There’s been a lot of noise this week about the Government’s plan to tighten access to the Jobseeker benefit for 18 and 19-year-olds. Depending on which paper you read, it’s either “a cruel attack on youth” or “a long-overdue dose of common sense.” Let’s strip it down to what’s actually being proposed, who’s saying what, and where the real risks and benefits lie.

Most New Zealanders would probably agree that when an 18 or 19-year-old is trying to find their feet, their parents should be the first port of call, not the taxpayer. It’s the way most families operate already. Mum and dad help out for a while, whether that’s with rent, groceries, or living rent-free while their kid figures things out. In fact, most Kiwis aged 18-19 are still living at home with parents these days. Where opinion starts to fracture is over how far that principle should stretch when it’s written into law.

This debate is really an argument in two parts. The first is philosophical: what role should the state play in supporting young adults when their families are capable of doing so? That’s a question about fairness, between taxpayers and families, between independence and dependency. The second is practical: when is it appropriate for the state to step in, and to what degree? That’s where things get messy. Life isn’t neat, families aren’t uniform, and sometimes “capable” on paper looks very different in real life. It’s in that grey area, between principle and practice, that the Government’s new Jobseeker rules for 18 and 19-year-olds sit.

From November 2026, 18 and 19-year-olds applying for Jobseeker Support (or the Emergency Benefit) will need to pass a parental income test or show they can’t rely on their parents.

This debate is really an argument in two parts. The first is philosophical: what role should the state play in supporting young adults when their families are capable of doing so? That’s a question about fairness, between taxpayers and families, between independence and dependency. The second is practical: when is it appropriate for the state to step in, and to what degree? That’s where things get messy. Life isn’t neat, families aren’t uniform, and sometimes “capable” on paper looks very different in real life. It’s in that grey area, between principle and practice, that the Government’s new Jobseeker rules for 18 and 19-year-olds sit.

From November 2026, 18 and 19-year-olds applying for Jobseeker Support (or the Emergency Benefit) will need to pass a parental income test or show they can’t rely on their parents.

Photo / Mark Mitchell

If their parents earn less than $65,529 a year (before tax), they’ll still be eligible. If they earn more than that, the expectation is that parents will support their children instead of the taxpayer, unless they can show a “parental support gap” due to estrangement, safety issues, or similar.

The Government estimates about 4,300 young people will lose eligibility under the new rules, with roughly 4,700 remaining eligible.

There’s also a $1,000 “job retention” bonus for young people who find work through MSD and stay off a benefit for a year. The Government says this is about shifting expectations: “if you can work or train, you should.”

Ministers argue this isn’t about punishment; it’s about responsibility. They say too many school-leavers are drifting straight onto welfare and getting stuck there. If their parents can help, they should, and if they can’t, the state should then step in. It’s framed as a “family first, welfare second” approach designed to prevent long-term dependence. The policy sits neatly alongside National’s broader “back-to-work” narrative and is part of a push to get 50,000 more people off benefits by 2028.

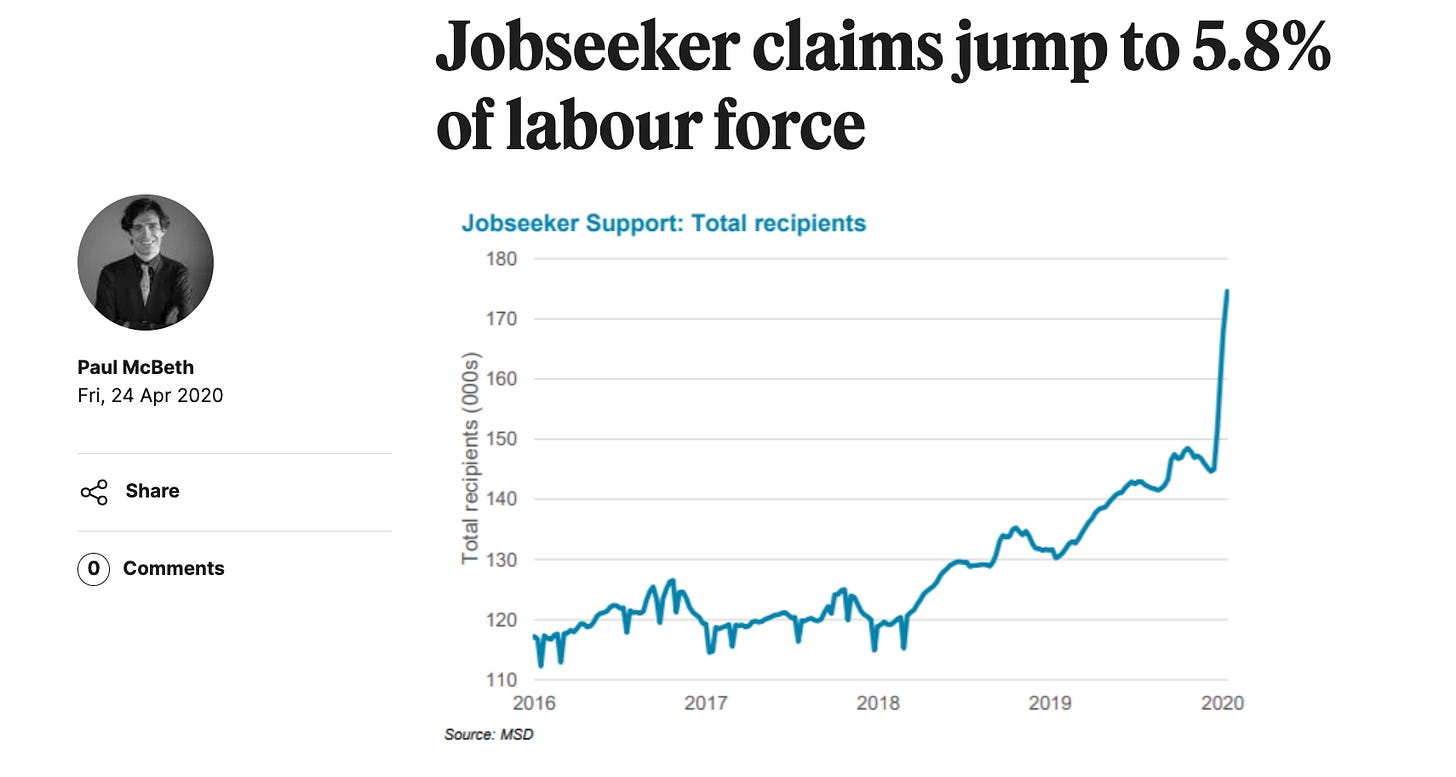

The Government has been quick to justify the change by pointing to Labour’s dismal welfare record. The number of people on benefits ballooned under their watch, even during periods of historically low unemployment. The jobs were there, but the incentives were broken. National’s case is that this reform isn’t about penny-pinching, it’s about resetting expectations after years of drift. They’ve also been citing a particularly sobering figure that young people who go on a benefit before the age of 20 stay on welfare for an average of 17 years. It’s that long tail of dependency the Government says it’s determined to break.

One of the more controversial aspects of this policy is that it doesn’t just affect unemployed school-leavers, it also captures some young people with temporary health conditions or disabilities who are on the Jobseeker benefit rather than the Supported Living Payment. That’s raised alarm bells among disability advocates, who point out that not all disabilities are permanent and many young people move in and out of work or study depending on their health. Under the new rules, if their parents earn above the $65,529 threshold, these 18–19-year-olds could be denied income support altogether, even while they’re medically unfit for work. Of course, the argument is that in the first instance support for temporarily unwell family members should be from family, not taxpayers.

On the other side of the House, Labour has framed the changes as punitive, tone-deaf, and fundamentally unfair. Their argument is that the policy blames young people for economic conditions they didn’t create, in a labour market where entry-level jobs are drying up, the cost of living is high, and even full-time work can’t guarantee financial independence. Labour MPs have repeatedly emphasised that not every family earning $65,000 is sitting comfortably; many of those households are already stretched thin by mortgages, food costs, and fuel prices.

Click to view - Business desk article from 2020.

They argue that the Government is mistaking poverty for laziness. That rather than offering pathways into training, apprenticeships, or meaningful employment, it’s simply pulling the rug out from under thousands of young people who will now be left without income. The Government’s retort is that they are doing those things as well.

Labour has also warned that the new rules could exacerbate youth homelessness, force more teenagers into unsafe living situations, and undermine the very social cohesion the Government claims to value. In their view, the focus should be on creating job opportunities and investing in wraparound support, not tightening the screws on those who are already struggling to get a foothold in adult life.

The Greens have taken an even harder line, describing the policy as “cruel and counterproductive”. Social development spokesperson Ricardo Menéndez March has argued that it will “push more young people into poverty”, particularly those with unreliable, neglectful, or unsafe home lives who will now face additional bureaucratic barriers just to survive. In the Greens’ view, the reform reflects a deeply moralising attitude toward poverty, one that assumes young people on a benefit are choosing not to work, rather than recognising the structural and personal barriers that often keep them out of employment.

They’ve also pointed out that the $65,529 threshold sits barely above the median household income for many families already struggling with the cost of living, making it a blunt and unrealistic measure of a family’s capacity to support another adult. The Greens see the change as part of a broader ideological pattern: a Government that prefers punishment over compassion and welfare cuts over social investment.

Te Pāti Māori has been scathing, framing the policy as “yet another” example of the Government “punching down on rangatahi Māori” while protecting privilege at the top. Co-leaders Rawiri Waititi and Debbie Ngarewa-Packer have argued that the change disproportionately targets young Māori, who are already overrepresented in benefit statistics due to systemic disadvantage, intergenerational poverty, and the lingering effects of colonisation on education and employment pathways.

They see the parental income test as a middle-class policy written for Pākehā families, one that assumes stable homes, two incomes, and a willingness or ability for parents to provide. In reality, Te Pāti Māori argues, many Māori whānau are already stretched supporting wider family networks, and this policy will simply shift costs from the state onto households least able to bear them. The party has linked the reform to what it calls a broader “war on the poor,” citing welfare sanctions, the removal of free lunches (which has not actually happened), and the scaling back of community programmes as evidence that the Government is punishing poverty instead of addressing it. In their view, it’s not just bad economics, it’s a breach of the Crown’s obligation to care for all citizens, especially the young and vulnerable.

From the Government’s perspective, the backlash from Labour, the Greens, and Te Pāti Māori is predictable opposition theatre; long on emotion, short on solutions. Ministers argue that Labour’s record speaks for itself: during six years in power, the number of working-age New Zealanders on benefits grew even while unemployment hit record lows. To the Government, that’s proof that Labour’s “kindness-first” welfare settings bred dependency, not opportunity. The message from National, ACT, and New Zealand First is clear: if you’re young, healthy, and capable, the state’s role is to help you into work or study, not pay you to stay home. The policy isn’t about cruelty; it’s about reversing a culture of complacency that saw too many young people become trapped in the welfare system.

To Labour’s claim that $65,000 isn’t enough for a family to support another adult, the Government would respond that most New Zealand parents already do, often without complaint, and without the need for a government top-up. Ministers point out that the policy doesn’t expect struggling families to bankroll their kids, only those with the means and stability to do so. For the rest, the parental support gap test exists precisely to protect young people in unsafe or unsupportive environments. In the Government’s view, this safeguard undermines the opposition’s argument that the policy will leave vulnerable teens destitute. Those with genuine need will still receive help.

As for the Greens’ outrage, the Government would say it’s a familiar case of ideological blindness. Ministers argue that the Greens’ vision of endless welfare entitlements is unsustainable and does nothing to address intergenerational poverty. Giving young people cash with no strings attached, they say, simply locks them into dependency earlier. Instead, this reform aims to connect 18 and 19-year-olds with real opportunities, education, apprenticeships, and jobs, backed by incentives like the $1,000 job retention bonus. From their standpoint, it’s the Greens’ refusal to impose expectations, not National’s policy, that keeps young people trapped at the bottom.

In response to Te Pāti Māori’s accusations, Government ministers would likely point to the universal design of the policy. It applies to everyone, regardless of ethnicity, and argue that raising expectations for Māori youth is not discrimination, it’s empowerment. They would highlight that many Māori leaders and employers have been calling for stronger pathways into trades, regional jobs, and training whish is exactly the kind of opportunities this policy is meant to encourage. Far from “punishing” Māori, the Government would claim it is investing in their potential by setting the same expectations of independence, resilience, and self-determination as for everyone else.

Ultimately, the Government’s argument boils down to the belief that welfare should be a safety net, not a lifestyle, and the state was never meant to replace parents and family when it comes to responsibility for fledgling adults. Ministers see this reform as a step toward restoring the idea that being in work is far better than being on welfare, that families have responsibilities before the state does, and that public money should be reserved for those who truly have nowhere else to turn.

Predictably, the narrative has split along ideological lines: economic efficiency vs. social harm, but in an interesting twist, while the Taxpayers’ Union supports the general idea that parents who can support their kids should do so, they’ve criticised the bluntness of the $65,529 cut-off. They argue that the threshold creates a “cliff effect” where a parent earning one dollar more suddenly disqualifies their child entirely. Their fix? A tapered approach where support gradually reduces rather than cutting off overnight.

The principle behind this reform isn’t radical. Families should help first when they can. The problem is in how that principle gets enforced.

Politically, this fits National’s “responsibility” narrative neatly, but it’s also one of those policies that will be judged in hindsight. If the result is more young people working or training, they’ll claim vindication. If it produces headlines about kids couch-surfing and being cut off, it’ll backfire fast. Either way, it’s a reminder that social policy is easiest to sell in theory and hardest to administer in practice.

This one’s a classic example of a good idea wrapped in untested design. Of course, we don’t want teenagers defaulting to welfare the moment they leave school. That’s a disaster for them and for the taxpayer. It’s entirely fair to expect families who can afford to help their kids to do so. But a family earning $65,530 a year before tax is hardly flush with cash.

The intention to push young people into work, training, or education is great, but the proof will be in the pudding. If the Government doesn’t address the threshold cliff and make sure genuine cases of estrangement and hardship are handled humanely, this will look less like “personal responsibility” and more like bureaucratic cruelty dressed up as tough love.

What are your thoughts? Fair? Unfair? Good policy? Bad?

Ani O'Brien comes from a digital marketing background, she has been heavily involved in women's rights advocacy and is a founding council member of the Free Speech Union. This article was originally published on Ani's Substack Site and is published here with kind permission.

4 comments:

How does he expect these young kiwis to compete in the job market with immigrants who are happy to work for less than minitwage for five years, until they get permanent residency.

Stopping the influx of cheap labour would be a fine start.

Ani, I have not read all of your long post, but I mostly agree with you. The part I find incredible is that the government does not just want to punish the lazy, but all the disabled and even those with cancer. I seldom agree with the Greens but I watched the crazy Mexican questioning Luxon, and the Mexican was right.

What "intrigues" me, is the comment made by "The Mexican Import" into NZ Politics.

On the basis of the comment - "push more young people into poverty", to me, is the "kettle calling the pot black", particularly since his 'import' comes from a Country that has always had a "poverty issue". To whit, why do (and have done so for many Years) - Mexican's migrate North across the Border into the US looking for and engaging in meaningful employment?

If it was not for American Companies setting up industrial business, in Mexico (examples motorcycle & car components),

that Country would have had and/or still have, major social issues with the Population. As far as I am aware there is not a Benefit system in Mexico for the unemployed and/or unemployable.

An interesting facet to NZ and employment, the "Hospo" industry has issues finding employees and if what was related to me recently, many of the 18- 20 year old's are " not interested, it is to much like hard work, and has long hours".

Do away with the minimum wage. That would need a major philosophical change of judging policy not by its worthy intentions but by its measurable outcomes, which would be an almost insurmountable mental challenge for most politicians and leftists.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.