A guide to help concerned citizens organise for the next election. The system is broken.

Hamilton City Councillor Andrew Bydder has written a lengthy and detailed article for the Good Oil to help readers concerned about our local councils to get prepared for the next LGNZ elections. This is part three. [Ed.]

PART C - WHAT ARE THE PROBLEMS?

It is so easy to be wrong – and to persist in being wrong – when the costs of being wrong are paid by others. - Thomas Sowell

There are three key root causes of problems that I address in this document:

1. STRUCTURE – the way councils are organised controls how they function.

2. FINANCES – councils don’t have a rates problem, they have a spending problem.

3. PEOPLE – the inmates are running the asylum.

There are several specific problems that I will address in future documents. These include:

· THREE WATERS – the same staff who oversaw the current failures will run the new organisations.

· LOCAL GOVERNMENT NEW ZEALAND – an association originally for elected representatives that has been taken over by woke council staff.

· RESOURCE CONSENTS AND BUILDING CONSENTS – a major factor in the housing affordability crisis.

1 STRUCTURE

(a) Elected representatives (mayor and councillors)

Understanding councils begins with knowing that each council is two, almost entirely separate, organisations. This was set up by the Local Government Act 2002.

Your elected representatives (mayor and councillors) have very limited powers. They set policies, approve budgets and pass bylaws. The scope for bylaws is restricted to specific government acts such as the Sale of Liquor Act, allowing councils to implement alcohol bans in some areas. Decisions are made by majority vote, with each councillor and the mayor having one vote. The mayor gets a casting vote in the event of a tie, which, being rare event, means the mayor essentially has no more power than any other councillor. While the mayor has an important community role as a figurehead for ribbon cutting, handshaking and speech giving, most people are genuinely surprised at how restricted the mayor is as a leader. If a majority voting block opposes the mayor, then the mayor is effectively powerless.

The service provision, council operations and infrastructure projects are all run by council management independently of elected representation. Council staff provide reports to elected representatives and lead briefing sessions, giving councillors all the information staff WANT them to know. This is very different from information the councillors NEED to know. Staff get delegated authority to spend budgets as they see fit, manage their departments, apply policies as they interpret them and employ more staff.

(b) Chief executive

The only crossover is that the elected representatives employ the chief executive. The chief executive employs everyone else, so councillors actually have no direct line of control to any other council staff. This means, at least in theory, the chief executive has the real power, and is typically paid two to three times as much as the mayor.

In practice, the chief executive has limited knowledge of what is going on in most of their organisation. Hamilton City Council, as a typical example, has 28 different business units, plus several council-controlled organisations (CCOs). These range from the core services of roads and waters to community services (such as libraries and theatres), legal functions (such as dog control and building inspections), business functions (such as computer services and human resources) and social assets (such as an airport and a zoo). It is not possible to have expertise in, or even time to consider, so many diverse specialist functions. The chief executive is reduced to an administrative role liaising between staff and the elected representatives.

(c) Managers

The chief executive is reliant on a second tier of general managers, each with half a dozen functions in their portfolio. The general managers suffer the same fate. They may have a greater level of expertise across their portfolio, but are stuck in an administrative role of delegating authority – signing off reports and approving expenditure from the department managers.

It is the third tier, the department managers, that run the council operations. They are removed from accountability to the elected representatives, and, as experts in their field, are often unquestioned by the general managers. Their performance is measured in non-financial criteria. This has a surprising effect: instead of freeing them to make decisions, this lack of being able to justify their choices by hard facts measured in dollar values means they are reluctant to make decisions. Likewise, it incentivises covering up measurable mistakes.

This leads to the dreaded committees. In the private sector, a committee is selected to cover a range of relevant skills in order to get the best decision. In the public sector, a committee is selected so no one person can be blamed for a bad decision. The great socioeconomist, Stanford Professor Thomas Sowell, summed up government by saying, “It is so easy to be wrong – and to persist in being wrong – when the costs of being wrong are paid by others.”

2 FINANCES

Councils don’t have a revenue problem, they have a spending problem.

A recent press release from Local Government New Zealand announced that councils were exploring 20 new ways of raising revenue other than rates. This supposedly positive move ignores the fact that the same public will be paying these new fees and charges from their same limited income. There is no free money. More revenue is not a solution.

Council spending is best understood by splitting it between Operational expenditure (Opex) and Capital expenditure (Capex).

(a) Opex

Operational expenditure is the day-to-day running of the council and providing services. This is fundamentally what rates are supposed to cover. In fact, the Local Government Act section 100 (1) requires councils to balance their operational budget, i.e., ensure that each year’s rates income covers that year’s expenses.

The truth is that most councils are breaking the law by kicking the can down the road every year. Hamilton has failed to balance its budget in 19 of the last 20 years, and is not projected to do so in the next two years either. This is financial mismanagement. The shortfall is covered by borrowing, which means the burden is placed on our children to repay councils living beyond their means now.

The addiction to spending is driven by the easy credit of borrowing. Councils obtain loans from the Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA). If you or I go to the bank for a mortgage, the bank will look at both our income and our expenses to know whether we can afford to pay back the loan. The LGFA only looks at council’s income. This is financial mismanagement.

The only way the LGFA gets away with this is that its loans are secured against future rates income, which councils secure against your house. In the event of a default, the Local Government (Ratings) Act section 69 allows councils to sell your house to recover the money that the council owes on a debt that you were not even told about, let alone agreed to.

(b) Capex

Capital expenditure is the money council spends on community infrastructure. Assets like sewage treatment plants are expensive but last a long time. There is a high up-front cost which is covered by borrowing. This is what debt should be used for, because the cost is repaid over the lifetime of the asset when future ratepayers use it.

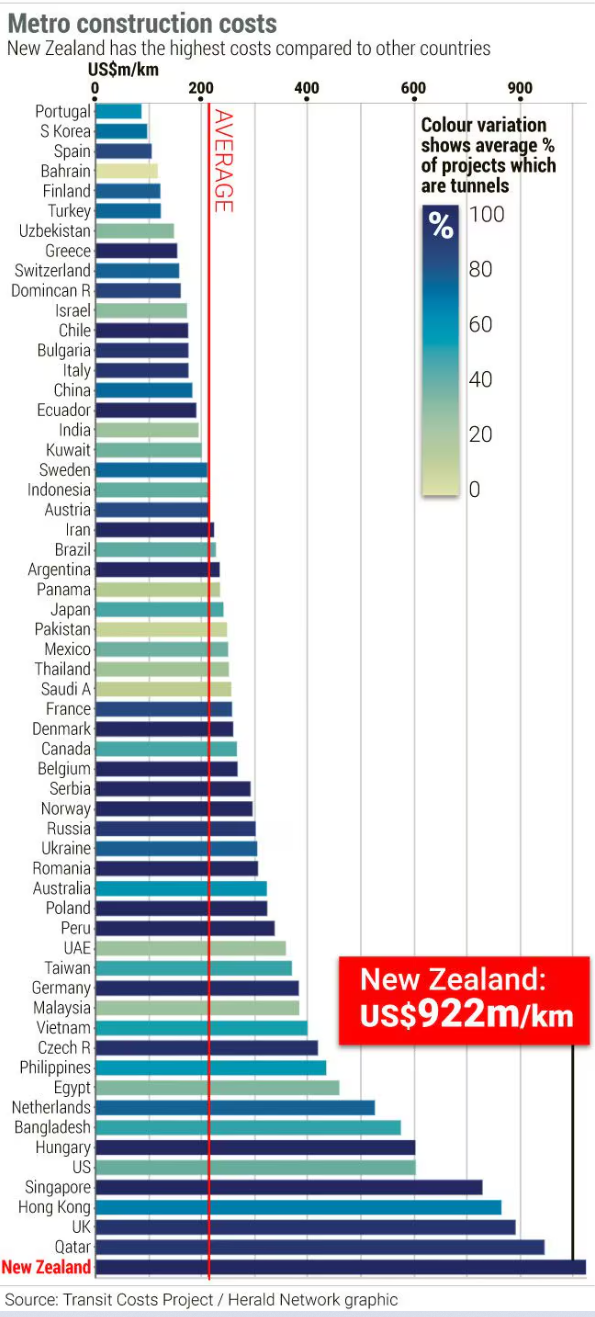

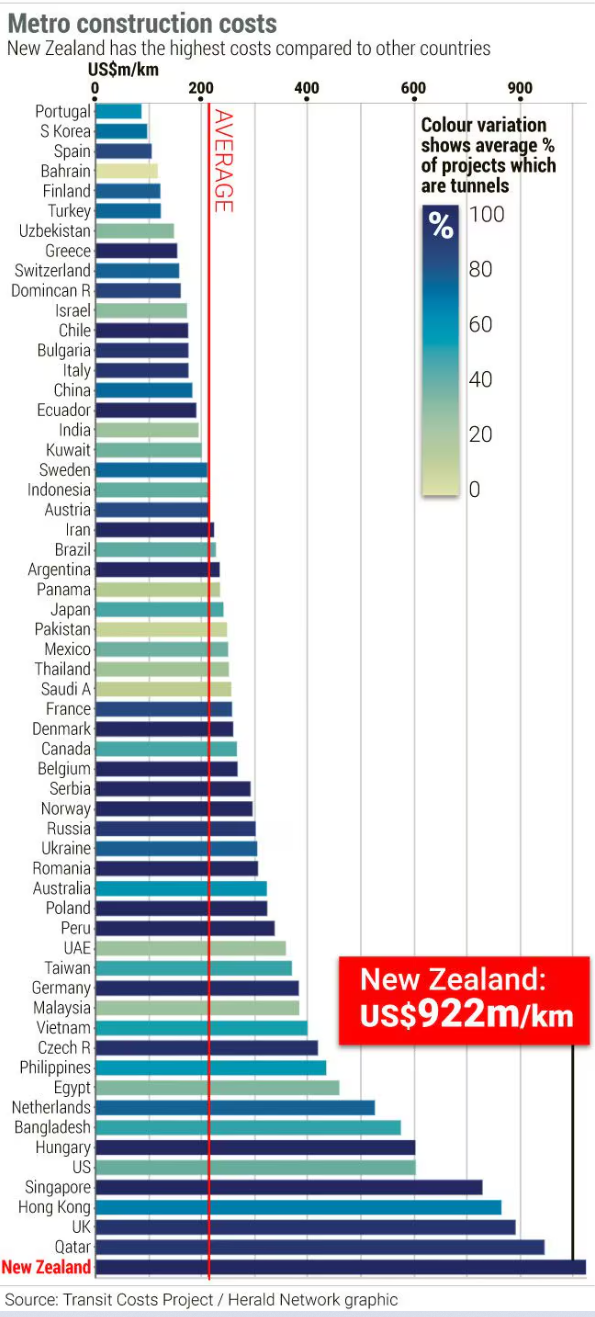

The problem is illustrated in this graph from the New Zealand Herald about city rail infrastructure. New Zealand is the most expensive country in the world: four times the OECD average.

Click to view

The way councils specify and manage infrastructure projects is grossly overpriced. The debt is crippling the country. Hamilton’s 10-year plan projects a debt of $10,000 per person, or $50,000 for an average family.

Historically cheap interest rates since the GFC have encouraged a spending culture on projects with low or no return on investment, such as speed bumps. Prior to the GFC, as far back as 1960, New Zealand averaged 10 per cent mortgage rates. A return to that level would see $5,000 added to the average household per year just to cover debt servicing.

As with Operational expenditure, the LGFA lends money for Capital expenditure based solely on council’s income. There is no consideration for the return on investment. There is no registered valuation of the asset to compare to the inflated construction prices. The easy credit has let financially illiterate councillors buy glamour projects – ‘nice to haves’ – and pursue social engineering agendas that will burden ratepayers for a century.

3 PEOPLE

Council managers, at both the general manager and department manager level, are insulated from voters (governance) and ratepayers (customers), with no clear publicly reported measures of performance. As a result, they appear focused on the process rather than the outcome. So long as the process is followed, they can defend bad outcomes, such as mistakes and failures. This means the process doesn’t get fixed.

Processes are administrative tasks. While they may be based on a series of checks and balances along the way to prevent mistakes, the practical reality is that each approval step is carried out by someone looking at an isolated issue, not the end-to-end delivery, voiding them of responsibility.

Success is achieved by ‘yes’ votes from councillors to accept reports and proposals, because that removes responsibility from the manager. To do that, managers tailor reports to obtain the desired decision, leaving councillors misinformed or uninformed. The result of this blinkered process is poor outcomes – which clearly points to a failed process, yet the process is never questioned.

(d) Staff

There are certainly many good people working for councils and it is simply unfair to tar them all with the same brush. It is equally unfair to pretend that all council employees are faultless. When exposed to complaints, a former chief executive of Hamilton repeatedly claimed he had 100 per cent confidence in his staff. This is mathematically and evidentially blatant mismanagement. He had 1,400 staff, so even if just one per cent made one mistake per year, that is 14 mistakes in need of fixing. I regard myself as a highly skilled and experienced professional, and I make far more mistakes than that every year. The chief executive failed his duties by refusing to acknowledge errors and he was active in covering them up.

The fact is mistakes should be expected. It is human. Admitting them is part of the solution. Covering up means mistakes not only don’t get fixed – they get systematised and repeated.

The lack of accountability should eliminate the fear of admitting mistakes because there are no consequences. Perversely, the opposite is true. The lack of accountability also manifests in an absence of measures for good performance. Employees with good track records, who make occasional errors, feel safe knowing their value outweighs the negatives. Without performance measures, having to admit a mistake is the only consequence and there is nothing to offset it, therefore it becomes the problem to be avoided.

This also leads into task isolation, sometimes called a silo mentality. A staff member given a goal of raising parking revenue will install more parking meters in the central business district. Payments and fines may increase but so do collection and maintenance costs. As frustrated customers abandon the city centre for suburban malls, rates income drops by more than the parking revenue increase. The council is worse off but the staff member has done a ‘good’ job. Management will not admit the mistake.

Silo mentality grows into empire building. Council planning departments have expanded regulations, then expanded staff numbers to manage the regulations, then the new staff expand regulations in a cycle that strangles development.

Another common feature of bureaucracies is the Peter Principle derivative known as the Dilbert Principle (named after the cartoon). This states that in large organisations people rise to their level of incompetence. A competent person will get promoted as a reward, rising up through the ranks. However, when the person is evidently no longer competent at the complex tasks of a current role, he or she will not get any further promotions and will be stuck in the incompetent role.

Finally, we must consider what type of person chooses to work for councils. It is a simple truth that people with creativity and initiative will avoid bureaucratic organisations. Others will use council positions as stepping stones to a career outside council – those with ‘get-up-and-go’ will get up and go. Without doubt, some people have seen councils as a position of authority and a resource to use for their social agendas. The lack of accountability protects them and gives freedom to spend other people’s money. Once ensconced, they employ like-minded people. There has been a fundamental and coordinated culture shift in councils over the last decade that is not working for ratepayers.

This is the third part of a series. Part A is here and part B is here.

Andrew Bydder is a is a Hamilton City Councillor, a professional problem solver, a designer, and a small business owner. This article was first published HERE

There are three key root causes of problems that I address in this document:

1. STRUCTURE – the way councils are organised controls how they function.

2. FINANCES – councils don’t have a rates problem, they have a spending problem.

3. PEOPLE – the inmates are running the asylum.

There are several specific problems that I will address in future documents. These include:

· THREE WATERS – the same staff who oversaw the current failures will run the new organisations.

· LOCAL GOVERNMENT NEW ZEALAND – an association originally for elected representatives that has been taken over by woke council staff.

· RESOURCE CONSENTS AND BUILDING CONSENTS – a major factor in the housing affordability crisis.

1 STRUCTURE

(a) Elected representatives (mayor and councillors)

Understanding councils begins with knowing that each council is two, almost entirely separate, organisations. This was set up by the Local Government Act 2002.

Your elected representatives (mayor and councillors) have very limited powers. They set policies, approve budgets and pass bylaws. The scope for bylaws is restricted to specific government acts such as the Sale of Liquor Act, allowing councils to implement alcohol bans in some areas. Decisions are made by majority vote, with each councillor and the mayor having one vote. The mayor gets a casting vote in the event of a tie, which, being rare event, means the mayor essentially has no more power than any other councillor. While the mayor has an important community role as a figurehead for ribbon cutting, handshaking and speech giving, most people are genuinely surprised at how restricted the mayor is as a leader. If a majority voting block opposes the mayor, then the mayor is effectively powerless.

The service provision, council operations and infrastructure projects are all run by council management independently of elected representation. Council staff provide reports to elected representatives and lead briefing sessions, giving councillors all the information staff WANT them to know. This is very different from information the councillors NEED to know. Staff get delegated authority to spend budgets as they see fit, manage their departments, apply policies as they interpret them and employ more staff.

(b) Chief executive

The only crossover is that the elected representatives employ the chief executive. The chief executive employs everyone else, so councillors actually have no direct line of control to any other council staff. This means, at least in theory, the chief executive has the real power, and is typically paid two to three times as much as the mayor.

In practice, the chief executive has limited knowledge of what is going on in most of their organisation. Hamilton City Council, as a typical example, has 28 different business units, plus several council-controlled organisations (CCOs). These range from the core services of roads and waters to community services (such as libraries and theatres), legal functions (such as dog control and building inspections), business functions (such as computer services and human resources) and social assets (such as an airport and a zoo). It is not possible to have expertise in, or even time to consider, so many diverse specialist functions. The chief executive is reduced to an administrative role liaising between staff and the elected representatives.

(c) Managers

The chief executive is reliant on a second tier of general managers, each with half a dozen functions in their portfolio. The general managers suffer the same fate. They may have a greater level of expertise across their portfolio, but are stuck in an administrative role of delegating authority – signing off reports and approving expenditure from the department managers.

It is the third tier, the department managers, that run the council operations. They are removed from accountability to the elected representatives, and, as experts in their field, are often unquestioned by the general managers. Their performance is measured in non-financial criteria. This has a surprising effect: instead of freeing them to make decisions, this lack of being able to justify their choices by hard facts measured in dollar values means they are reluctant to make decisions. Likewise, it incentivises covering up measurable mistakes.

This leads to the dreaded committees. In the private sector, a committee is selected to cover a range of relevant skills in order to get the best decision. In the public sector, a committee is selected so no one person can be blamed for a bad decision. The great socioeconomist, Stanford Professor Thomas Sowell, summed up government by saying, “It is so easy to be wrong – and to persist in being wrong – when the costs of being wrong are paid by others.”

2 FINANCES

Councils don’t have a revenue problem, they have a spending problem.

A recent press release from Local Government New Zealand announced that councils were exploring 20 new ways of raising revenue other than rates. This supposedly positive move ignores the fact that the same public will be paying these new fees and charges from their same limited income. There is no free money. More revenue is not a solution.

Council spending is best understood by splitting it between Operational expenditure (Opex) and Capital expenditure (Capex).

(a) Opex

Operational expenditure is the day-to-day running of the council and providing services. This is fundamentally what rates are supposed to cover. In fact, the Local Government Act section 100 (1) requires councils to balance their operational budget, i.e., ensure that each year’s rates income covers that year’s expenses.

The truth is that most councils are breaking the law by kicking the can down the road every year. Hamilton has failed to balance its budget in 19 of the last 20 years, and is not projected to do so in the next two years either. This is financial mismanagement. The shortfall is covered by borrowing, which means the burden is placed on our children to repay councils living beyond their means now.

The addiction to spending is driven by the easy credit of borrowing. Councils obtain loans from the Local Government Funding Agency (LGFA). If you or I go to the bank for a mortgage, the bank will look at both our income and our expenses to know whether we can afford to pay back the loan. The LGFA only looks at council’s income. This is financial mismanagement.

The only way the LGFA gets away with this is that its loans are secured against future rates income, which councils secure against your house. In the event of a default, the Local Government (Ratings) Act section 69 allows councils to sell your house to recover the money that the council owes on a debt that you were not even told about, let alone agreed to.

(b) Capex

Capital expenditure is the money council spends on community infrastructure. Assets like sewage treatment plants are expensive but last a long time. There is a high up-front cost which is covered by borrowing. This is what debt should be used for, because the cost is repaid over the lifetime of the asset when future ratepayers use it.

The problem is illustrated in this graph from the New Zealand Herald about city rail infrastructure. New Zealand is the most expensive country in the world: four times the OECD average.

Click to view

The way councils specify and manage infrastructure projects is grossly overpriced. The debt is crippling the country. Hamilton’s 10-year plan projects a debt of $10,000 per person, or $50,000 for an average family.

Historically cheap interest rates since the GFC have encouraged a spending culture on projects with low or no return on investment, such as speed bumps. Prior to the GFC, as far back as 1960, New Zealand averaged 10 per cent mortgage rates. A return to that level would see $5,000 added to the average household per year just to cover debt servicing.

As with Operational expenditure, the LGFA lends money for Capital expenditure based solely on council’s income. There is no consideration for the return on investment. There is no registered valuation of the asset to compare to the inflated construction prices. The easy credit has let financially illiterate councillors buy glamour projects – ‘nice to haves’ – and pursue social engineering agendas that will burden ratepayers for a century.

3 PEOPLE

(a) Elected representatives

As noted in the BACKGROUND chapter, councils are fundamentally engineering and property management companies. A brief glance at elected representatives across councils reveals kindergarten teachers, a bar maid, student activists who have never held real jobs, a preponderance of Māori-first separatists, union agitators and cycle advocates. It should not come as any surprise that decision-making reflects a lack of competency. Not one of these people stood for council expressing any interest in efficiently run sewage systems.

This begs the question of why such people stand for councils? They have no interest in the core services, instead they see council as an opportunity to implement their social agendas. The system has been taken over and is being abused.

Currently, the National-led coalition Government is working on legislation to prioritise a back-to-basics approach. The intention is vitally important, but it will need to overcome the political ideology of the people already embedded into councils to action the proper implementation. Benchmarking targets will expose the failure to carry out changes, but only to the extent that the figures are not fudged. To be blunt, I have seen the fudging at first hand. I fully expect many current councillors to work with staff to undermine the intention of the legislation.

(b) Chief executive

Council management is led by a chief executive (CE) employed by the councillors. This should mean the CE is answerable to councillors and therefore accountable to the public. However, there are three weaknesses with the current arrangement.

The CE is employed collectively by councillors, so individual councillors have no authority over the CE. This is good for bad councillors and bad for good councillors. There is a self-preservation interest for the CE in dividing councillors and siding with the majority.

The CE is usually on a five-year contract, so real control is extremely limited. The Local Government Act sets the rules for the CE, but does not set a minimum contract, only a five-year maximum, after which the requirement is merely for the position to be readvertised. A good CE can be reappointed after the advertisement. It would therefore make more sense for a rolling one-year contract to keep the CE responsive to the councillors. The default to five years is based on advice from a gravy train made up of a small group of roving external consultants advising most councils. They are typically former council staff and are appointed to consultant panels on high hourly rates by CEs.

The CE also has responsibility for managing a number of controls over councillors, including a code of conduct. This makes for an unusual employer-employee relationship where the employee is not immediately accountable to individual councillors while having some considerable power over them.

(c) Managers

As noted in the BACKGROUND chapter, councils are fundamentally engineering and property management companies. A brief glance at elected representatives across councils reveals kindergarten teachers, a bar maid, student activists who have never held real jobs, a preponderance of Māori-first separatists, union agitators and cycle advocates. It should not come as any surprise that decision-making reflects a lack of competency. Not one of these people stood for council expressing any interest in efficiently run sewage systems.

This begs the question of why such people stand for councils? They have no interest in the core services, instead they see council as an opportunity to implement their social agendas. The system has been taken over and is being abused.

Currently, the National-led coalition Government is working on legislation to prioritise a back-to-basics approach. The intention is vitally important, but it will need to overcome the political ideology of the people already embedded into councils to action the proper implementation. Benchmarking targets will expose the failure to carry out changes, but only to the extent that the figures are not fudged. To be blunt, I have seen the fudging at first hand. I fully expect many current councillors to work with staff to undermine the intention of the legislation.

(b) Chief executive

Council management is led by a chief executive (CE) employed by the councillors. This should mean the CE is answerable to councillors and therefore accountable to the public. However, there are three weaknesses with the current arrangement.

The CE is employed collectively by councillors, so individual councillors have no authority over the CE. This is good for bad councillors and bad for good councillors. There is a self-preservation interest for the CE in dividing councillors and siding with the majority.

The CE is usually on a five-year contract, so real control is extremely limited. The Local Government Act sets the rules for the CE, but does not set a minimum contract, only a five-year maximum, after which the requirement is merely for the position to be readvertised. A good CE can be reappointed after the advertisement. It would therefore make more sense for a rolling one-year contract to keep the CE responsive to the councillors. The default to five years is based on advice from a gravy train made up of a small group of roving external consultants advising most councils. They are typically former council staff and are appointed to consultant panels on high hourly rates by CEs.

The CE also has responsibility for managing a number of controls over councillors, including a code of conduct. This makes for an unusual employer-employee relationship where the employee is not immediately accountable to individual councillors while having some considerable power over them.

(c) Managers

Council managers, at both the general manager and department manager level, are insulated from voters (governance) and ratepayers (customers), with no clear publicly reported measures of performance. As a result, they appear focused on the process rather than the outcome. So long as the process is followed, they can defend bad outcomes, such as mistakes and failures. This means the process doesn’t get fixed.

Processes are administrative tasks. While they may be based on a series of checks and balances along the way to prevent mistakes, the practical reality is that each approval step is carried out by someone looking at an isolated issue, not the end-to-end delivery, voiding them of responsibility.

Success is achieved by ‘yes’ votes from councillors to accept reports and proposals, because that removes responsibility from the manager. To do that, managers tailor reports to obtain the desired decision, leaving councillors misinformed or uninformed. The result of this blinkered process is poor outcomes – which clearly points to a failed process, yet the process is never questioned.

(d) Staff

There are certainly many good people working for councils and it is simply unfair to tar them all with the same brush. It is equally unfair to pretend that all council employees are faultless. When exposed to complaints, a former chief executive of Hamilton repeatedly claimed he had 100 per cent confidence in his staff. This is mathematically and evidentially blatant mismanagement. He had 1,400 staff, so even if just one per cent made one mistake per year, that is 14 mistakes in need of fixing. I regard myself as a highly skilled and experienced professional, and I make far more mistakes than that every year. The chief executive failed his duties by refusing to acknowledge errors and he was active in covering them up.

The fact is mistakes should be expected. It is human. Admitting them is part of the solution. Covering up means mistakes not only don’t get fixed – they get systematised and repeated.

The lack of accountability should eliminate the fear of admitting mistakes because there are no consequences. Perversely, the opposite is true. The lack of accountability also manifests in an absence of measures for good performance. Employees with good track records, who make occasional errors, feel safe knowing their value outweighs the negatives. Without performance measures, having to admit a mistake is the only consequence and there is nothing to offset it, therefore it becomes the problem to be avoided.

This also leads into task isolation, sometimes called a silo mentality. A staff member given a goal of raising parking revenue will install more parking meters in the central business district. Payments and fines may increase but so do collection and maintenance costs. As frustrated customers abandon the city centre for suburban malls, rates income drops by more than the parking revenue increase. The council is worse off but the staff member has done a ‘good’ job. Management will not admit the mistake.

Silo mentality grows into empire building. Council planning departments have expanded regulations, then expanded staff numbers to manage the regulations, then the new staff expand regulations in a cycle that strangles development.

Another common feature of bureaucracies is the Peter Principle derivative known as the Dilbert Principle (named after the cartoon). This states that in large organisations people rise to their level of incompetence. A competent person will get promoted as a reward, rising up through the ranks. However, when the person is evidently no longer competent at the complex tasks of a current role, he or she will not get any further promotions and will be stuck in the incompetent role.

Finally, we must consider what type of person chooses to work for councils. It is a simple truth that people with creativity and initiative will avoid bureaucratic organisations. Others will use council positions as stepping stones to a career outside council – those with ‘get-up-and-go’ will get up and go. Without doubt, some people have seen councils as a position of authority and a resource to use for their social agendas. The lack of accountability protects them and gives freedom to spend other people’s money. Once ensconced, they employ like-minded people. There has been a fundamental and coordinated culture shift in councils over the last decade that is not working for ratepayers.

This is the third part of a series. Part A is here and part B is here.

Andrew Bydder is a is a Hamilton City Councillor, a professional problem solver, a designer, and a small business owner. This article was first published HERE

1 comment:

It does not help that the public now generally do not know what is going on. I came from a provincial town and Council activities were reported in the local delivered free paper. But that now gone. Few get the major dailies and Council matters are very inadequately coverd anyway, and then far from objectively. In Auckland Council delivered a news sheet of sorts but that now not delivered and restricted to entertainment events.The public disconnect has opened the field to minority single self interest pressure groups, including maori.The latter possess powers of cancellation which dominates all other councillors and stymy any motivation they had for the general interest.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.