The Treasury yesterday hosted the first in their new series of guest lectures, under the broad heading “Fiscal Policy for the Future”. In introducing the series Dominick Stephens, Treasury’s chief economist, told us that the focus would be on three sub-headings: policy dimensions around fiscal sustainability, the potential stabilising role of fiscal policy, and ideas around value for money. Which sounds fine I suppose, but it perhaps wasn’t a great example of reading the times that the first lecture was about an idea that would, when it was used, involve the Crown simply giving away a lot more money (automatically).

The guest lecturer was the left-wing (a description she embraces) American economist Claudia Sahm. Sahm was formerly an economist at the Fed and these days seems to divide her time between consulting and being chief economist for a US funds management firm.

Sahm is best known for the Sahm rule US recession indicator

Click to view

Sahm is best known for the Sahm rule US recession indicator

Click to view

She didn’t develop the indicator simply for analytical interest but (as she reminded readers in a recent Substack) with a policy proposal in mind

The idea being that when the recession indicator threshold point is met, the IRS would mail out checks automatically, to lean against the incipient downturn by boosting consumer spending. It would be, in her words, a quasi automatic stabiliser

(The “automatic stabilisers” are the extent to which government budgets vary with economic cycle without any discretionary policy changes – you can think of unemployment benefits, but typically the tax side of things is much more important. We don’t have lump sum taxes, rather governments share in the gains/losses when wage bills, spending, and profits rise/fall. Relative to a lump sum taxes benchmark, the actual way we design tax systems – proportional and, in respect of income tax, progressive – tends to dampen economic cycles a bit.)

Ever since Covid Treasury seems to have been freshly keen on a more active role for fiscal policy (Stephens indicated yesterday that they are looking at making the stabilisation role of fiscal policy the topic for their next Long-Term Insights Briefing). I’ve written previously about a conference Treasury (and the RB) hosted three years ago, before it was really appreciated what a mess Covid macro management and associated misjudgements had wrought. At that point, Treasury people from the Secretary down were very upbeat, partly as a result of misapplying the hardly-surprising “insight” that if you forced people to stay home and, in many cases, not work, income support was going to be done a lot more effectively using income support tools than via monetary policy. As if it was not ever so – we provide income support to unemployed people using direct Crown payments too, rather than simply relying on monetary policy to sort everything out in the end. They were at again yesterday. Yes, there are plenty of things governments need to directly spend money on, but when it comes to macroeconomic stabilisation it is very much still “case not made”. But in fairness to Stephens, he did emphasise that if many people are Keynesians in foxholes (nasty recessions), rather fewer of them were keen on using fiscal policy to take away the punchbowl as the party was in danger of overheating. On yesterday’s showing, Sahm among them.

Anyway, that was all by way of introduction. Treasury seems to have been paying Sahm (over a period of several months) to develop her ideas in a way that might be applicable in New Zealand. If I was inclined to wonder whether this might not have been a potential budgetary saving (US macro consulting economists probably don’t come cheap), I actually found the lecture quite useful, mostly in shifting me more firmly into the camp of regarding the quasi automatic stabiliser idea as neither very workable nor very useful in the New Zealand specific context, using New Zealand macro data, and the experience of New Zealand recessions.

Sahm started by claiming that New Zealand had worse stabilisation challenges than many other (advanced?) countries, claiming that we had “really volatile output”. I wasn’t quite sure what she was basing that claim on, and just went back and dug out the OECD series of quarterly changes in real per capita GDP over the last 30 years (the period for which the data is fairly complete across the whole membership). New Zealand doesn’t really stand out – actually the median country for the variability of quarter to quarter changes over that period. What is perhaps more notable – and relevant here – is that the United States had the second lowest standard deviation of any of the OECD countries over that period. (It is also worth bearing in mind that many international comparisons, notably the OECD, use the expenditure measure of GDP, which used to be much more volatile than it has since become – an open question as to whether that is a reflection of changing reality or just better measurement by SNZ.)

Sahm is keen on the automatic stabilisers. She claims New Zealand’s are more effective than average, although in the past I’ve seen people reach the opposite conclusion (for the good reason that we have flat rate unemployment benefits rather than income-related ones, and that our tax system is not highly progressive, and our taxes as a share of GDP are not overly high). But whatever useful impact the “automatic stabilisers” have in dampening the extremes of economic cycles, it is important to remember that those features of the tax and transfers systems were put in place on their own specific individual merits, and any macroeconomic stabilisation benefits are at best nice-to-haves. We have unemployment benefits because we think people (and their kids) shouldn’t starve. We have progressive taxes because of conceptions of fairness, and proportional rather than lump sum ones for similar reasons. We have bigger governments in some countries than in others not primarily from macroeconomic stabilisation considerations, but because of differing conceptions – fought through political processes – about the role of the state.

By contrast, what Sahm is proposing is a fiscal tool that would exist solely for macro stabilisation reasons. It really is a quite different beast. To be fair to Sahm, she argues that her tool isn’t necessarily a case of more total fiscal outlays in downturns, but different or better ones. But you get the sense that her personal politics leans in the direction of bigger government rather than smaller, and as we shall see – whatever might have been the case in her US calibrations – in New Zealand it doesn’t look as though it would have worked that way.

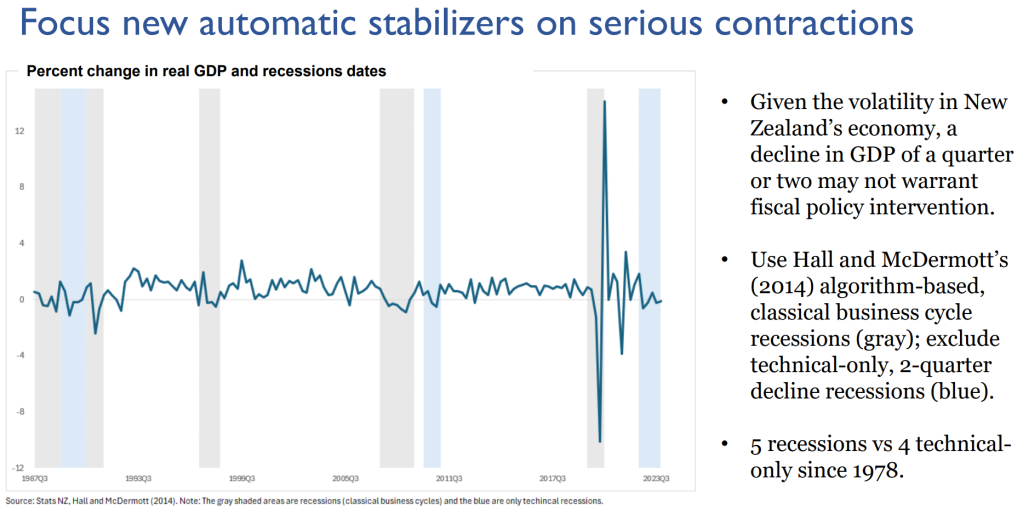

Her New Zealand starting point was to identify the agreed upon recessions, using the official New Zealand data.

Click to view

One might quibble, but lets take that list and move on

She then trawled through the New Zealand data looking for a rule that would be timely, simple, easy to understand (and legislate), involving reliable data, and free from external influence. This is the proposed rule she came up with

Click to view

You will quickly see that it is quite a lot more complex than her US rule (which has just one variable – the unemployment rate – to trigger similar sized (in aggregate) payments.

Who would be eligible? Her basic proposal was that payments (around $1000 a head [UPDATE altho I suppose larger if children were excluded; she didn’t clarify one way or the other]) should be made to the bottom 80 per cent of people by income (no doubt greatly welcomed by middle class kids doing after school jobs, their older siblings at university, and the retired). In her time working with Treasury she had, it seemed, been regaled with stories of the previous government’s “cost of living” handout, and she (fairly) noted that the advantage of pre-positioning an instrument is that you can sort out all/most of those sorts of issues in advance.

Where I started getting uneasy was with the consumption indicator (I wasn’t clear whether she was using private consumption or total but what follows is relevant either way). First, as she acknowledges, she is finding empirical regularities (data mining might be a bit unfair) not laws of nature, and it is over a sample of only five recessions, (two of which really ran into each other, one of which was very very unusual in nature). Perhaps the thing that most surprised me was that there was no sign she had done her analysis using real-time data – which is what any automatic instrument would have to be keyed off. She mentioned the point in passing, but surely between Treasury and SNZ they could have got her the real time (ie first contemporaneous release) data to check?

Those revisions matter. As just an example, on a very quick Google around the eve of the 2008/09 recession this was how the Treasury March 2008 Monthly Economic Indicators report saw the latest GDP numbers

Click to view

That was production GDP, up by an estimated 1 per cent. The current official estimate for that series for that quarter is an increase of 0.13 per cent.

(In passing I would note that anything that is a legislated mechanical rule then puts a great deal onus on the processes and capability and integrity of the organisation producing the data. Their staff and management will know that a great deal may rest on one tenth of a decimal point in some circumstances. In years gone, I would probably have played that down as an issue in New Zealand, but…..SNZ has been in the headlines in the last 10 days or so for reasons that don’t fill people with confidence in their integrity or capability, and in recent decades SNZ has been run by generalist public servants from the SSC/PSC stable, not fierce statisticians. It wouldn’t be my biggest worry by any means, but….)

But much the biggest issue is that inflation line in the rule. I’ve not seen anything similar in her US proposal. The general idea is that if (core) inflation is high you really don’t want to be adding automatic stimulus to the fire (any more than discretionary bits, like the “cost of living payments”). As Dom Stephens pointed out, there is an argument the restriction isn’t tough enough even as Sahm expressed it: after all the Reserve Bank is supposed to be aiming at 2 per cent, and if inflation is above target overall macro policy is still supposed to be bearing down on inflation (although here I would note the lags, and if macro policy isn’t adjusted until inflation is all the way back to target midpoint it is almost certainly rather too late). But lets stick with Sahm’s version.

She presented this chart (Treasury sent out her presentation to attendees but hasn’t yet put it on their general website)…

Click to view

…and claps herself on the back. Her fitted rule, she claims, triggers in all the recessions except the 1997/98 one (which had as much to do with drought and bad domestic monetary policy as Asia). Unfortunately, I think she has been misled by some of her data, and doesn’t have any real domestic context. As a starter, from the bottom half of her table (“technical recession”) the 1989 sharp fall in consumption was from a base quarter immediately prior to an increase in GST, so at very least you’d need to adjust the rule for such (easily observable) events.

But what about the real recessions (top half of the table)? There is some ambiguity about the 87/88 event as her table says N to automatic payments but her text seems to say yes. But either way, there is absolutely no way that macro policymakers in early 1988 would have been wanting to add fiscal stimulus (automatic or otherwise). Inflation (headline and core concepts) was coming down but was far too high (for the Bank and for ministers), and every single one of the regular Reserve Bank reports in those days called for more fiscal consolidation to ease the pressure on monetary policy and the real exchange rate. Same goes for the 1991 recession. We were still trying to drive down inflation (it was too high relative to the new official target) and fiscal policy was all in a flurry by the averted threat of a double credit rating downgrade. Aggressive fiscal consolidation was the order of the day, both for fiscal reasons (primarily) but also to ease pressure on monetary policy),

Skip over 97/98 for the moment and we come to 2008/09. The sectoral model of core inflation – probably the best retrospective indicator of core trends – was well above 3 per cent all through 2008 and into 2009, so although I’m not sure what core measure Sahm is using in the table, inflation certainly wasn’t anything like acceptable to the Bank in the early days of the recession (Sahm’s focus). It was a year of fiscal expansion……but mostly because (a) Treasury misjudged the permanence of the high levels of government revenue at the peak of the boom, and (b) it was election year and the government was losing (and presumably preferred specific own-brand giveaways to mechanised ones). Even had the rule been in place, it probably wouldn’t have triggered before final Budget decisions were being made in April and early May 2008.

As for Covid, if I was trying to design an automated rule I’d just take the Covid period out of my sample. The (discretionary) wage subsidy – which might have been too generous, but did its job – was put in place in late March 2020, months before the Q1 consumption data were available. Not only would the rule have been far too late to trigger, but in the specific circumstances it would have been too small to be relevant (swamped by the size of the wage subsidy). And, as it turned out, the last thing that was needed in 2020 was more encouragement to people to spend…..when the overall policy response helped generate the worst breakout in inflation for decades.

She calls the current episode a “technical recession”, but the unemployment rate has risen already by more than a full percentage point and per capita GDP is down as much as it was in 2008/09 (and consumer spending has been very weak). So it feels like another downturn when the rule triggered but payments would not sensibly have been made because…..inflation.

It was Dominick Stephens who pointed out recessions are sometimes the solution (to inflation) not the problem to be resisted. And I think that does mark our experience out at least somewhat from the US – notably we went into the severe 2008/09 recession with a pre-existing inflation problem, and they did not.

So, curiously, what we are left with is that I can think of only one episode in the last 37 years (the data sample) when triggering the rule and making payouts might have been helpful (and I stress “might” because she isn’t modelling responses, or comparing alternatives), and that is the one of her real recessions where payments would not in fact have been made: the 1997/98 episode. Which seems a bit awkward for the proposal.

And that is before we start on the other problems with the scheme.

For example, if one could identify a new and reliable rule – for indicating that the economy was probably in recession – why not just (a) advertise it widely, and (b) pass it on with a strong commendation to the central bank MPC. If it is a great and reliable rule (a) the Bank would be likely to use it in some form or other, and (b) the markets and the public would recognise that conditions were likely to ease, and respond accordingly. And to turn things on their heads, if there is a preloaded fiscal response, doesn’t that make it more likely that the central bank will be even slower than usual (this isn’t personal to the RB, central banks generally tend to be too late) to react, relying in part on the coming fiscal hit to buy them a bit more time to wait and see? A realistic assessment of such a policy proposal would need to make allowance for those sorts of interactions.

And then there is politics. Why would any political party or coalition want to preload lump sum handouts, rather than (a) look to the RB to do its job, and (b) keep the fiscal fuel for its own spending or tax cutting priorities (and perhaps again this is a difference to the US: here the government automatically (by construction, having supply) has a majority for its own budget plans? And why would much of the public think that big handouts to beneficiaries, high school kids, the retired etc would be a great idea at a point in the cycle where – again by construction – the unemployment rate is perhaps only a little off cyclical lows – and some of those lows (as recently) may have been quite extremely low. (This is, incidentally, one of the conceptual problems with the rule – which is just based on empirical regularities. Unemployment rates do drop below sustainable levels, well below at times. There is no good reason to think that additional policy stimulus is required just because the unemployment is finally heading back towards some sort of NAIRU.)

Monetary policy isn’t perfect. Our central bank these days is certainly anything but. But the case for looking beyond monetary policy for cyclical stabilisation just hasn’t really been made convincingly, and – particularly here in the New Zealand case – a simple automated rules looks to have been as unfit for purpose as was the idea (touted a bit in the US) of having the Fed mechanically implement a Taylor rule.

Oh, and then there was the profound asymmetry. There is nothing in this sort of rule – or even a readily conceivable alternative one – that could credibly operate on the other side of the cyclical; pulling money out of the system according to some rule. It really is easier to give money away than to take it back. Much better to keep fiscal policy doing what it does best, and leave cyclical stabilisation efforts to the central bank (a case that, admittedly, would be more compelling in New Zealand were the central bank and its key public faces not so egregiously bad, and unwilling ever to admit or learn from inevitable errors).

But, as I say, I found it useful to think hard about Sahm-type rules in the specific context of New Zealand and its experiences in recent decades.

PS. Finally, I thought I’d take a look at the US Sahm rule indicator. It isn’t yet indicating that it is time for additional stimulus (0.5 is the threshold). But then the market doesn’t think the Fed should be cutting yet either. And when it is time for taking the foot off the brake, if I were an American taxpayer contemplating huge debt and deficits, I think I’d prefer to see the Fed do the stabilisation action.

But much the biggest issue is that inflation line in the rule. I’ve not seen anything similar in her US proposal. The general idea is that if (core) inflation is high you really don’t want to be adding automatic stimulus to the fire (any more than discretionary bits, like the “cost of living payments”). As Dom Stephens pointed out, there is an argument the restriction isn’t tough enough even as Sahm expressed it: after all the Reserve Bank is supposed to be aiming at 2 per cent, and if inflation is above target overall macro policy is still supposed to be bearing down on inflation (although here I would note the lags, and if macro policy isn’t adjusted until inflation is all the way back to target midpoint it is almost certainly rather too late). But lets stick with Sahm’s version.

She presented this chart (Treasury sent out her presentation to attendees but hasn’t yet put it on their general website)…

Click to view

…and claps herself on the back. Her fitted rule, she claims, triggers in all the recessions except the 1997/98 one (which had as much to do with drought and bad domestic monetary policy as Asia). Unfortunately, I think she has been misled by some of her data, and doesn’t have any real domestic context. As a starter, from the bottom half of her table (“technical recession”) the 1989 sharp fall in consumption was from a base quarter immediately prior to an increase in GST, so at very least you’d need to adjust the rule for such (easily observable) events.

But what about the real recessions (top half of the table)? There is some ambiguity about the 87/88 event as her table says N to automatic payments but her text seems to say yes. But either way, there is absolutely no way that macro policymakers in early 1988 would have been wanting to add fiscal stimulus (automatic or otherwise). Inflation (headline and core concepts) was coming down but was far too high (for the Bank and for ministers), and every single one of the regular Reserve Bank reports in those days called for more fiscal consolidation to ease the pressure on monetary policy and the real exchange rate. Same goes for the 1991 recession. We were still trying to drive down inflation (it was too high relative to the new official target) and fiscal policy was all in a flurry by the averted threat of a double credit rating downgrade. Aggressive fiscal consolidation was the order of the day, both for fiscal reasons (primarily) but also to ease pressure on monetary policy),

Skip over 97/98 for the moment and we come to 2008/09. The sectoral model of core inflation – probably the best retrospective indicator of core trends – was well above 3 per cent all through 2008 and into 2009, so although I’m not sure what core measure Sahm is using in the table, inflation certainly wasn’t anything like acceptable to the Bank in the early days of the recession (Sahm’s focus). It was a year of fiscal expansion……but mostly because (a) Treasury misjudged the permanence of the high levels of government revenue at the peak of the boom, and (b) it was election year and the government was losing (and presumably preferred specific own-brand giveaways to mechanised ones). Even had the rule been in place, it probably wouldn’t have triggered before final Budget decisions were being made in April and early May 2008.

As for Covid, if I was trying to design an automated rule I’d just take the Covid period out of my sample. The (discretionary) wage subsidy – which might have been too generous, but did its job – was put in place in late March 2020, months before the Q1 consumption data were available. Not only would the rule have been far too late to trigger, but in the specific circumstances it would have been too small to be relevant (swamped by the size of the wage subsidy). And, as it turned out, the last thing that was needed in 2020 was more encouragement to people to spend…..when the overall policy response helped generate the worst breakout in inflation for decades.

She calls the current episode a “technical recession”, but the unemployment rate has risen already by more than a full percentage point and per capita GDP is down as much as it was in 2008/09 (and consumer spending has been very weak). So it feels like another downturn when the rule triggered but payments would not sensibly have been made because…..inflation.

It was Dominick Stephens who pointed out recessions are sometimes the solution (to inflation) not the problem to be resisted. And I think that does mark our experience out at least somewhat from the US – notably we went into the severe 2008/09 recession with a pre-existing inflation problem, and they did not.

So, curiously, what we are left with is that I can think of only one episode in the last 37 years (the data sample) when triggering the rule and making payouts might have been helpful (and I stress “might” because she isn’t modelling responses, or comparing alternatives), and that is the one of her real recessions where payments would not in fact have been made: the 1997/98 episode. Which seems a bit awkward for the proposal.

And that is before we start on the other problems with the scheme.

For example, if one could identify a new and reliable rule – for indicating that the economy was probably in recession – why not just (a) advertise it widely, and (b) pass it on with a strong commendation to the central bank MPC. If it is a great and reliable rule (a) the Bank would be likely to use it in some form or other, and (b) the markets and the public would recognise that conditions were likely to ease, and respond accordingly. And to turn things on their heads, if there is a preloaded fiscal response, doesn’t that make it more likely that the central bank will be even slower than usual (this isn’t personal to the RB, central banks generally tend to be too late) to react, relying in part on the coming fiscal hit to buy them a bit more time to wait and see? A realistic assessment of such a policy proposal would need to make allowance for those sorts of interactions.

And then there is politics. Why would any political party or coalition want to preload lump sum handouts, rather than (a) look to the RB to do its job, and (b) keep the fiscal fuel for its own spending or tax cutting priorities (and perhaps again this is a difference to the US: here the government automatically (by construction, having supply) has a majority for its own budget plans? And why would much of the public think that big handouts to beneficiaries, high school kids, the retired etc would be a great idea at a point in the cycle where – again by construction – the unemployment rate is perhaps only a little off cyclical lows – and some of those lows (as recently) may have been quite extremely low. (This is, incidentally, one of the conceptual problems with the rule – which is just based on empirical regularities. Unemployment rates do drop below sustainable levels, well below at times. There is no good reason to think that additional policy stimulus is required just because the unemployment is finally heading back towards some sort of NAIRU.)

Monetary policy isn’t perfect. Our central bank these days is certainly anything but. But the case for looking beyond monetary policy for cyclical stabilisation just hasn’t really been made convincingly, and – particularly here in the New Zealand case – a simple automated rules looks to have been as unfit for purpose as was the idea (touted a bit in the US) of having the Fed mechanically implement a Taylor rule.

Oh, and then there was the profound asymmetry. There is nothing in this sort of rule – or even a readily conceivable alternative one – that could credibly operate on the other side of the cyclical; pulling money out of the system according to some rule. It really is easier to give money away than to take it back. Much better to keep fiscal policy doing what it does best, and leave cyclical stabilisation efforts to the central bank (a case that, admittedly, would be more compelling in New Zealand were the central bank and its key public faces not so egregiously bad, and unwilling ever to admit or learn from inevitable errors).

But, as I say, I found it useful to think hard about Sahm-type rules in the specific context of New Zealand and its experiences in recent decades.

PS. Finally, I thought I’d take a look at the US Sahm rule indicator. It isn’t yet indicating that it is time for additional stimulus (0.5 is the threshold). But then the market doesn’t think the Fed should be cutting yet either. And when it is time for taking the foot off the brake, if I were an American taxpayer contemplating huge debt and deficits, I think I’d prefer to see the Fed do the stabilisation action.

Click to view

PPS Sahm did not that a tool like this might be more useful when monetary policy was constrained (ie at a lower bound). But since there are ready technical solutions to lower bound issues – that don’t cost taxpayers billions of dollars – perhaps it would be better for central banks (chivvied along by Treasurys if necessary) to final fix the lower bound issues and leave monetary policy free to do its job, imperfectly (in the nature of human institutions).

UPDATE 13/6 Thinking a little more about Sahm rule types of proposal, they seem best suited to a world in which the economy is routinely running at or around capacity and then a demand-shock recession arises out of the blue (and thus an increase, even a modest one, in the unemployment rate might reasonably indicate a case for policy stimulus). But that isn’t often the case (probably generally, but certainly not in New Zealand in recent decades). As just one example, around two thirds of OECD countries had their lowest unemployment rates in the period 1995 to 2007 in 2007 itself, often in the December quarter, the very eve of the recession getting underway.

Michael Reddell spent most of his career at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, where he was heavily involved with monetary policy formulation, and in financial markets and financial regulatory policy, serving for a time as Head of Financial Markets. Michael blogs at Croaking Cassandra - where this article was sourced.

1 comment:

This woman's ideas sound like a 1930s answers to a 2020s problems.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.