I would not usually devote a column for The Australian to problems with a New Zealand local council.

Nevertheless, the city in question is the capital, so I will make an exception. Also, Wellington’s problems are indicative of the state of New Zealand’s local government more generally.

A decade ago, in 2013, then-Prime Minister John Key declared Wellington a “dying city.” It was controversial enough that Key had to retract his statement shortly afterwards. Today, however, many New Zealanders might agree with Key.

Wellington has recently made headlines, including in Australia, for all the wrong reasons. Most shockingly because there is a real chance that New Zealand’s capital may run out of water.

If you have ever been to Wellington, you may find this surprising. The city receives around 1250 millimetres of rain per year. Rainfall is spread relatively evenly throughout the year with no distinct wet or dry season. On average, it rains on one day of every three. It is not particularly warm, either.

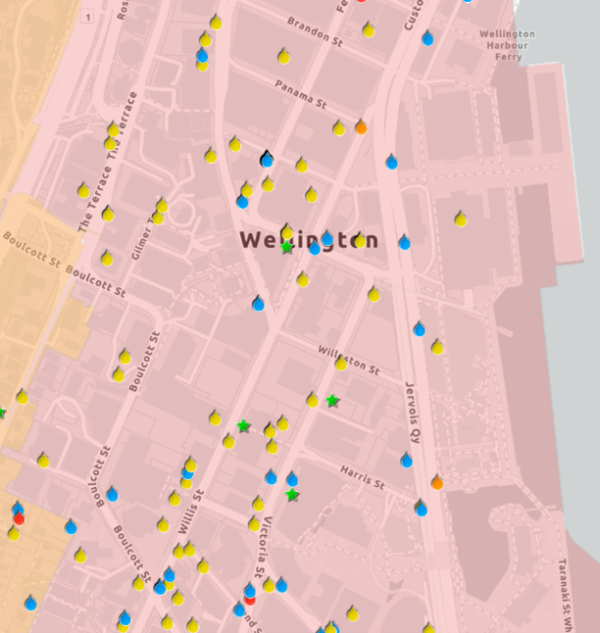

Current reported water leaks in central Wellington,

source: https://www.wellingtonwater.co.nz/resources/maps/job-status-map/

Click image to view

All that rain falls on not too many people, which makes Wellington’s water shortage even more astonishing. Wellington City has a population of around 220,000, while the Greater Wellington population is just over half a million. There are 746 people per square kilometre in the city and 68 people per square kilometre in the region.

The fact that Wellington is not doing well reminds me of a quip by Milton Friedman: “If the federal government ran the Sahara Desert, there would be a shortage of sand within five years.”

The woes of Wellington are man-made. Or, more precisely, they are a product of local government.

To understand this, you only need to stroll around the capital. You will struggle to walk for more than five minutes without running into a puddle, even on dry and sunny days.

That is because leaks are everywhere in the city. Some are small, others create impromptu fountains, and most take weeks, if not months, to repair. While one is being fixed, another two or three typically crop up elsewhere.

On Wellington Water’s online map, you can check every reported leak and its effect on the local water supply. At the moment, most of the city is coloured in pink, meaning high water losses.

In Wellington, not only are freshwater pipes breaking, but raw sewage has occasionally run through the streets. In some cases, Wellington’s water situation stinks – quite literally.

For the capital of an OECD economy, a member of the Five Eyes, and a country that likes to think of itself as Godzone, this is not good enough.

Most people do not think much about getting clean water from taps or flushing their toilets. In any developed country, a reliable water supply is taken for granted. And, probably for that reason, running the waterworks or installing pipes is not seen as glamorous, visionary or exciting.

Over many years, Wellington’s mayors and councillors have presided over an ageing network of pipes that cried out for repair and renewal, but local officials found other projects more enticing.

There are, of course, different projects that appeal to politicians of different hues. The same holds for different electorates.

The electorate in Wellington is primarily made up of civil servants. It is the national capital, after all. Wellington also has a vibrant arts and film scene. There are university students and academics, too.

The private sector, however, has largely withdrawn from Wellington over the years. Wellington’s ‘business differential,’ the extra rates charged to businesses compared to residences, is the highest in the country. There are few corporate headquarters left.

It is no secret that Wellington’s electorate has a left-of-centre tilt. It was in the capital where the Greens won two of their three electorate seats in last year’s general election. In Wellington’s local elections, left-of-centre candidates have usually won most wards and the mayoralty.

Without wishing to stereotype, Wellington City Council’s projects reflect these political leanings. Cycleways have been built in places where few people ride bikes. The rainbow-coloured crossing in the entertainment district is, well, striking. Recently, the city installed solar-powered parking ticket machines capable of communicating with in both English and Māori – when they work.

However, all the council’s investments in traffic slowing, traffic reduction and climate change outreach pale into insignificance compared to a few big-ticket items.

Right opposite the national museum, Wellington now boasts a swish new convention centre. It is called Tākina. At NZ$184 million, it was only a bit more than NZ$5 million over budget. What a pity though that Wellington’s ratepayers will be left funding 40 percent of its ongoing costs in perpetuity because there is no need for a convention centre of that size.

Additionally, Wellington’s ratepayers will be responsible for the reconstruction of the city library and town hall complex due to the earthquake-prone nature of the buildings. Bulldozing the plot and starting again would have been cheaper, but heritage rules obviously must be followed.

Running through the city council’s expenditure of questionable value, it becomes clear that any possibility of funding water pipes has dried up. Never mind that Wellington’s local rates on businesses are the highest in New Zealand, and that residential rates are higher than Auckland’s.

Perhaps deep down, councillors hoped the national government would eventually come to their rescue. After all, former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern signalled a wish to nationalise all water infrastructure. And wouldn’t it have been nice to offload all of Wellington city’s problems to Wellington, the capital?

Alas, these plans would have been disastrous in their own ways – not least because they would have been horrendously expensive. And so, Wellington is now left to its own devices to figure out how to deal with bursting pipes and drained taps.

Right now, no one has a clue, least of all the council. Meanwhile, all that new local government minister Simeon Brown can do for now is send ‘Please explain!’ letters to everyone involved in the fiasco.

Wellington’s water woes are a tragicomedy, but they are New Zealand’s local government problem in a nutshell. We should not expect good policy outcomes when cities are run by ideologues, when voters do not care for costs and benefits, and when councils speculate on being bailed out by the national government.

Wellington, of course, remains a wonderful place. With its temperate climate, scenic harbour and thriving population of friendly bureaucrats, it is always worth a visit. Just stay away from puddles in the street, and do not take long showers.

As they say, you cannot beat Wellington on a good day. And at least it isn’t Canberra.

Dr Oliver Hartwich is the Executive Director of The New Zealand Initiative think tank. This article was first published HERE.

If you have ever been to Wellington, you may find this surprising. The city receives around 1250 millimetres of rain per year. Rainfall is spread relatively evenly throughout the year with no distinct wet or dry season. On average, it rains on one day of every three. It is not particularly warm, either.

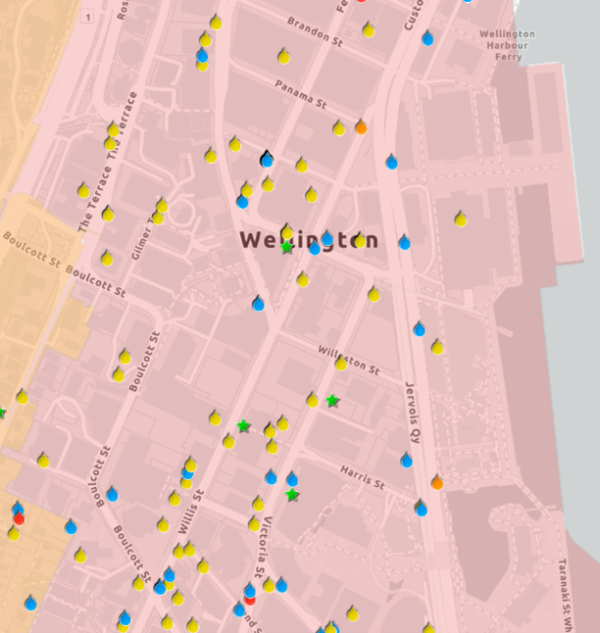

Current reported water leaks in central Wellington,

source: https://www.wellingtonwater.co.nz/resources/maps/job-status-map/

Click image to view

All that rain falls on not too many people, which makes Wellington’s water shortage even more astonishing. Wellington City has a population of around 220,000, while the Greater Wellington population is just over half a million. There are 746 people per square kilometre in the city and 68 people per square kilometre in the region.

The fact that Wellington is not doing well reminds me of a quip by Milton Friedman: “If the federal government ran the Sahara Desert, there would be a shortage of sand within five years.”

The woes of Wellington are man-made. Or, more precisely, they are a product of local government.

To understand this, you only need to stroll around the capital. You will struggle to walk for more than five minutes without running into a puddle, even on dry and sunny days.

That is because leaks are everywhere in the city. Some are small, others create impromptu fountains, and most take weeks, if not months, to repair. While one is being fixed, another two or three typically crop up elsewhere.

On Wellington Water’s online map, you can check every reported leak and its effect on the local water supply. At the moment, most of the city is coloured in pink, meaning high water losses.

In Wellington, not only are freshwater pipes breaking, but raw sewage has occasionally run through the streets. In some cases, Wellington’s water situation stinks – quite literally.

For the capital of an OECD economy, a member of the Five Eyes, and a country that likes to think of itself as Godzone, this is not good enough.

Most people do not think much about getting clean water from taps or flushing their toilets. In any developed country, a reliable water supply is taken for granted. And, probably for that reason, running the waterworks or installing pipes is not seen as glamorous, visionary or exciting.

Over many years, Wellington’s mayors and councillors have presided over an ageing network of pipes that cried out for repair and renewal, but local officials found other projects more enticing.

There are, of course, different projects that appeal to politicians of different hues. The same holds for different electorates.

The electorate in Wellington is primarily made up of civil servants. It is the national capital, after all. Wellington also has a vibrant arts and film scene. There are university students and academics, too.

The private sector, however, has largely withdrawn from Wellington over the years. Wellington’s ‘business differential,’ the extra rates charged to businesses compared to residences, is the highest in the country. There are few corporate headquarters left.

It is no secret that Wellington’s electorate has a left-of-centre tilt. It was in the capital where the Greens won two of their three electorate seats in last year’s general election. In Wellington’s local elections, left-of-centre candidates have usually won most wards and the mayoralty.

Without wishing to stereotype, Wellington City Council’s projects reflect these political leanings. Cycleways have been built in places where few people ride bikes. The rainbow-coloured crossing in the entertainment district is, well, striking. Recently, the city installed solar-powered parking ticket machines capable of communicating with in both English and Māori – when they work.

However, all the council’s investments in traffic slowing, traffic reduction and climate change outreach pale into insignificance compared to a few big-ticket items.

Right opposite the national museum, Wellington now boasts a swish new convention centre. It is called Tākina. At NZ$184 million, it was only a bit more than NZ$5 million over budget. What a pity though that Wellington’s ratepayers will be left funding 40 percent of its ongoing costs in perpetuity because there is no need for a convention centre of that size.

Additionally, Wellington’s ratepayers will be responsible for the reconstruction of the city library and town hall complex due to the earthquake-prone nature of the buildings. Bulldozing the plot and starting again would have been cheaper, but heritage rules obviously must be followed.

Running through the city council’s expenditure of questionable value, it becomes clear that any possibility of funding water pipes has dried up. Never mind that Wellington’s local rates on businesses are the highest in New Zealand, and that residential rates are higher than Auckland’s.

Perhaps deep down, councillors hoped the national government would eventually come to their rescue. After all, former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern signalled a wish to nationalise all water infrastructure. And wouldn’t it have been nice to offload all of Wellington city’s problems to Wellington, the capital?

Alas, these plans would have been disastrous in their own ways – not least because they would have been horrendously expensive. And so, Wellington is now left to its own devices to figure out how to deal with bursting pipes and drained taps.

Right now, no one has a clue, least of all the council. Meanwhile, all that new local government minister Simeon Brown can do for now is send ‘Please explain!’ letters to everyone involved in the fiasco.

Wellington’s water woes are a tragicomedy, but they are New Zealand’s local government problem in a nutshell. We should not expect good policy outcomes when cities are run by ideologues, when voters do not care for costs and benefits, and when councils speculate on being bailed out by the national government.

Wellington, of course, remains a wonderful place. With its temperate climate, scenic harbour and thriving population of friendly bureaucrats, it is always worth a visit. Just stay away from puddles in the street, and do not take long showers.

As they say, you cannot beat Wellington on a good day. And at least it isn’t Canberra.

Dr Oliver Hartwich is the Executive Director of The New Zealand Initiative think tank. This article was first published HERE.

1 comment:

Rolling on floor laughing. No one has ever liked Wellington ( except me, a wonderful place to live).

Auckland is a mess too and just as windy - what do you need to be a city of sails?

Yet for some reason living in a humid overpopulated disorganised dysfunctional dump on top of a live volcanic system is deemed infinitely superior to any where else in NZ.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.