Systemic racism or an inconveniently multifaceted set of problems requiring uncomfortable conversations

It is a fact that the life expectancy of Māori is lower than New Zealanders of European descent. It is also a fact that the life expectancy of New Zealanders of European descent is lower than that of Asian New Zealanders.

Disparities exist. Some of these are driven by factors we cannot necessarily control like genetics and predispositions. Others are driven by factors the state cannot control, but the individual can, like diet and lifestyle. Then there are the factors like access to healthcare (geographic and cost barriers), economic deprivation, and overall resourcing of the system that fall squarely in the lap of the state. It is right that New Zealanders should have high expectations of the Government in terms of delivering on that third set of factors. But we need to have an honest conversation about the things we cannot blame on race and systemic bias. We also need to call out the ideological and nonsensical reporting on these issues that only perpetuate the myths that are holding us back from addressing health disparities honestly and effectively.

Following the sadly premature death of Te Pāti Māori MP Takutai Tarsh Kemp as a result of end stage kidney disease (ESKD), I knew there would inevitably be articles about the health disparities between Māori and other New Zealanders. I knew we would be told that systemic racism is responsible for these disparities, but no solutions would be proffered nor any frank discussions had about what can be done to change the situation from the perspective of Māori and the state. It is the laziest of ways to address a chronic problem. Point to a bogeyman that cannot be properly quantified or even described. Virtue signal done for the day, now onto the weather.

A couple of days ago, this article in the New Zealand Herald fulfilled my predictions.

Following the sadly premature death of Te Pāti Māori MP Takutai Tarsh Kemp as a result of end stage kidney disease (ESKD), I knew there would inevitably be articles about the health disparities between Māori and other New Zealanders. I knew we would be told that systemic racism is responsible for these disparities, but no solutions would be proffered nor any frank discussions had about what can be done to change the situation from the perspective of Māori and the state. It is the laziest of ways to address a chronic problem. Point to a bogeyman that cannot be properly quantified or even described. Virtue signal done for the day, now onto the weather.

A couple of days ago, this article in the New Zealand Herald fulfilled my predictions.

There were many things that frustrated me about the article, including the fact that Jonah Lomu is Tongan, not Māori, but was used as one of the main examples. I was particular perplexed by the section headed Māori organ donation:

Dr Curtis Walker, a Kidney Health New Zealand board member and nephrologist who specialises in the diagnosis, treatment, and management of kidney diseases and conditions said it was a cultural myth that Māori and Pacific people would not donate organs.

Figures are not kept on the ethnicities of donors, but “there is a great willingness among Māori to donate,” he said.

“Back in the day some would see this as tapu and not to share organs but these days Māori are very accepting of organ donation.

“We are seeing an increase in Māori donors.”

What bothered me is that Dr Curtis Walker says there is not data available on the ethnicities of donors in order to discredit the “myth that Māori and Pacific people would not donate organs”, but then he goes on to make emphatic statements including that we are seeing an increase in Māori donors. How is it possible to know this when the doctor has just told us there are no figures recording this information?

I decided to find out for myself. I wanted to better understand the differences in causes, treatments, and outcomes for patients with kidney disease in New Zealand based on ethnicity. Is systemic racism this undefeatable force lurking in every corner of our health system? Are we powerless to make changes on individual and societal levels? I spent my Saturday night taking a dive into New Zealand’s health system. Don’t judge; I find this stuff really interesting.

Kidney Disease in New Zealanders

I started with establishing some background knowledge. It’s estimated that around 550,000 Kiwis (roughly 1 in 10 adults) are living with some form of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), though half are likely undiagnosed.1

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an umbrella term used to describe any long-term condition that adversely affects kidney structure and function. However, declining kidney function is also a natural part of the ageing process. It is estimated that by the age of 70 years approximately 30% of the population will meet classification criteria for CKD.

Approximately 1,000 New Zealand adults are diagnosed with end stage kidney disease (ESKD) each year, and about half of that number begin dialysis treatment annually.2

In terms of total numbers, more non-Māori/Pacific New Zealanders are diagnosed with ESKD, but when adjusted to a per million population (pmp) the prevalence in both Māori and Pacific populations is higher.

For example, when it comes to the number who underwent kidney replacement therapy in 2023, the Pacific population had the highest rate (478 pmp), followed by Māori (205 pmp), and non-Māori/Pacific groups (82 pmp).3 Most data is focused on these three ethnic groupings so I’ll stick with them, though I note that South Asian populations are highly represented in kidney disease statistics.

The type of kidney diseases differs between populations also. Diabetic kidney disease is the most common type in all populations, but in Māori and Pacific patients the split is more pronounced with 66% and 68% (respectively) of kidney disease primarily related to diabetes. For non-Māori/Pacific patients 29% is diabetic closely followed by 26% Glomerular disease.

Glomerular refers to conditions that cause inflammation or damage to the glomeruli, the tiny filters within your kidneys responsible for cleaning your blood. This damage can stem from various sources, including infections, autoimmune diseases, genetic disorders, certain medications, and systemic conditions like high blood pressure.4

Kidney donations

The New Zealand Herald reported that Te Pāti Māori MP Takutai Moana Tarsh Kemp “was one of 400 people on the national kidney transplant waiting list.”5

I found that there are stark differences in the type of kidney donations patient demographic groups receive. It is unsurprising that questions are asked about why these differences exist. Kidney transplants are divided into those from deceased donors, living donors (related), and living donors (unrelated). When we talk about the transplant “waiting list” this is primarily about those waiting for people to die who have consented to donate their organs. Only very rarely a kidney will go to someone on the list from a “non-directed donor” who is alive and decided to donate one of their kidneys to someone they do not know.

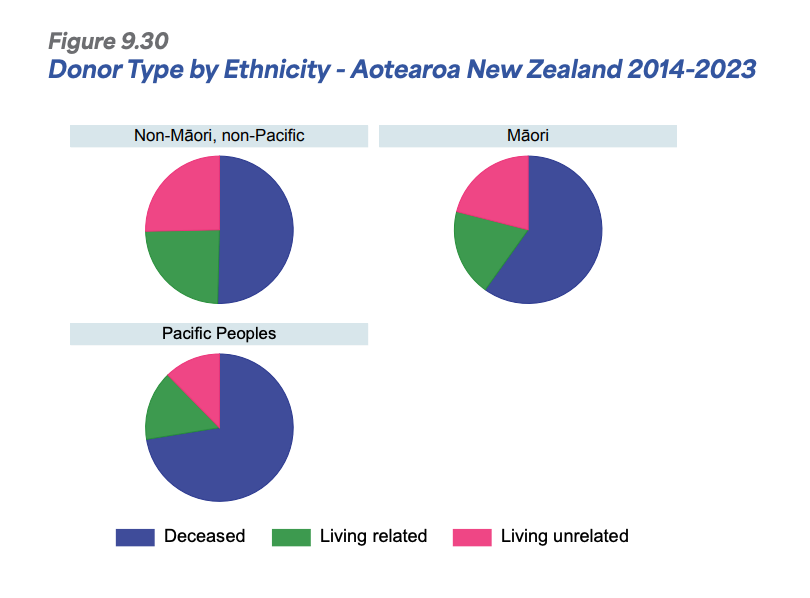

As Dr Curtis Walker told the Herald, we do not have data on the ethnicities of donors (that I could find). But we can kind of backwards engineer the equation to make some informed deductions. In the ANZDATA ANNUAL REPORT 2024 | Chapter 9 - Kidney Failure in Aotearoa New Zealand, I found information on the breakdown of deceased/live (related)/live (unrelated) kidney donations received by each ethnic group. Using this we can see how much the populations in each group are relying on waiting for a donation from someone unknown to them. The reason they would be doing this is because they have not been able to find a donor willing and compatible in their family/whānau/friend circles.

As shown in the figures below, the majority of Māori recipients of kidneys receive them from deceased donors. Pacific patients are even more likely to have received a donation from a deceased donor.6

The below figures break this data down by year (note that the Y axis on the non-Māori/Pacific graph is numbered differently to the other two graphs).

Click to view

The question the differing splits raises is why are Māori and Pacific patients more likely to need to rely on deceased donors? If Dr Curtis Walker is correct that it is a myth that there is a cultural reluctance in Māori to donate organs, then there must be another reason that Māori are not receiving as many live donations.

Getting a match

The waiting list leaves a lot up to chance. To be placed on this list, patients must be healthy enough to be deemed to have at least an 80% chance of 5‑year survival, based on age, heart health, cancer status, comorbidities, and time on dialysis.7 There are usually over 400 people active on the list and around 100 deceased-donor kidneys available each year. Allocation is based on time waited and compatibility.

Health New Zealand says:

“Most people will wait for several years. Sometimes this is because of your blood group or antibodies. Some people on the waiting list may never be offered a kidney from a deceased donor.”

…

“Kidneys are offered to people based on 2 things. First who has been waiting the longest time on dialysis and secondly the best match.

There is no way of guessing the blood group of the next donor and what antibodies a person needing a transplant might have against that kidney.”

The deduction we can make from this information is that the best way for someone to improve their odds of receiving a kidney donation is to find someone willing to donate one.

Directed living donations (from family or a friend) do not use a waitlist. There is a thorough process designed to protect both donor and recipient, ensuring safety, voluntary commitment, and medical suitability. Donors must be 18 years of age (some sources say non-directed altruistic donors need to be 21, but I haven’t been able to confirm). They have to complete a health questionnaire covering personal and family medical history and some of the key reasons they might be disqualified at this stage are: high blood pressure, diabetes, heart, liver, or kidney disease, cancer, mental health issues, and obesity.

Next the donor’s compatibility with the recipient is tested. An ABO blood group test is done to confirm blood-type compatibility. If incompatible, the donation cannot go ahead, but they could join the paired kidney exchange.8

Then comes the medical and psychosocial evaluations which include blood and urine tests to assess kidney function and screen for infections, heart and lung checks, imaging (CT angiogram, ultrasound) to examine kidney structure and vasculature, cancer screening, and a psych evaluation to establish that the decision is informed and voluntary.9

If all is well, the next step is immunological testing. This is HLA tissue typing and crossmatching to ensure immunological compatibility and a negative crossmatch is required for direct donation. This is about immune system compatibility because even a perfectly functioning kidney will be rejected if the recipient’s immune system sees it as foreign. HLA typing checks for a genetic match and crossmatching checks if the recipient’s immune system is likely to reject the kidney.

According to my research, family/whānau and blood relatives are more likely to be compatible for kidney donation, especially when it comes to HLA matching, but it's not guaranteed. Our HLA markers are inherited from our parents. So, siblings have about a 25% chance of being an excellent HLA match (called a “full match”), and about a 50% chance of being a half match. Parents and children will always be a half match (they share one HLA set). Brothers, sisters, and parents are statistically more likely to be good matches than unrelated people, but cousins or extended whānau can also be matches, especially in closely connected gene pools.10 But even if a relative is an HLA match, they also need to have a compatible blood type for direct donation.

Why are Māori and Pacific patients getting fewer live donations?

Aside from cultural reluctance, what are the barriers to these patients accessing donations from relatives and friends? Well, my late night research led me to some interesting but depressing conclusions. They don’t disprove that reluctance is an issue but they definitely provide some credible other reasons why accessing these donors is more difficult.

As we established, the best place to start looking for a donor is ones own family and while on average Māori and Pasifika families are larger and so theoretically should have more possible donors, this often not the case. This is because Māori and Pacific potential donors are more likely to be disqualified at the beginning of the process due to high blood pressure, diabetes, heart, liver, or kidney disease, cancer, mental health issues, or obesity. The very same factors that contribute to the patient developing ESKD are likely present in many of their family members.

In ANZDATA ANNUAL REPORT 2022 | Chapter 11 - Kidney Failure among Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand, it is highlighted that diabetic kidney disease contributes to 67% of Māori kidney failure and that this makes it more likely that whānau will experience similar comorbidities disqualifying potential kin donors.

I also found a 2013 study called ‘Finding a living kidney donor: experiences of New Zealand renal patients’ in which “One hundred and ninety-three patients on the New Zealand waiting list for a kidney transplant responded to a postal survey about live transplantation.”11 This study also found that Māori and Pacific patients were less likely to receive offers from potential living donors. Major barriers included donor medical unsuitability, including health problems that ruled out donation. Other additional studies identified that donors’ financial losses and health impacts were also barriers to familial donation.12

Systemic racism

Systemic racism is pointed to as the root cause of financial and medical suitability barriers in many of the papers and reports that I found. I examined this 2022 paper more closely to try to understand: “We Need a System that’s Not Designed to Fail Māori”: Experiences of Racism Related to Kidney Transplantation in Aotearoa New Zealand.

This paper is a powerfully argued contribution that illuminates the many ways racism is perceived to exist throughout the kidney transplant process for Māori. It is based on qualitative research and that has strengths and weaknesses. The personal quotes and insider experiences are valuable and serve to demonstrate there is much to be improved upon in terms of patient and family care, but the paper does not provide direct evidence that the system is intentionally designed to fail Māori.

It places blame generously at the feet of a conspiracy of racial animosity without engaging seriously with the rationale for transplant criteria nor resource constraints that might explain some systemic outcomes. It starts with the conclusion that the system fails Māori and interprets all findings in light of that.

The framing of malice within the people in the system risks undermining the credibility of the research among those not already ideologically aligned with concepts promoted by critical race theory.

One section of the paper that warrants a closer look, however, is the part that focuses on the implications that the BMI (Body Mass Index) policy in New Zealand’s kidney transplantation system has for Māori. Strict BMI cutoffs are used to determine eligibility for transplants (commonly around BMI of 35). This automatically excludes many Māori patients and potential living donors due to higher average body weight across the population.

I am on board with the authors’ argument that this policy should be less broad and take into account genetic and bodily differences between races. Many of their study participants described the BMI policy as "one-size-fits-all" and racist in effect, even if not racist in intention. The policy treats all bodies the same, ignoring ethnic and physiological differences, such as body composition and fat distribution.

However, they lose me when they start attributing this to colonisation and focusing on oppressor/oppressed narratives. They treat the BMI threshold as if it is an arbitrary exclusion tool wielded to keep Māori off the transplant list, ignoring that BMI is widely, and globally, used to assess surgical risk. It's not unique to New Zealand or targeted at Māori. It also ignores medical liability and that doctors are accountable for outcomes. Transplant failure due to obesity-related complications is a legitimate concern.

We should examine if some willing Māori donors are being rejected based on BMI alone, even when they are otherwise healthy. Unnecessarily compounding the shortage of suitable donors for Māori patients would be awful, especially given the importance of genetic and immunological compatibility within ethnic groups.

As an aside, I was horrified to read that some patients are expected to lose significant weight while managing end-stage kidney disease. Weight loss is hard and complex at the best of times let alone when you are suffering ESKD. This quote broke my heart:

“They told me to come back when I was skinny. I felt like they didn’t want to help me unless I became someone else.”

Nonetheless, that the entire paper is steeped in critical race theory is not helpful. Every problem, be it communication breakdown, lack of transplant education, or feelings of shame, is interpreted as an expression of racism. It reduces complex medical triage decisions to a simplistic power struggle. There’s no exploration of alternative explanations, and little attempt to distinguish structural failings from race-specific prejudice.

While the voices of Māori patients must absolutely be heard and qualitative studies are one way to do that, ideological frameworks that blame bogeymen instead of tangible inadequacies for health disparities won’t effect real change.

So what do we do?

Dr Curtis Walker, from the Herald article, argues that since 60-70% of kidney disease, and failure, is preventable, especially in Māori and Pacific populations, early detection and intervention is how lives can be saved.

“This really starts with access to good primary health care and staying away from the crap calorie-laden fast food available,” Walker said.

This is not the answer anyone wants to hear. For individuals losing weight and keeping it off is incredibly difficult. Having lost 60 kilograms recently I know this all too well. It is even harder when economic deprivation limits food choices, makes it more difficult to make positive lifestyle changes, and rules out expensive but effective specialist support. For governments, tackling the obesity and sedentary lifestyle problems plaguing our populations is not just a daunting task, it is also astronoically expensive. In both cases, we need a mindset shift. Weight loss is hard, but being on dialysis and then dying decades too early is harder. Funding preventative lifestyle-based interventions is very expensive, but funding more and more Kiwis to receive dialysis and undergo the many, many other medical treatments that might be required as a result of obesity, diabetes, and associated illnesses is far more expensive.

It is the solution we all know is needed, but avoid because it requires challenging conversations, personal responsibility, and changes in government intervention at a transformational level.

The populations most impacted, like Māori and Pacific populations, need to stop smoking and drinking, improve their diets, and move more. But that is overly simplistic. Those who point to external factors that make this solution difficult to achieve are correct. Poverty does make it harder to make lifestyle changes. Level of education does impact knowledge and ability to self-direct behaviour change.

In my view, the problem cannot be boiled down to either personal responsibility or systemic failing. Both individuals and our government have roles to play. Crucially, our government departments need to stop playing critical theory games where they burn through precious taxpayer funds on navel-gazing about the systemic racism bogeyman. Tinkering around the edges needs to stop also. We need explicit acknowledgement that obesity and associated lifestyle issues are causing the bulk of our health problems and that as a country we need to do something about it.

New Zealand needs systemic change. It just isn’t the kind that academics and the news media want to talk about.

Ani O'Brien comes from a digital marketing background, she has been heavily involved in women's rights advocacy and is a founding council member of the Free Speech Union. This article was originally published on Ani's Substack Site and is published here with kind permission.

No comments:

Post a Comment