Rewriting History: The truth about slavery and the British Empire

You’d think from the way some people talk that the British Empire invented slavery, ran it single-handedly, and then quietly slunk away in shame. That’s the cartoon version of history pushed by activists who want every discussion of colonisation to be a morality play with Britain cast as the eternal villain. But here’s the truth they don’t want to admit: slavery has existed in every civilisation in recorded history. The British Empire’s part in it was ugly, but small compared to the vast, bloody scale of human bondage across the world and throughout history. And Britain, unlike most of the civilisations before and after it, actually ended slavery at home and in its empire.

The real story is not one of uniquely British evil, but of a human horror as old as time and of the first major power in history to use its global dominance to end it. The uncomfortable reality is that the loudest voices today only tell the first half of the story. They leave out the abolition acts, the Royal Navy hunting slave ships, the treaties, the military interventions, and the fact that other parts of the world, particularly in the Islamic world, clung to slavery long after Britain had stamped it out. This isn’t just bad history. It’s deliberate misinformation.

The anti-colonisation narrative has become deeply ingrained. The obsession with recasting Britain as the ultimate villain has led to a selective rewriting of history, one that ignores both the global scale of slavery and Britain’s leading role in abolishing it.

This distortion has been turbo-charged by decades of ideological activism, identity politics, and institutional capture. In the rush to frame colonial history as a one-dimensional tale of wicked Europeans and ‘Noble Savages’, nuance has been bulldozed. The British Empire’s part in the transatlantic slave trade is now presented in isolation, stripped of the wider global context and scrubbed of Britain’s unparalleled record as an abolitionist superpower. School curriculums, museum exhibits, and Netflix docudramas often stop the timeline in the early 19th century, freezing Britain in the role of slaver while conveniently airbrushing out what came next.

Why? Because anti-Western and especially anti-British sentiment thrives on slogans, not facts. By exaggerating Britain’s role as a perpetrator while erasing its leadership in abolition, activists get to reinforce a worldview that casts the West as uniquely immoral and irredeemable. Narratives of colonisation are now often less about rigorous historical inquiry and more about present-day political leverage. It’s not an accident; it’s a political tool. But the cost is high: we end up with a dishonest public understanding of history, we cheapen the true horror of slavery by ignoring its global scale, and we erase one of the most remarkable stories in human history: how Britain, once a participant, became slavery’s fiercest opponent.

Long before the first British ship reached Africa, ancient Egypt was using mass slave labour to build its monuments. The Roman Empire ran on slavery, with conquered peoples sold and worked to death. Vikings raided across Europe, capturing men, women, and children to serve in their settlements. The Ottoman Empire operated vast slave markets, trafficking millions. And here in the Pacific, slavery existed long before Europeans arrived; in Māori society, taurekareka (slaves) were often war captives, forced into servitude and sometimes killed for ritual or eaten as part of utu (revenge).

The anti-colonisation narrative has become deeply ingrained. The obsession with recasting Britain as the ultimate villain has led to a selective rewriting of history, one that ignores both the global scale of slavery and Britain’s leading role in abolishing it.

This distortion has been turbo-charged by decades of ideological activism, identity politics, and institutional capture. In the rush to frame colonial history as a one-dimensional tale of wicked Europeans and ‘Noble Savages’, nuance has been bulldozed. The British Empire’s part in the transatlantic slave trade is now presented in isolation, stripped of the wider global context and scrubbed of Britain’s unparalleled record as an abolitionist superpower. School curriculums, museum exhibits, and Netflix docudramas often stop the timeline in the early 19th century, freezing Britain in the role of slaver while conveniently airbrushing out what came next.

Why? Because anti-Western and especially anti-British sentiment thrives on slogans, not facts. By exaggerating Britain’s role as a perpetrator while erasing its leadership in abolition, activists get to reinforce a worldview that casts the West as uniquely immoral and irredeemable. Narratives of colonisation are now often less about rigorous historical inquiry and more about present-day political leverage. It’s not an accident; it’s a political tool. But the cost is high: we end up with a dishonest public understanding of history, we cheapen the true horror of slavery by ignoring its global scale, and we erase one of the most remarkable stories in human history: how Britain, once a participant, became slavery’s fiercest opponent.

Long before the first British ship reached Africa, ancient Egypt was using mass slave labour to build its monuments. The Roman Empire ran on slavery, with conquered peoples sold and worked to death. Vikings raided across Europe, capturing men, women, and children to serve in their settlements. The Ottoman Empire operated vast slave markets, trafficking millions. And here in the Pacific, slavery existed long before Europeans arrived; in Māori society, taurekareka (slaves) were often war captives, forced into servitude and sometimes killed for ritual or eaten as part of utu (revenge).

by Louis Auguste de Sainson, 1839. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

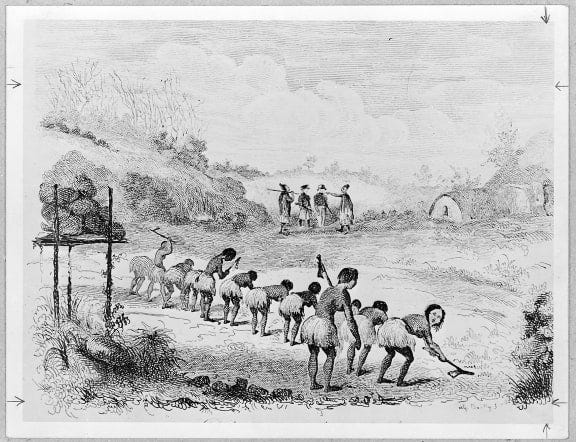

The transatlantic slave trade was horrific. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, 12–15 million Africans were trafficked to the Americas in appalling and inhumane conditions. Britain played a major part, especially in the 18th century. But the Arab slave trade, which predated the Atlantic one by centuries, took at least as many people, if not more, from Africa, often castrating men and forcing women into harems. The Indian Ocean slave trade moved millions from Africa and Asia to the Middle East, Persia, and beyond. And slavery was widespread within Africa itself, with African rulers and traders capturing and selling people to both Europeans and Arabs. The Atlantic trade was appalling, but it was not unique, and it was not the largest or longest-running in history.

The abolition of slavery in the British Empire wasn’t an accident of history, it was the result of decades of relentless campaigning, political manoeuvring, and sheer moral courage from a cast of extraordinary figures. At the centre of it all was William Wilberforce, the evangelical Member of Parliament who became the face of the abolitionist movement. For more than twenty years, Wilberforce introduced bills to end the slave trade, facing defeat after defeat as the wealthy trader lobby and entrenched economic interests dug in their heels. His persistence, rooted in deep religious conviction, eventually paid off with the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807.

The transatlantic slave trade was horrific. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, 12–15 million Africans were trafficked to the Americas in appalling and inhumane conditions. Britain played a major part, especially in the 18th century. But the Arab slave trade, which predated the Atlantic one by centuries, took at least as many people, if not more, from Africa, often castrating men and forcing women into harems. The Indian Ocean slave trade moved millions from Africa and Asia to the Middle East, Persia, and beyond. And slavery was widespread within Africa itself, with African rulers and traders capturing and selling people to both Europeans and Arabs. The Atlantic trade was appalling, but it was not unique, and it was not the largest or longest-running in history.

The abolition of slavery in the British Empire wasn’t an accident of history, it was the result of decades of relentless campaigning, political manoeuvring, and sheer moral courage from a cast of extraordinary figures. At the centre of it all was William Wilberforce, the evangelical Member of Parliament who became the face of the abolitionist movement. For more than twenty years, Wilberforce introduced bills to end the slave trade, facing defeat after defeat as the wealthy trader lobby and entrenched economic interests dug in their heels. His persistence, rooted in deep religious conviction, eventually paid off with the passing of the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act in 1807.

William Wilberforce

Wilberforce wasn’t alone. Thomas Clarkson, less famous today but equally crucial, devoted his life to gathering evidence of the brutality of the trade. He interviewed sailors, collected shackles and branding irons, and compiled meticulous records that exposed the inhumanity of slavery to the British public and Parliament alike. There was no other way for people to even imagine the atrocities happening elsewhere in the world. There was no X or TikTok to broadcast events live. Clarkson was the researcher, Wilberforce the orator and, together, they made the case against slavery impossible to ignore. Alongside them was Granville Sharp, a legal mind who took up landmark cases such as that of James Somerset, the enslaved African man whose 1772 court ruling effectively made slavery unenforceable in England. These men formed the backbone of what was known as the “Clapham Sect,” a group of evangelical Anglicans who turned their faith into political activism.

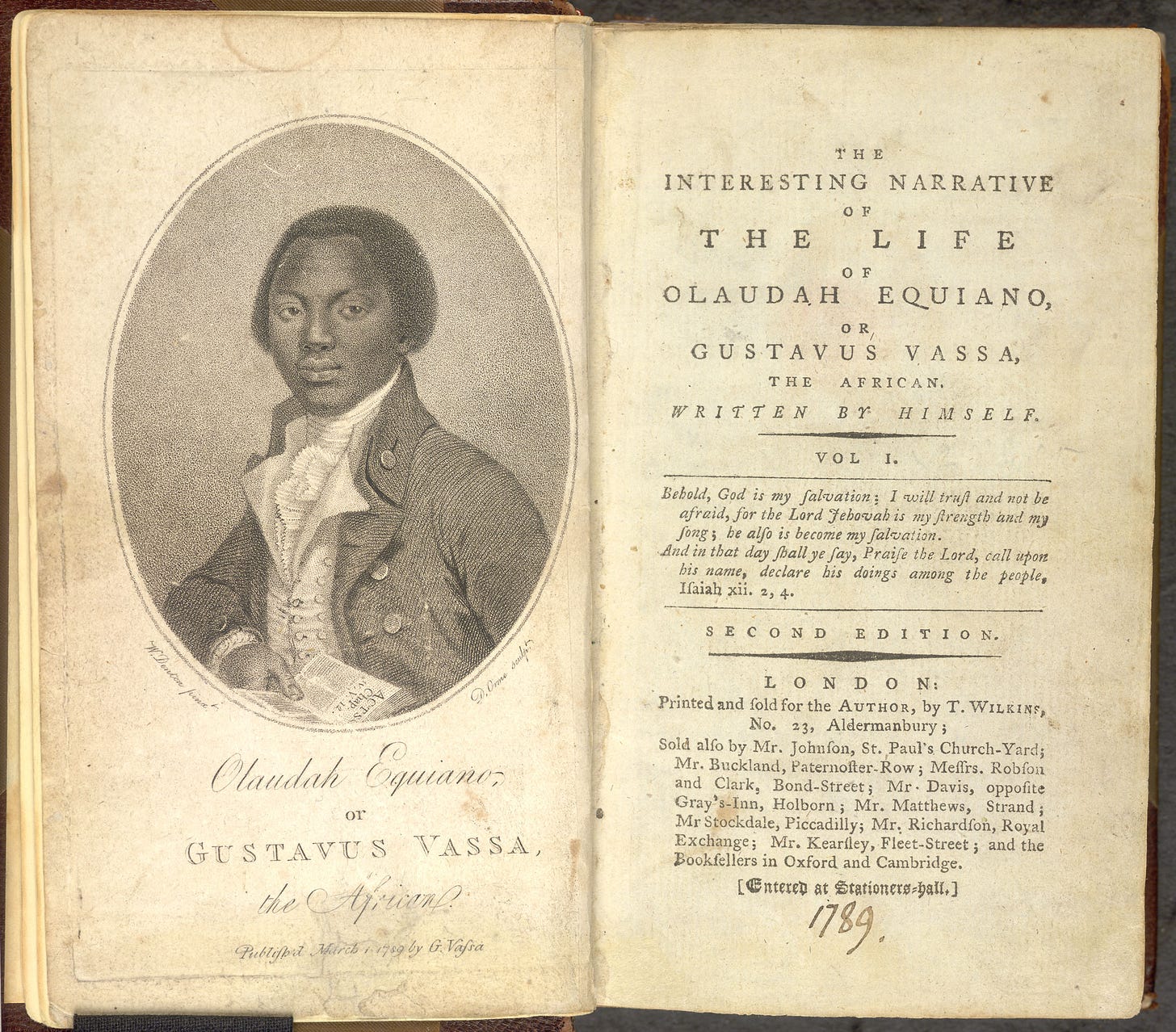

Then there were the voices of the formerly enslaved themselves, whose testimony gave abolitionists the moral authority they needed. Olaudah Equiano, kidnapped from Africa as a child and sold into slavery before buying his own freedom, published his memoir in 1789. His powerful account of life as a slave shocked the conscience of Britain and gave a human face to the statistics. Others, such as Ignatius Sancho, also wrote and spoke publicly, defying stereotypes and demonstrating the humanity denied to those in bondage.

By 1833, the Slavery Abolition Act had freed over 800,000 enslaved people across the Empire. This wasn’t simply a matter of cleaning up Britain’s own house; it marked the start of a century-long global campaign to stamp slavery out elsewhere.

After abolition at home, new figures carried the torch abroad. Lord Castlereagh, as Foreign Secretary, negotiated anti-slavery treaties at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, pressing other European powers to curb their involvement. Later, Lord Palmerston and other foreign secretaries used Britain’s diplomatic and naval power to bully reluctant nations like Brazil, Spain, and Portugal into giving up the trade. On the high seas, naval officers such as Commodore Sir George Collier and Admiral Sir Charles Hotham led the West Africa Squadron, intercepting slave ships in treacherous conditions. Between 1808 and 1860, they captured over 1,600 ships and liberated more than 150,000 Africans.

Taken together, these efforts show that Britain’s abolition of slavery was not a token gesture but a national and international crusade. It was spearheaded by campaigners, politicians, writers, freed slaves, lawyers, and sailors; a coalition that turned moral conviction into global action. It is one of the few times in history when an empire used its immense power not to expand oppression, but to fight an entrenched evil beyond its own borders.

Britain’s abolition of slavery was not just a moral turning point, it was one of the most expensive public policy decisions in history. When Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, the law didn’t just liberate the enslaved; it also compensated slave owners for their “loss of property.” This compensation package was enormous for the time: £20 million. To put that in perspective, it amounted to roughly 40% of the government’s annual expenditure; an extraordinary financial commitment for any nation.

Click to view

Compensating slave owners was, on its face, a grotesque moral compromise effectively rewarding those who had profited from human misery. It was a bitter pill for abolitionists to swallow, but in the political reality of the 1830s, it was the price of securing the votes needed to pass the law. The alternative was to let the system drag on for decades while vested interests blocked reform. By paying off the owners, Britain dismantled slavery in its empire in one decisive stroke, rather than in slow, piecemeal reforms that would have condemned countless more people to bondage. In hindsight, abolition at any cost was the right call: no sum of money could outweigh the moral imperative of ending a crime against humanity.

Only a small percentage of Brits ever actually owned slaves, and almost all of them were members of the elite. The vast majority of the population had no direct stake in slavery whatsoever. Yet every taxpayer, from dock workers in Liverpool to coal miners in Wales, was on the hook for the bill. The government didn’t have the cash upfront to pay off the slaveowners, so it borrowed the money; a debt so large that British taxpayers were still paying it off well into the 21st century. In fact, the final instalment wasn’t cleared until 2015.

This meant that generations of Brits, including the descendants of people who had nothing to do with slavery, paid for the moral decision to end it. It’s a fact that never fits neatly into the anti-Britain activist narrative. It tells a story not of a nation clinging to slavery, but of one willing to shoulder a massive collective financial burden to stamp it out. In the history of abolition, this was unprecedented. A society-wide investment in ending an entrenched evil, paid for by people who never profited from it in the first place.

Despite Britain’s leadership, much of the world dragged its feet. Slavery persisted for decades, and in some cases, more than a century, after Britain had abolished it. Brazil didn’t end slavery until 1888. Saudi Arabia and Yemen held out until 1962. Qatar didn’t abolish it until 1952. Mauritania clung to the practice until 1981, and reports suggest that slavery-like practices still occur there illegally today. The uncomfortable truth for modern activists is that the slowest states to abolish slavery were overwhelmingly in the Islamic world, the same regions where slavery had been entrenched long before the Atlantic Slave Trade.

Slavery was a core institution in Islamic empires, from the Abbasids to the Ottomans. Millions of sub-Saharan Africans and Eastern European Christians were captured and sold in North Africa and the Middle East, and eunuchs were a prized commodity in elite courts. While the Atlantic slave trade ended in the 19th century, slavery in parts of the Middle East continued openly into the 20th and in some places, continues in illegal forms today.

Modern slavery in Libya is one of the most chilling reminders that this evil is far from a relic of the past. Since the collapse of Muammar Gaddafi’s regime in 2011 and the ensuing chaos, Libya has become a hub for human trafficking, particularly of sub-Saharan African migrants trying to reach Europe. Many are kidnapped, sold at open-air slave markets, and forced into hard labour, domestic servitude, or sexual exploitation.

Footage from 2017 showed young men being auctioned off for as little as $400, sparking international outrage, but little real action. For all the moral posturing in the West about “historic slavery,” the fact that human beings are still being bought and sold in Libya today ought to be front-page news, yet it barely registers in the activist narratives obsessed with 18th-century Britain.

Sex trafficking is one of the most pervasive forms of modern slavery, trapping millions of predominately women and children in a cycle of exploitation. Victims are coerced, deceived, or outright abducted and then forced into prostitution or sexual servitude, often under threat of violence to themselves or their families. The trade is global, operating in both the shadows of organised crime and the daylight of supposedly “legitimate” industries. Like historical slavery, it reduces human beings to commodities, bodies to be used, sold, and discarded. Yet unlike the long-abolished legal slave trades, sex trafficking thrives today in plain sight, fuelled by corruption, demand, and the failure of governments and international bodies to confront it with the same determination once shown in the fight against the transatlantic slave trade. But this is a whole other Substack that I will likely write in the future!

When activists portray slavery as a uniquely British crime, they are not “correcting history”, they are distorting it. They erase the global scale of human bondage, ignore the fact that Britain led the charge to end it, and feed a one-sided narrative that fuels anti-British, anti-Western sentiment. Yes, Britain participated in the Atlantic slave trade, and yes, that was wrong. But Britain was also the world’s most powerful abolitionist force, a fact worth acknowledging if we want an honest conversation about history.

Calls for reparations from Britain for its role in the Atlantic slave trade are not just historically ignorant, they are a shameless cash grab dressed up as moral virtue. Clueless politicians in the United States, who clearly haven’t cracked a history book since high school, parrot these demands as if Britain simply walked away from slavery with a tidy profit. For grifting activists and opportunistic politicians to demand a “payout” is nothing more than an insult to history and a transparent attempt to turn a centuries-old moral victory into a modern-day grift.

History deserves honesty, not propaganda. Britain’s legacy on slavery is neither spotless nor singularly wicked. It is complex, human, and extraordinary. To remember only the chains and forget the courage, to dwell only on the crimes and not the costly crusade to end them, is to flatten history into caricature. The truth is that the British Empire stands out not because it practised slavery, it did, as others did before and after, but because it made the unprecedented choice to spend blood, resources, and decades of relentless effort to destroy it. That is not a story of shame to bury, but a story of moral leadership to tell in full. If we want to understand slavery honestly, we must look at the whole picture: the global scale, the British role in ending it, and the uncomfortable reality that this fight is far from finished today.

Why I wrote this piece

I primarily wrote this because I was triggered one too many times by people confidently espousing utter fiction about the history of the British Empire. In New Zealand we have a terrible problem of lack of historical knowledge and recent political narratives have popularised ideas of our history that simply have no evidence to back them up.

A long time ago now, when I was at the University of Auckland, I studied history and English. Yes, I have a BA (I returned to study some years later to do marketing). Anyway, my undergraduate degree was made up primarily of papers relating to colonisation, post-colonialism, and the histories and stories of marginalised people. What does that mean? It means I took a great interest in the stories of people(s) who traditionally had not been the writers of history. I studied the histories of women, the working classes, indigenous populations, and even the history of sex and sexualities. I similarly focused on these topics in my English papers (alongside a healthy serving of Shakespeare and one ill-advised Chaucer paper). Anyway! Graduating did not mark the end of my interest in stories and histories. I have continued to read and write a great deal about colonisation, marginalisation, empire, and the clashes of populations.

The thing about history that gets forgotten, and is perhaps why I find myself so often fruitlessly trying to set records straight, is that there is no single entirely correct narrative. Looking back requires a piecing together of perspectives supported by primary and secondary sources. It is, of course, written by the victors and so unearthing the stories of others takes more work and is open to more interpretation. Reading history should not be an exercise in moral or ethical reinterpretation either. People are, and always have been, the sum of all their attributes and actions. We are usually neither totally good nor totally evil. Our motivations are not cartoonishly 2D and our drivers tend to be self-interested rather than outwardly destructive for the sake of it. Creating saints and devils of historical figures is usually an act of fictionalising them. I say “usually” because there are certainly a few characters who have been so singularly awful that perhaps they are the rare case of true evil. I don’t think it is necessary for me to name names.

I wish more people understood that our historical heroes will also have done things that we now deem unacceptable. They may have even done things that would have been unacceptable at the time. Winston Churchill was, in my view, one of the greatest men to ever live, but he was also deeply flawed, for example. Even Martin Luther King Junior was a philandering scumbag who regularly cheated on his wife! Find me a hero and I will find you a flaw.

This is true also of civilisations and empires. None are without the stain of war and conquest. No group of people can look back at their ancestry and find hands clean of blood. We are all children of the conquerers or the survivors; mostly a mix of both.

In writing this brief glimpse at history, I hope that my readers will get a taste of my interpretation of history as a tapestry of human failure and victory; moral and material. The British Empire was definitely responsible for human suffering and we should reflect on that, but it was also responsible for huge advancements in technology, exploration, and morality. New Zealanders are entitled to a better understanding of our place in history than current discourses allow. The ‘British = bad’ and ‘Māori = good’ schtick is reductive and flattens the nuances of our stories; the very things that make learning about the past so interesting.

************************

Ani O'Brien comes from a digital marketing background, she has been heavily involved in women's rights advocacy and is a founding council member of the Free Speech Union. This article was originally published on Ani's Substack Site and is published here with kind permission.

8 comments:

Let's not forget that throughout the whole history of slavery, with all its inhumanity, the most brutal and inhuman of all was Maori slavery. We should also remember that it was colonization that stopped it. But we're not allowed to even think about that because that would be challenging the narrative of the perfect Maori society and the evil colonialists.

Well said Ani.

It intrigues me that we profess such abhorrence for slavery iyet have no problem with the unbelievably low prices of manufactured goods from developing countriess. A miniscule fractionn of what would cost to make locally and that with wages claimed to be low..

A most interesting and thought-provoking piece. Thankyou.

One of the best pieces that I have ever read on slavery.

It should be a compulsory topic in our secondary schools, with an emphasis on Maori slavery of both their enemies, and unfortunate whites, right up until the moment the Treaty was signed.

Thank you Ani for an enduring article.

Congratulations Ani on your article . It was no mean feat getting rid of slavery as the Clapham group did, of Wesleyian belief . I don't believe for one minute without their Christian faith , they could have achieved what they did. It was such a prevalent and tremendous evil.

Slavery was the reason that A lot of Eastern European people are known as "Slavic". Very informative article Ani. Thankyou

One can read Eltis, Atlantic Cataclysm, which puts the British slave trade in broad global perspective. Summaries of the book on the web.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.