Like most of the developed world, we in New Zealand live – we like to think – in a representative democracy. Rather than directly voting on issues, we vote for politicians who represent us in Parliament and in local councils. These politicians are responsive to our views, and if they’re not, we can kick them out at the next election and vote in another set of politicians who are.

That, at any rate, is the theory. As a number of recent studies from across the developed world have reminded us, though, politicians – even elected ones – tend to be very different to the voters they represent, especially in terms of their economic background and educational attainment. They also tend to be less ethnically diverse and more male. Most worrying of all for the theory of representative democracy, political elites also have very different beliefs and preferences than ordinary people.

Here in New Zealand, too, there is a disconnect between politicians and the people they represent.

In recent years, governments have enacted a number of policies that were clearly opposed by most Kiwis. ‘Three waters’ legislation was forced through despite multiple polls consistently showing that a majority of New Zealanders opposed it. Only a year after Three Strikes legislation was repealed, a poll suggested that nearly two thirds of New Zealanders wanted it to stay on the books (and only 16% wanted it repealed). And despite polls suggesting that clear majorities of Kiwis support the actual wording of the Treaty Principles Bill, it failed to progress beyond its second reading.

What’s the solution? More direct input from citizens. This, after all, is what democracy is supposed to be about. The ancient Greek word dēmokratia meant ‘rule by the people’ (the dēmos) and the first democratic states in the Greek world involved much more direct participation by citizens than our modern, representative systems.

In Athens, the largest and best-documented democracy, citizens voted directly on decisions facing the city in assemblies that met thirty or forty times a year. They could volunteer to be randomly allotted into service on the state council, as a city official, or as a juror in the city’s popular courts. They could even vote to hold an ‘ostracism,’ a kind of unpopularity contest in which the ‘winning’ politician would be exiled from Athens for ten years.

Nowadays, that last procedure might raise worries about human rights. And ostracism is just one feature of ancient Athenian democracy that we would probably not want to revive in the modern day. (Two others are slavery and the exclusion of women and virtually all immigrants from political participation.) But we are not alone in believing that the more direct democratic institutions of ancient Greece can help inspire and inform democratic innovation today.

In fact, academics and activists have been experimenting with direct democratic ideas for decades now. Participatory budgeting, in which local citizens take part in balancing the books in their municipality, has been tried out in over a hundred cities, mainly in Brazil. Direct votes on public issues through referenda have become increasingly common, not only in Switzerland (which has held nine or ten a year in recent decades), but also in California, where citizens can initiate referenda themselves, and in the United Kingdom, where three referenda (one of them legally binding) on major public issues have taken place in the last fifteen years.

The ancient democratic instrument which has been most enthusiastically explored in recent years, though, has been sortition (random allotment). James Fishkin started holding his ‘deliberative polls,’ which bring randomly-selected citizens together to discuss public issues, in the 1990s. Since then, randomly-selected ‘citizens’ assemblies’ have multiplied, with dozens taking place around the world just in the past few years. Organisations dedicated to the ideal of ‘deliberative democracy,’ like the UK-based Sortition Foundation, continue to disseminate citizens’ assemblies worldwide.

New Zealand currently has two main routes to plebiscites at the national level. The first route was opened up by the 1993 Citizens Initiated Referenda Act. This allowed citizens to trigger a non-binding referendum by presenting a petition signed by more than 10% of registered voters to Parliament within a year. This is the most democratic mechanism for triggering a referendum, as citizens get to choose the topic of the plebiscite themselves.

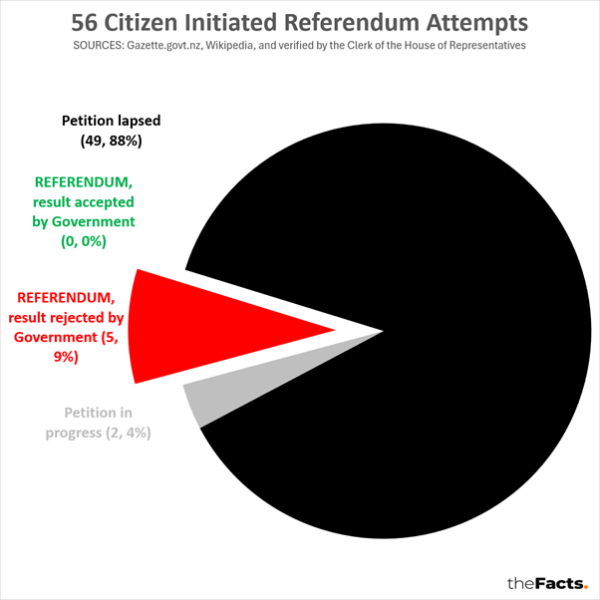

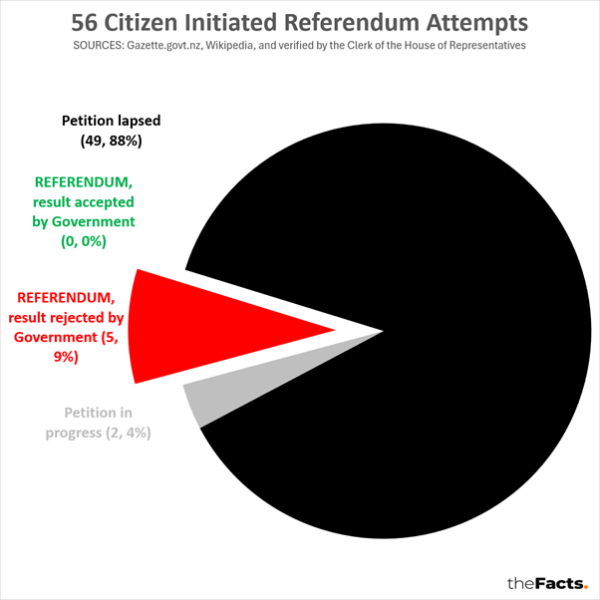

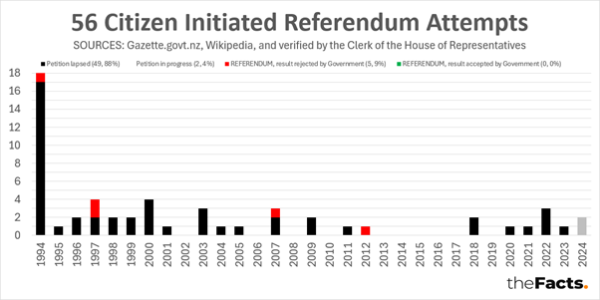

The results, though, have been disappointing. As the pie-chart below shows, the vast majority (88%) of attempts by New Zealand citizens to initiate referenda have ended in failure, with petitions failing to be presented in Parliament within a year with the required number of voters’ signatures. Of the remaining 13%, more than two thirds (9%) had their result rejected by the government of the day (National, in three out of the five cases, and Labour in the other two). The total number of citizens-initiated referenda which have succeeded in changing anything since this route to popular participation was introduced is zero.

Click to view

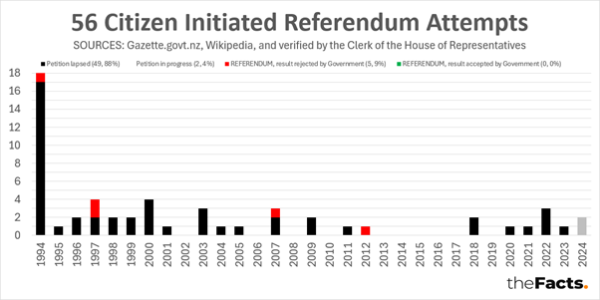

Unsurprisingly in view of this, enthusiasm for citizens-initiated referenda seems to have waned since their introduction. After an initial flurry of nearly twenty attempts in the year after they were brought in, attempts at citizens-initiated referenda slowed to a trickle. There have been no successful attempts by citizens to trigger a referendum since 2013’s plebiscite on the sale of state assets, when the National government proceeded with its privatisation plans despite more than two thirds of votes cast being against them.

Click to view

The second main way that national referenda can be held is if the government arranges one. New Zealand governments have so far done this 44 times in total. But these have been on a narrow range of questions. No fewer than 30 of these referenda focused on the prohibition of alcohol, three concerned the electoral system, and two referenda each asked voters about when pubs should close, how long a parliamentary term should be, and what the national flag should look like.

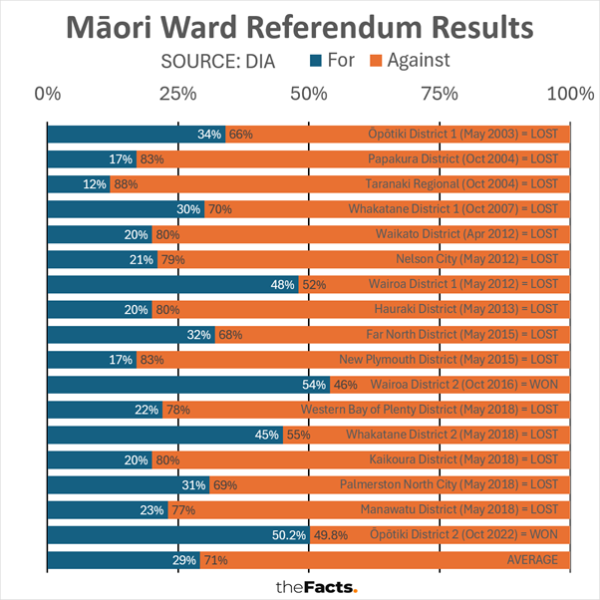

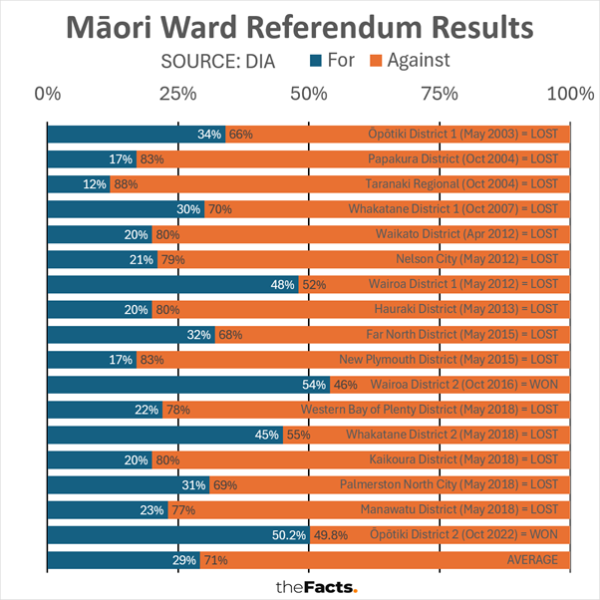

The most common type of referendum in New Zealand in recent years has been the local plebiscite on Māori wards. 17 Māori ward referenda have been held between 2003 and 2022, with a further 42 (only two fewer than the total number of national referenda in our history) slated for this year. As the chart below shows, the public has made its view of Māori wards very clear, with voters rejecting them in 15 of the 17 referenda (and in 15 of the 15 first-time referenda), at nine of them (just more than half) by a margin of more than three votes to one.

Click to view

In spite of this, in 2021 the Labour government removed the requirement for local referenda to be held before Māori wards can be established. By the 2022 local elections, six regional councils and 29 territorial authorities had Māori constituencies or wards. In five districts, councils voted to overturn the clear results of referenda that had taken place only a few years previously.

The first priority for anyone who wants to see more citizen involvement in New Zealand politics should be to revive and renew these already-existing institutions. Parliament could consider introducing a provision for mandatory referenda on changes to the constitution, one of a number of practices which ensure that there is a crop of national referenda every year in Switzerland.

Electronic signatures could be allowed on petitions for citizens-initiated referenda, as they already are on parliamentary petitions. (Section 12 of the Citizens Initiated Referenda Act allows the Parliamentary Clerk to consult on and approve ‘the form to be used for the collection of signatures.’)

Parliament might also consider lowering the 10% threshold to trigger a national referendum to 5%. This is the percentage of registered voters needed to trigger a local referendum on Māori wards, which we have seen has been the most common form of plebiscite in recent years. We could also consider establishing a higher threshold (perhaps 15%) to trigger a binding referendum at the national level.

Besides repairing our existing infrastructure for citizen engagement, though, we should also look to build new channels for public participation.

Fortunately, New Zealand has a number of academics and activists with a practical as well as a theoretical interest in sortition. In the past few years the Centre for Informed Futures at the University of Auckland has facilitated a number of citizens’ assemblies on Auckland water infrastructure (August and September 2022), the future of transport in New Zealand (February and March 2023) and in Auckland (September 2023), and land use in Tairāwhiti (November 2023). In September 2023 Wellington City Council also held a citizens’ assembly on the city’s long-term plan.

Most of these experiments have suffered from similar limitations to previous citizens’ assemblies in other countries. The results of citizens’ deliberations have not always been followed up with detailed reports or concrete recommendations, and even when these have been forthcoming they have largely been ignored by politicians. As with jury duty, citizens’ assemblies in this country have also struggled with a turnout problem – one that has long struck at the heart of their democratic appeal. The Wellington citizens’ assembly involved only 42 people, despite 10,000 initial invitations being sent out.

New Zealand’s sortitionists might benefit from integrating more with the broader direct democracy movement (and its offshoots in this country), which tends to put more stress on referenda (especially citizens-initiated referenda). Referenda have the advantage of including much larger proportions of the total population, even if they do so in a much more cursory way than deliberative assemblies. Ultimately, deepening democracy in New Zealand will probably need both more and better-designed citizens’ assemblies and more and easier-to-trigger national plebiscites.

It will also need to deepen democracy at the local as well as the national level. In a recent New Zealand Initiative report on improving democratic oversight in local councils, Nick Clark has suggested that local referenda could be held on ‘major capital projects above a certain value, new areas of council activity beyond core services, and special levies for specific infrastructure projects.’ Clark also suggests combining the roles of Mayor and Council CEO to help ensure that what voters voted for can be enacted.

Pursuing these avenues will not turn New Zealand into a democratic utopia overnight. Nor does giving the people more power guarantee that all their decisions will be wise ones (even if the example of Switzerland, long one of the richest countries in the world, does suggest that more radical forms of democracy are at least compatible with extremely high levels of development).

What revitalising our democracy might do, though, is go some way towards lessening the gap between the elites that currently dominate the state apparatus and the ordinary people of this country. Giving people more of a say in how the country is run might also help address some of the increasing resentment felt by the marginalised. It would also, at long last, help put the dēmos back in democracy – something New Zealand, which has long been at the forefront of democratic innovation, might take pride in once again leading the world in.

Dr James Kierstead is Senior Lecturer in Classics at Victoria University of Wellington.

Geoff Neal, based in Auckland, is currently a Co-Founder at Kiwi Performance Indicators and a co-founder of theFacts.

Here in New Zealand, too, there is a disconnect between politicians and the people they represent.

In recent years, governments have enacted a number of policies that were clearly opposed by most Kiwis. ‘Three waters’ legislation was forced through despite multiple polls consistently showing that a majority of New Zealanders opposed it. Only a year after Three Strikes legislation was repealed, a poll suggested that nearly two thirds of New Zealanders wanted it to stay on the books (and only 16% wanted it repealed). And despite polls suggesting that clear majorities of Kiwis support the actual wording of the Treaty Principles Bill, it failed to progress beyond its second reading.

What’s the solution? More direct input from citizens. This, after all, is what democracy is supposed to be about. The ancient Greek word dēmokratia meant ‘rule by the people’ (the dēmos) and the first democratic states in the Greek world involved much more direct participation by citizens than our modern, representative systems.

In Athens, the largest and best-documented democracy, citizens voted directly on decisions facing the city in assemblies that met thirty or forty times a year. They could volunteer to be randomly allotted into service on the state council, as a city official, or as a juror in the city’s popular courts. They could even vote to hold an ‘ostracism,’ a kind of unpopularity contest in which the ‘winning’ politician would be exiled from Athens for ten years.

Nowadays, that last procedure might raise worries about human rights. And ostracism is just one feature of ancient Athenian democracy that we would probably not want to revive in the modern day. (Two others are slavery and the exclusion of women and virtually all immigrants from political participation.) But we are not alone in believing that the more direct democratic institutions of ancient Greece can help inspire and inform democratic innovation today.

In fact, academics and activists have been experimenting with direct democratic ideas for decades now. Participatory budgeting, in which local citizens take part in balancing the books in their municipality, has been tried out in over a hundred cities, mainly in Brazil. Direct votes on public issues through referenda have become increasingly common, not only in Switzerland (which has held nine or ten a year in recent decades), but also in California, where citizens can initiate referenda themselves, and in the United Kingdom, where three referenda (one of them legally binding) on major public issues have taken place in the last fifteen years.

The ancient democratic instrument which has been most enthusiastically explored in recent years, though, has been sortition (random allotment). James Fishkin started holding his ‘deliberative polls,’ which bring randomly-selected citizens together to discuss public issues, in the 1990s. Since then, randomly-selected ‘citizens’ assemblies’ have multiplied, with dozens taking place around the world just in the past few years. Organisations dedicated to the ideal of ‘deliberative democracy,’ like the UK-based Sortition Foundation, continue to disseminate citizens’ assemblies worldwide.

New Zealand currently has two main routes to plebiscites at the national level. The first route was opened up by the 1993 Citizens Initiated Referenda Act. This allowed citizens to trigger a non-binding referendum by presenting a petition signed by more than 10% of registered voters to Parliament within a year. This is the most democratic mechanism for triggering a referendum, as citizens get to choose the topic of the plebiscite themselves.

The results, though, have been disappointing. As the pie-chart below shows, the vast majority (88%) of attempts by New Zealand citizens to initiate referenda have ended in failure, with petitions failing to be presented in Parliament within a year with the required number of voters’ signatures. Of the remaining 13%, more than two thirds (9%) had their result rejected by the government of the day (National, in three out of the five cases, and Labour in the other two). The total number of citizens-initiated referenda which have succeeded in changing anything since this route to popular participation was introduced is zero.

Click to view

Unsurprisingly in view of this, enthusiasm for citizens-initiated referenda seems to have waned since their introduction. After an initial flurry of nearly twenty attempts in the year after they were brought in, attempts at citizens-initiated referenda slowed to a trickle. There have been no successful attempts by citizens to trigger a referendum since 2013’s plebiscite on the sale of state assets, when the National government proceeded with its privatisation plans despite more than two thirds of votes cast being against them.

Click to view

The second main way that national referenda can be held is if the government arranges one. New Zealand governments have so far done this 44 times in total. But these have been on a narrow range of questions. No fewer than 30 of these referenda focused on the prohibition of alcohol, three concerned the electoral system, and two referenda each asked voters about when pubs should close, how long a parliamentary term should be, and what the national flag should look like.

The most common type of referendum in New Zealand in recent years has been the local plebiscite on Māori wards. 17 Māori ward referenda have been held between 2003 and 2022, with a further 42 (only two fewer than the total number of national referenda in our history) slated for this year. As the chart below shows, the public has made its view of Māori wards very clear, with voters rejecting them in 15 of the 17 referenda (and in 15 of the 15 first-time referenda), at nine of them (just more than half) by a margin of more than three votes to one.

Click to view

In spite of this, in 2021 the Labour government removed the requirement for local referenda to be held before Māori wards can be established. By the 2022 local elections, six regional councils and 29 territorial authorities had Māori constituencies or wards. In five districts, councils voted to overturn the clear results of referenda that had taken place only a few years previously.

The first priority for anyone who wants to see more citizen involvement in New Zealand politics should be to revive and renew these already-existing institutions. Parliament could consider introducing a provision for mandatory referenda on changes to the constitution, one of a number of practices which ensure that there is a crop of national referenda every year in Switzerland.

Electronic signatures could be allowed on petitions for citizens-initiated referenda, as they already are on parliamentary petitions. (Section 12 of the Citizens Initiated Referenda Act allows the Parliamentary Clerk to consult on and approve ‘the form to be used for the collection of signatures.’)

Parliament might also consider lowering the 10% threshold to trigger a national referendum to 5%. This is the percentage of registered voters needed to trigger a local referendum on Māori wards, which we have seen has been the most common form of plebiscite in recent years. We could also consider establishing a higher threshold (perhaps 15%) to trigger a binding referendum at the national level.

Besides repairing our existing infrastructure for citizen engagement, though, we should also look to build new channels for public participation.

Fortunately, New Zealand has a number of academics and activists with a practical as well as a theoretical interest in sortition. In the past few years the Centre for Informed Futures at the University of Auckland has facilitated a number of citizens’ assemblies on Auckland water infrastructure (August and September 2022), the future of transport in New Zealand (February and March 2023) and in Auckland (September 2023), and land use in Tairāwhiti (November 2023). In September 2023 Wellington City Council also held a citizens’ assembly on the city’s long-term plan.

Most of these experiments have suffered from similar limitations to previous citizens’ assemblies in other countries. The results of citizens’ deliberations have not always been followed up with detailed reports or concrete recommendations, and even when these have been forthcoming they have largely been ignored by politicians. As with jury duty, citizens’ assemblies in this country have also struggled with a turnout problem – one that has long struck at the heart of their democratic appeal. The Wellington citizens’ assembly involved only 42 people, despite 10,000 initial invitations being sent out.

New Zealand’s sortitionists might benefit from integrating more with the broader direct democracy movement (and its offshoots in this country), which tends to put more stress on referenda (especially citizens-initiated referenda). Referenda have the advantage of including much larger proportions of the total population, even if they do so in a much more cursory way than deliberative assemblies. Ultimately, deepening democracy in New Zealand will probably need both more and better-designed citizens’ assemblies and more and easier-to-trigger national plebiscites.

It will also need to deepen democracy at the local as well as the national level. In a recent New Zealand Initiative report on improving democratic oversight in local councils, Nick Clark has suggested that local referenda could be held on ‘major capital projects above a certain value, new areas of council activity beyond core services, and special levies for specific infrastructure projects.’ Clark also suggests combining the roles of Mayor and Council CEO to help ensure that what voters voted for can be enacted.

Pursuing these avenues will not turn New Zealand into a democratic utopia overnight. Nor does giving the people more power guarantee that all their decisions will be wise ones (even if the example of Switzerland, long one of the richest countries in the world, does suggest that more radical forms of democracy are at least compatible with extremely high levels of development).

What revitalising our democracy might do, though, is go some way towards lessening the gap between the elites that currently dominate the state apparatus and the ordinary people of this country. Giving people more of a say in how the country is run might also help address some of the increasing resentment felt by the marginalised. It would also, at long last, help put the dēmos back in democracy – something New Zealand, which has long been at the forefront of democratic innovation, might take pride in once again leading the world in.

Dr James Kierstead is Senior Lecturer in Classics at Victoria University of Wellington.

Geoff Neal, based in Auckland, is currently a Co-Founder at Kiwi Performance Indicators and a co-founder of theFacts.

This article was first published HERE

5 comments:

When the marginalised are the majority and things like the establishment of racist maori wards are forced upon them….despite multiple attempts by participating citizens to prevent their establishment - then the plebs start to revolt!

Love the terms from classics…the plebs are revolting!

We the plebs are simply lacking the organisation to revolt right now but the covid protests showed us how to make it happen.

So make it happen plebs - it’s time to revolt!

Citizens initiated referenda requires too high a threshold. I think it is 300,000 signatures. Even when the threshold is met, it is not binding. Therefore this is only an option for the very tenacious citizen to pursue. Most citizens are too apathetic now as they see that no matter how many petitions they sign, emails they write or submissions they put forward it is totally disregarded by those in power. Politicians are not concerned about those that vote for them, rather, they pursue their own agendas. He Puapua, Three Waters, Maori Wards, Maori Seats, and The Waitangi Tribunal would all be rejected by those who consider we are one country, all New Zealanders, and not tribal entities. As I said about the US recently, there are many, many intelligent people outside government who vote and the same applies here. The politicians definitely don't have a monopoly on high IQ.

Well done Geoff and James, for this thoughtful and well researched article. But… if you want real change, and an end to rule by the entitled elite, you must put an end to party politics. This could be done by using an old example from before your time… CMT and NSTU selection programmes. Young men were selected by ballot, then assessed for suitability for military service. The same system could be adapted to select for our reps in Parliament. A strict filter would be needed to ensure competency, capability and maturity, amongst other characteristics. A limited term, say 6 years, would be an absolute. A much easier means of initiating referenda should be introduced. An upper house, with identical provisions of entry would be required. Absolute control of appointment to heads of depts would be essential. I’m sure you guys could think of other attributes needed, but the real essential remains - abandon political parties.

Clearly MPs are past their "UseBy date". Lazy self satisfied leeches with inflated egos on inflated salaries. Citizens referenda need better implementations, and refined by better use. Interesting that one of the writers of this article is a "Classics" lecturer. I thought such were outmoded and any thought of "democracy" as in the Greek forum quite quaint. Comeback Aristotle and Plato... the WORLD needs you !!

This latest racist education budget appropriation by Hon Erica Stanford and National is disgraceful and frankly the absolute pits . PM Luxon and his National caucus are actually traitors to the voting public when announcing this maori education behemoth carefully hidden in the budget . Yes probably malpractice in office and political misfeasance will be their legacy. Luxon has to go away, as far from NZ as possible .

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.