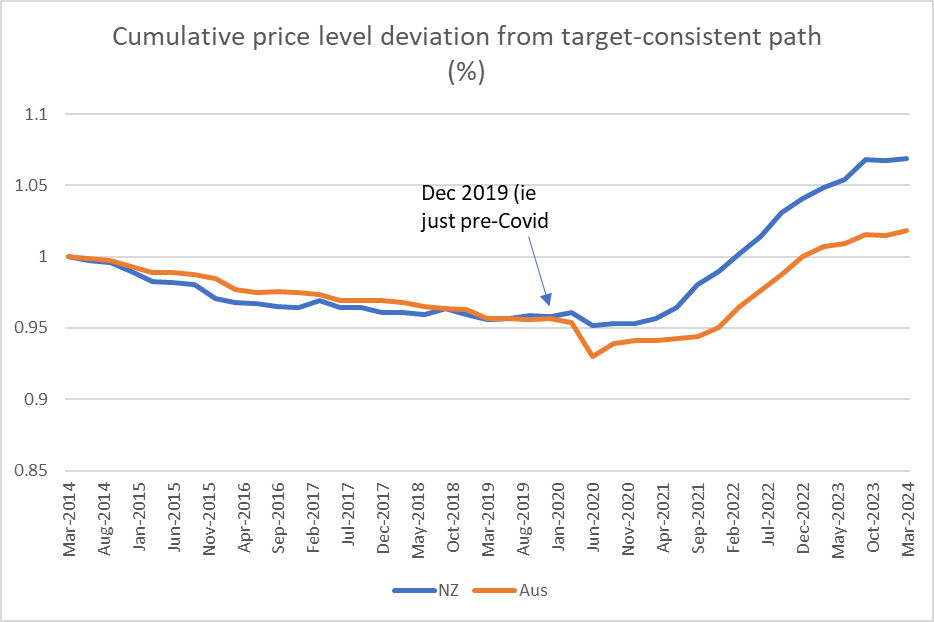

Now, before anyone objects, I should get in and note that in neither country is there a price level target. But if economies are subject to fairly similar shocks over a period of time one should normally expect a country with a higher inflation target to have experienced a higher cumulative price level increase than a country with a lower target.

Over the 10 years here is Australia’s CPI relative to the price level that would have been implied by being consistently at target midpoint

and the same chart for New Zealand

And in this chart I’ve put it all together

Over the half-decade or so to the end of 2019, the RBA and the RBNZ had both ended up undershooting (on average) their targets by about the same extent. If you look closely, the RBNZ was undershooting more earlier, and the RBA more towards the end of the decade, but there wasn’t a great deal in the difference.

But where the difference really becomes apparent is in the years (four of them) since Covid hit. Over that period, the RBNZ has generated/tolerated much more of an increase in the price level, in excess of what is implied by their target, than the RBA did. (And for those – like Orr – who like to try distraction with things like oil shocks, wars and rumours of wars, and supply chain disruptions, Australia faced all those too.)

There is a lot of focus in Australia – and apparently reasonably enough – on whether the RBA has yet done enough with monetary policy. It has certainly been puzzling that they reckoned they could get away with materially lower policy rates than in other Anglo countries, in the face of (still) near-record low rates of unemployment and a quite stimulatory fiscal policy. But so far, and overall, they’ve done a bit less badly than the Reserve Bank of New Zealand through the last four years taken together.

It remains somewhat remarkable how little serious accountability there has been for serious Reserve Bank policy errors, for which now pretty much everyone (except them) is paying the price. in one form or another.

(By the way, for anyone interested, the NZD/AUD exchange rate averaged 0.933 in the March 2014 quarter and 0.932 in the March 2024 quarter, so over that particular 10 year period there was no change in the real exchange rate at all.)

Michael Reddell spent most of his career at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, where he was heavily involved with monetary policy formulation, and in financial markets and financial regulatory policy, serving for a time as Head of Financial Markets. Michael blogs at Croaking Cassandra - where this article was sourced.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.