Love him or hate him, Trump is changing the world

What happened in Venezuela overnight is still unfolding, and while I have some baseline knowledge of the country’s long socialist collapse, its role in global narcotics trafficking, and the fact that it is sitting on a shit tonne of oil, I found myself feeling very disoriented about what the hell was happening. As it is an unfolding event, it is precisely the sort of moment where half-baked hot takes, tribal loyalty, and reflexive moralising are not at all helpful.

So I am going to try to avoid all of that and focus on trying to work through the legal and political consequences as well as lay out some possible motivations in a way that hopefully helps us figure out what’s going on. I will acknowledge any of my own opinions along the way.

In the early hours of January 3, residents of Caracas reported explosions, low-flying aircraft, and smoke across parts of the city. Reuters journalists confirmed blasts beginning around 2am local time and lasting roughly 90 minutes, with video circulating online showing flashes and heavy smoke. Venezuelan authorities say both civilian and military installations were struck in Caracas and nearby states. A national emergency was declared and mobilisation ordered.

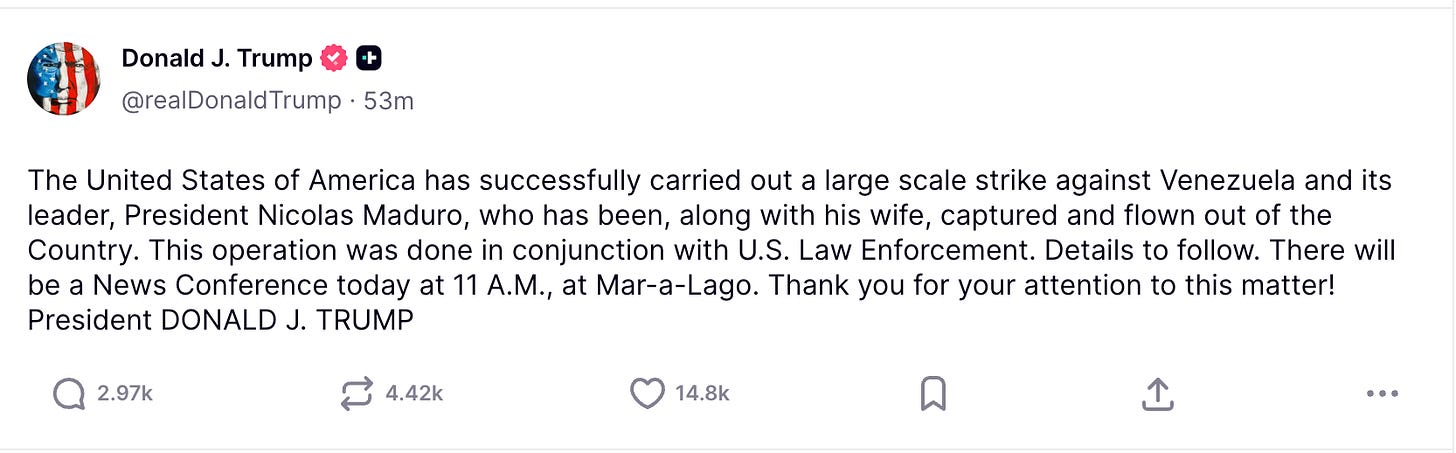

Donald Trump has stated that the United States carried out a “large-scale strike” and that Venezuela’s illegitimate president, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Cilia Flores were captured and removed from the country.

Donald Trump has stated that the United States carried out a “large-scale strike” and that Venezuela’s illegitimate president, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Cilia Flores were captured and removed from the country.

Click to view

As is inevitably the case, this strike did not emerge in a vacuum. In the months leading up to this strike, the United States stepped up pressure on Venezuela through a combination of counter-narcotics operations, increased maritime interdictions, and renewed emphasis on long-standing US criminal allegations against Nicolás Maduro and senior regime figures.

The allegations are not new though. Since March 2020, the US Department of Justice has accused Maduro of narco-terrorism and offered rewards for information leading to his arrest. Later under Joe Biden’s administration, the rhetoric softened, but he did not withdraw the 2020 indictments nor the rewards. It is also worth noting that the charges were brought by the Department of Justice and prosecutors operate independently of the White House.

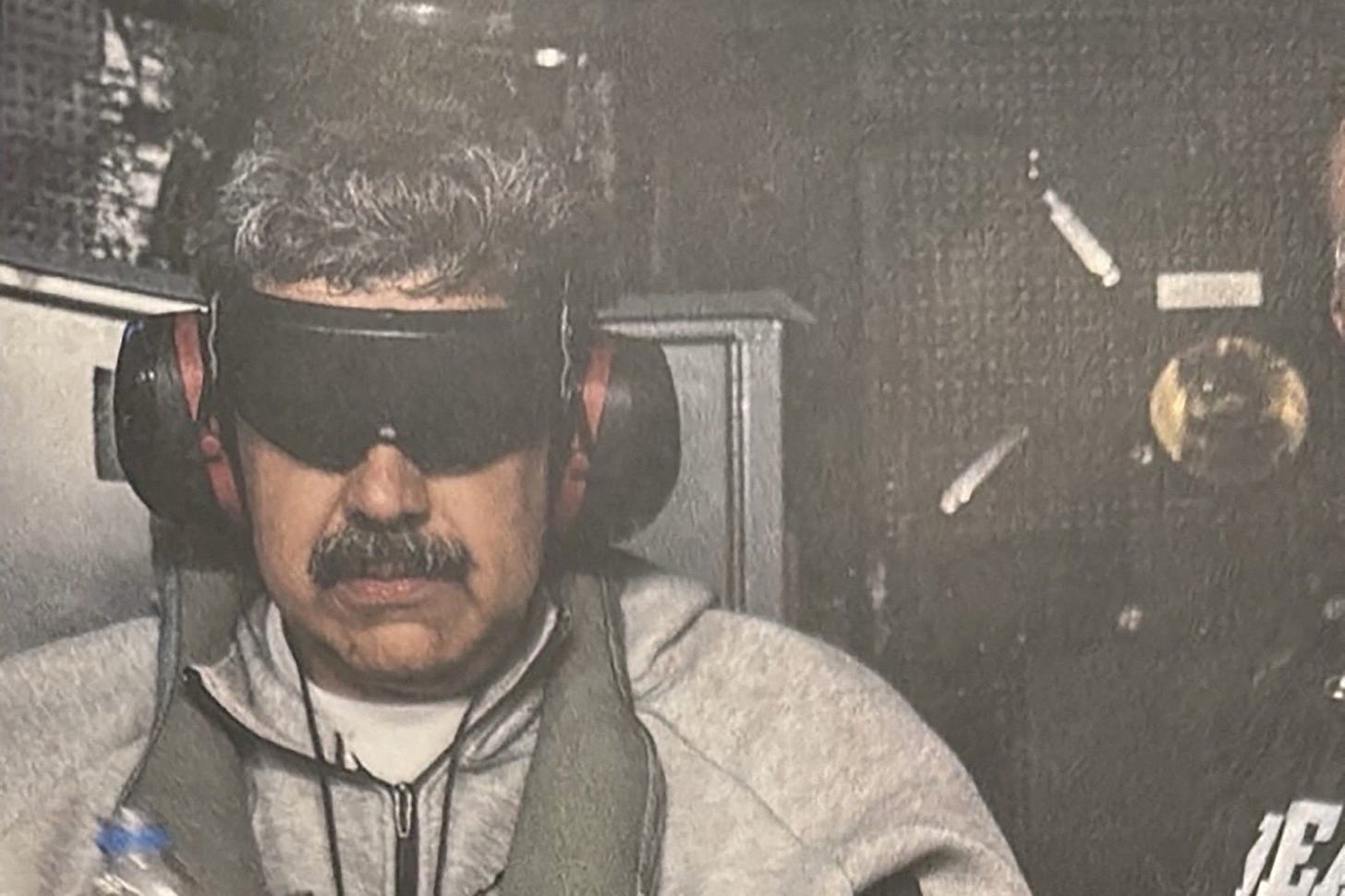

Nicolás Maduro en route to the US

With Maduro in US custody, the legal, diplomatic, and geopolitical implications are enormous. This is far, far bigger than “a strike” or sanctions. This is a whole other category of action. It is the forced removal or detention of a sitting head of government by a foreign power. Even though there is widely accepted evidence that he lost the 2024 election and simply installed himself as leader.

How will this play out and what will various stakeholders do?

Legally, the first thing opponents will point to is sovereignty. Using force inside another state’s territory is presumptively unlawful unless it fits a narrow set of justifications which include UN Security Council authorisation, self-defence against an armed attack, or (more controversially and problematic) consent by the host state. A “counter-narcotics” or “law enforcement” justification is not likely to meet that high bar. We are already seeing the operation being treated by many states, and not just adversaries, as a precedent-setting breach. For a powerful country to claim the right to bust into another country, seize its leader, and call it policing is be a massive departure from the rules based order that has roughly existed since the World Wars.

Some commentators argue that this is not actually a departure from modern norms at all, but a return to a pattern the United States has followed before. They point to the killing of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011, carried out without Pakistani consent and justified on the basis that sovereignty cannot be used as a shield for transnational criminal or terrorist activity. They also cite the 1989 US invasion of Panama and the capture of Manuel Noriega, a sitting head of government indicted on drug trafficking charges and treated explicitly as a criminal defendant rather than a protected sovereign. Even further back was the 1983 invasion of Grenada which showed the same pattern of the US acting unilaterally in its hemisphere, outside UN authorisation, to remove a regime it judged dangerous or illegitimate, and then daring the international system to stop it. In each case, Washington either rejected or heavily qualified the idea that international law imposed an absolute constraint on action.

What feels shocking now is not the action itself but the erosion of the polite fictions that usually surround it. Historically, the US has at least created (arguably) a pretence to justify their action eg “weapons of mass destruction”. Taking this view, Venezuela is not a norm-breaking escalation but an unusually candid application of an existing doctrine, one stripped of the comforting euphemisms that typically soften public reaction. If that is right, the real change is not in American behaviour, but in the willingness of the US to act openly, without pretending that international law alone is the ultimate arbiter of power in a system that has never truly operated that way.

And boy has Donald Trump been open.

Another matter of contention is the fact that sitting heads of state generally have immunity from foreign criminal jurisdiction (with narrow, highly contested exceptions). This is to ensure that everyone doesn’t just start kidnapping each others’ leaders willy nilly. The US position is “we have an indictment,” and “Maduro isn’t legitimate,” so “we don’t recognise him.” They are effectively arguing that means he doesn’t get the protections that come with office.

Head of State immunity is not an absolute shield against criminal responsibility, particularly where a leader is accused not of policy-related crimes but of operating a transnational criminal enterprise. The US says Maduro is not being treated as a sovereign equal engaged in lawful state activity, but as the head of a regime that has, for years, fused state power with organised crime, narcotics trafficking, and terrorism-related conduct that directly harms other states. They argue that rather than “kidnapping leaders willy-nilly,” being the precedent set, their action could dismantle the corruption sheltered by personal immunity for leaders accused of the most serious crimes. The US not recognising Maduro as the legitimate president, is not stripping him of protections then, but declining to confer them in the first place.

That is undeniably political, but international law has always been entangled with recognition politics. Who ‘we’ recognise is no small matter. Think Palestine, Taiwan, and Somaliland. From this perspective, the threat to stability does not come from challenging immunity, but from allowing leaders to weaponise sovereignty as permanent protection for criminal conduct that crosses borders and corrodes the international order itself.

Diplomatically, this situation forces all states to now choose how far they’re willing to go in either legitimising or condemning the US. Countries that dislike Maduro, and his actions, still have to think about the precedent the actions set. There will be a predictable split between US allies who will support Washington’s narrative (especially if framed as counternarcotics/anti-corruption), states that will condemn on sovereignty grounds, and a large group that will fence-sit, calling for “restraint” and “dialogue”, while hoping they won’t be forced to take an actual position. We are seeing this already.

Head of State immunity is not an absolute shield against criminal responsibility, particularly where a leader is accused not of policy-related crimes but of operating a transnational criminal enterprise. The US says Maduro is not being treated as a sovereign equal engaged in lawful state activity, but as the head of a regime that has, for years, fused state power with organised crime, narcotics trafficking, and terrorism-related conduct that directly harms other states. They argue that rather than “kidnapping leaders willy-nilly,” being the precedent set, their action could dismantle the corruption sheltered by personal immunity for leaders accused of the most serious crimes. The US not recognising Maduro as the legitimate president, is not stripping him of protections then, but declining to confer them in the first place.

That is undeniably political, but international law has always been entangled with recognition politics. Who ‘we’ recognise is no small matter. Think Palestine, Taiwan, and Somaliland. From this perspective, the threat to stability does not come from challenging immunity, but from allowing leaders to weaponise sovereignty as permanent protection for criminal conduct that crosses borders and corrodes the international order itself.

Diplomatically, this situation forces all states to now choose how far they’re willing to go in either legitimising or condemning the US. Countries that dislike Maduro, and his actions, still have to think about the precedent the actions set. There will be a predictable split between US allies who will support Washington’s narrative (especially if framed as counternarcotics/anti-corruption), states that will condemn on sovereignty grounds, and a large group that will fence-sit, calling for “restraint” and “dialogue”, while hoping they won’t be forced to take an actual position. We are seeing this already.

“The UK has long supported a transition of power in Venezuela. We regarded Maduro as an illegitimate president and we shed no tears about the end of his regime…I reiterated my support for international law this morning,” British Prime Minister Keir Starmer said.

“New Zealand is concerned by and actively monitoring developments in Venezuela and expects all parties to act in accordance with international law. New Zealand stands with the Venezuelan people in their pursuit of a fair, democratic and prosperous future,” New Zealand Foreign Minister Winston Peters.

“We urge all parties to support dialogue and diplomacy in order to secure regional stability and prevent escalation. We continue to support international law and a peaceful, democratic transition in Venezuela that reflects the will of the Venezuelan people,” Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

“A very serious affront to the sovereignty of Venezuela and a extremely dangerous precedent to all the international community,” Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

“Freedom advances. Long live freedom, damn it!” Argentinian President Javier Milei.

"The government believes that external military action is not the way to end totalitarian regimes, but at the same time considers defensive intervention against hybrid attacks on its security to be legitimate, as in the case of state entities that fuel and promote drug trafficking," Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni.

“The Venezuelan people are today rid of Nicolás Maduro’s dictatorship and can only rejoice. By seizing power and trampling on fundamental freedoms, Nicolás Maduro gravely undermined the dignity of his own people.

The upcoming transition must be peaceful, democratic, and respectful of the will of the Venezuelan people. We wish that President Edmundo González Urrutia, elected in 2024, can swiftly ensure this transition,” French President Emmanuel Macron.

“The EU is closely monitoring the situation in Venezuela… The EU has repeatedly stated that Mr Maduro lacks legitimacy and has defended a peaceful transition. Under all circumstances, the principles of international law and the UN Charter must be respected. We call for restraint,” High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas.

The defence of the so-called “rules-based order” that many Western countries have quickly jumped to, is understandable if a little rich. Americans are quite right to point out that the rules-based order has only been able to be maintained thanks to the threat of powerful military force from the United States. They have formed the backbone of the West’s defence against tyranny and attack. They have compensated for the alarming weakening defence capabilities in other countries and have propped up NATO.

China, Russia, and Iran have not been deterred from pursuing expansionist agendas because they believe in and want to protect a rules-based order. They have held back because the threat of the USA dealing to them has been ever present.

On the US domestic side, there will be a constitutional and institutional crisis and one that is likely to be played out in a very partisan manner. Congress will be forced to confront war powers questions, oversight of the operation’s authorisation, and the legal posture of holding a foreign head of state captive/on charges. This will no doubt become a long, messy collision of criminal law, foreign policy, and constitutional authority.

The Democrats are already tying themselves in knots over the situation. On the one hand, they agree that Maduro is “an illegitimate leader” but then claim that Venezuela is “a sovereign foreign nation”. They predict that this will “destabilize the region” and they are likely correct, but the region was hardly a beacon of stability in the first place. On top of this, Joe Biden granted approximately 600,000 Venezuelans asylum in the United States due to the suffering they were experiencing in “the region”.

“Donald Trump has, once again, shown his contempt for the Constitution and the rule of law. The President of the United States does NOT have the right to unilaterally take this country to war, even against a corrupt and brutal dictator like Maduro,” Senator Bernie Sanders.

President Trump’s unilateral military action to attack another country and seize Maduro — no matter how terrible a dictator he is — is unconstitutional and threatens to drag the U.S. into further conflicts in the region,” Senator Elizabeth Warren.

“Venezuela is ruled by an illegitimate regime, but the Administration has not made the case that an urgent threat to America’s national security existed to justify the use of U.S. military force. President Trump has made no secret of his intentions to effectively abolish the Congress, and that pattern continues today with his flagrant disregard for the Article One war powers of Congress which is essential to our constitutional system of checks and balances,” Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi.

Even without attributing support or opposition to the actions of the US, it cannot be disputed that this is a watershed moment. Donald Trump is explicitly demonstrating the military might and incredible strategic and intelligence capabilities of his country.

Objectively, it is astounding just how surgically precise the operation appears to have been. If the reports are accurate, US forces were able to locate, isolate, and remove Nicolás Maduro in a matter of hours, by penetrating one of the most security-saturated environments in Latin America, and exit without large-scale civilian casualties, urban devastation, or prolonged fighting. That stands in stark contrast to the grinding, destructive interventions of the early 2000s, Iraq being the prime example, where regime removal was achieved through overwhelming force, mass displacement, years of insurgency, and ultimately state collapse. Here, the strategic objective was narrowly defined and apparently achieved without flattening cities or triggering immediate humanitarian catastrophe.

For supporters of the operation, this is evidence that the US has learned from its worst mistakes and has prioritised intelligence over brute force and speed over mass mobilisation. Whether the downstream political consequences prove manageable is still an open question, but as a piece of military execution, many are arguing that this represents a fundamentally different, and far more restrained, model of using force than the disasters people instinctively compare it to.

The implications are huge nonetheless. The capture of Maduro forces decisions about sovereignty, immunity, legal authority, recognition, succession, retaliation, and precedent, all at once, in public, under pressure, with incomplete information. It changes the perception of the rules everyone thinks they’re living under. Even states that privately want Maduro gone are asking themselves what this means for their security. There is potential that this makes the entire international environment more paranoid and more combustible.

Howeve, any attempt to understand Donald Trump’s motivations has to look at it not from the point of view of whether this action is wise or lawful or morally right, but why it would make sense to him politically, strategically, and narratively.

President Donald Trump speaks at Mar-a-Lago on Saturday, Jan. 3, 2026

At the most basic level, Trump is instinctively drawn to actions that are decisive, visible, and difficult to unwind. He has shown that he has little faith in the utility of quiet strength demonstrated through diplomatic process or slow choreography. He prefers to demonstrate strength through action, forcing outcomes, and compelling others to respond. He sees this willingness to escalate quickly, act unilaterally, and ignore institutional hesitation as a way to communicate deterrence effectively. Trump has long subscribed to the idea that unpredictability is a strategic asset.

Some critics might comment that Venezuela occupies a particular symbolic place in Trump’s worldview. The issue encompasses several of his core ‘pet’ themes including drugs, border security, socialism, and American decline. They might also point to Venezuela as an unresolved score from Trump’s first term as he openly backed regime change, but was not successful. They will say that sovereignty has been violated in an attempt at regime change by force with legal justifications retrofitted after the fact. They’ll frame the attack as imperial aggression motivated by resource control rather than justice.

But beyond the personal there are some key reasons why the United States might take this action. One of the clearest underlying drivers is a long-standing US belief that the Americas form a shared security ‘neighbourhood’, where the presence or influence of hostile outside powers is treated as a direct concern. This was laid out in the Monroe Doctrine which Trump is now calling the Don-roe Doctrine. It is a long-standing US foreign-policy principle dating back to 1823, which holds that the “Western Hemisphere” constitutes a distinct security sphere in which external powers should not establish military or political control. Because of this the US has historically treated sustained alignment between hostile foreign powers and governments in the Americas as unacceptable. Venezuela’s deepening ties with Iran, Russia, and China, therefore, have become a massive problem. Not because Venezuela itself is powerful, but because it provides proximity, access, and potential resources (oil) to adversaries seeking to project influence close to US territory.

It is being claimed that the US strikes also hit Iranian-linked facilities in Venezuela, including factories allegedly involved in producing ‘Shahed-type’ drones. Iran has used Venezuela for years as a logistical, financial, and operational foothold in South America, a relationship enabled and protected under Nicolás Maduro. Multiple investigations over the past decade have documented Venezuela’s role as a money-laundering hub for Iranian networks, with hundreds of millions (potentially billions) of dollars allegedly routed through the country to evade sanctions. Against that background, the reported targeting of Iranian drone infrastructure reframes the operation as a strike against Iran’s global power projection too, not merely an intervention in Venezuelan politics.

From Tehran’s perspective, this is deeply destabilising. Venezuela has functioned as a geographically distant, invaluable strategic rear base through which to gain proximity to the Western Hemisphere. If that sanctuary is no longer reliable, Iran’s ability to operate globally, fund proxies, and develop or distribute military technology is materially weakened.

A big piece of context is that Venezuela’s natural resources are extraordinary and unmatched globally. It holds the world’s largest proven oil reserves, alongside vast quantities of natural gas, gold, iron ore, coal, freshwater, and a range of strategically important minerals. This makes Venezuela not just a failing state, but a dormant energy and resource superpower whose output, or lack of it, has outsized consequences for global markets.

Analysts are predicting that effective US control or influence over Venezuelan production will materially reshape global energy dynamics. Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska has openly stated that if Washington are able to exert decisive influence over Venezuelan oil, it could help keep prices at around $50 a barrel, placing huge pressure on Russia which depends heavily on sustained higher energy prices to fund government spending and geopolitical ambition.

Others are focusing on consequences for China as they currently source a substantial share of their oil from Venezuela and Iran who have historically been less vulnerable to US pressure. With that independence potentially cut off in Venezuela and under threat in Iran, China’s strategic position changes.

Energy security underpins everything from economic stability to military planning, and any perception that supply could be constrained in a crisis forces a reassessment of risk. If the United States can exert meaningful control or leverage over a majority share of energy supply, the risk profile of any Indo-Pacific escalation reduces sharply. Energy vulnerability does not prevent conflict outright, but it raises the cost and uncertainty of sustained military action. This particular factor is of importance to New Zealand and our neighbours.

This all leads to another conclusion and one that Trump has not shied away from; that Venezuela’s significance in this moment lies less in its domestic politics than in its position as a pressure point in a much larger contest over energy, leverage, and global power.

Of course, another motivation is deterrence by example. The US is operating in a global environment where norms against force are already eroding. Russia has invaded Ukraine, Iran uses terroristic proxies, and China tests limits constantly and incrementally. In that context, there is reasonable concern that restraint could be read not as good diplomacy and stable leadership, but as permission for hostile powers to push their luck. Acting decisively in a relatively isolated location like Venezuela may be seen by the US as a way to reassert credibility, show that some red lines still exist, and make it really clear that alignment with US adversaries carries tangible costs.

Timing is a key factor too. The US will have assessed that the current risk for Venezuela’s allies to get involved is low(er). Russia is fighting a war in Ukraine, China is playing warship theatre around Taiwan and is risk-averse about overt confrontation in the Americas in any case, and Iran is now distracted by a building peoples’ revolt domestically. None are likely willing to escalate militarily over Venezuela in these circumstances. But that does not make the action consequence-free; it just lowers the probability of immediate retaliation. Strategic windows like this are rare, and states that believe a problem is festering tend to act when the costs of inaction appear to be rising faster than the risks of intervention.

In the aftermath of the operation there has been striking contrast between elite commentary and Venezulan and diaspora reaction. While legal academics, media, and politicians debate sovereignty, precedent, and international norms, many ordinary Venezuelans are responding with pure joy and relief. For them this represents new hope and the possibility that they will suffer no longer under tyranny and depriivation.

For those who fled Venezuela after years of violence, kidnapping, and state-linked criminality, the events are not seen as an academic violation of sovereignty but as a moment of long overdue justice. Across America, Venezuelan immigrants have poured into the streets celebrating the news.

None of this resolves the legal questions. But it does complicate the moral story. When those most directly harmed by a regime respond with relief rather than fear, it exposes a gap between how power is analysed in theory and how it is experienced in practice.

My opinion:

I have tried to lay this all out as evenhandedly as possible, and without arguing too much of a perspective. The US action may yet prove reckless. It may destabilise Venezuela further and could entrench authoritarianism under a different face. It could backfire strategically. But, I also think it is crucial for the stability of the world that Western governments, media, and populations set aside any Donald Trump Derangement Syndrome and assess the risks and benefits to our collective future before reflexively opposing the action. It may be (or not) that the we would have opposed the action if told about it in advance, but now that it is done moral posturing is far less important than securing future peace and stability. Siding with Iran, Russia, and China will not do anything but speed up the demise of Western liberal democracies. Frankly, it would be an extraordinary act of self-harm.

I don’t say any of this because I have expertise in assessing whether the US has made the right call. I say it because pretending this can be analysed through memes and moral sloganeering is very dangerous. This is a complex and multi-faceted geopolitical challenge and it should not be determined by elites picking sides because they love or loathe Donald Trump. This is way, way too important for “orange man bad” bullsh*t. He may be bad, or he may be the second coming, but a world in which the US is not powerful enough to protect the West from the tyranny, oppression, and violence advanced by Iran, Russia, and China would be very bad indeed.

Ani O'Brien comes from a digital marketing background, she has been heavily involved in women's rights advocacy and is a founding council member of the Free Speech Union. This article was originally published on Ani's Substack Site and is published here with kind permission.

17 comments:

I can think of the 2014 coup in Ukraine sponsorship by Obama/ Biden. The overthrow of Gaddafi orchestrated by Obama/Biden. The overthrow of Assad orchestrated by Biden/Harris. US doing this stuff is fairly common.

Wow, I can’t believe a Republican president did what the last 3 Republican presidents did and sent the USA into a recession and then started a war with another country for oil!

Thank you Ani. Your thoughtful articles on contentious/controversial matters are eagerly read and most appreciated.

My 2 year old nephew is also “drawn to actions that are decisive, visible, and difficult to unwind”.

Great article Ani, truly informative and very much appreciated - thank you.

Ani - in your well presented article, I did see nor read anything about "how" Maduro 'came to power', the acts of both terror and violence (actively carried out by both Police & Military Units) upon those who both resisted & protested about the electoral process at the time. Nor did you mention recent elections where the "People" voted for someone else to become President, only to have Maduro "overthrow' that result.

As a result of Maduro's 'reign' (both times) that the People of Venezuela have suffered both economically and practically, i.e. scarcity of food and other factors for maintaining a life.

Maduro & his wife, along with the Maduro sycophant's, have not suffered, odd that.

Your article does not cover the Drug Lords (who have bankrolled Maduro) who also aided & abetted the movement of drugs into America. Something that The Democrat Party (for the periods they held political sway in both Washington D.C and what is called " the blue states") failed to both contest or actively work to eradicate - California would be a classic example.

It is also a considered opinion, that Maduro actively supported the movement of People both from Venezuela & other Central American Countries, as well as those from other Nations (my example being Africa) toward the American / Mexican Border.

This last factor, the stopping of such 'traffic' was started by Trump in his first term, and in his current term has certainly 'fixed the problem', which many US Law Agencies have stated it has affected the movement of drugs into America. Along with the 'riff raff' who became a minor issue with crime in many American Cities.

Also, Ani, are you aware that Maduro had placed into the hands of Iran an island, off the coast of Venezuela that became the training base for both Hamas & Hezbollah, for which it is alluded that Venezuela Military provided both training and logistical assistance?

Yup, as of today we have had two New Zealand Academic's 'ring their hands on National radio news', more over the Trump Factor, and they to seem to miss what the "removal of Maduro" will do for Venezuela, for which International News shows that they both celebrate Maduro's removal and thank Trump for what he has done.

Wow they got Maduro - from a different country, mind you - in 3 hours, but still haven’t gotten any of the Epstein offenders. Weird, huh? And Trump pardons drug traffickers?

Trumps actions being assessed based on his personality as MSM do is becoming really annoying .

Thank you Ani and Anonymous 10;06 am for your knowledgeable and well researched contributions to this complex topic.

Maduro was a brutal ruler, it’s true. So is Putin, who Trump supports. So was Bolsanaro, who Trump supports. So was the drug trafficking former head of Honduras, who Trump supports…and just pardoned. So is Bukele of El Salvador, who Trump supports.

Stop saying Trump cares about brutality or illegitimacy. If you think this has to do with anything but oil, you’re either an idiot or someone working at a bot farm.

US is looking after their own interests- always and by any means. The methods reflect the leader of the day personality, but the objective is the same.

Colombian President Gustavo Petro: "A clan of pedophiles wants to destroy our democracy. To keep Epstein's list from coming out, they send warships to kill fisherman and threaten our neighbour with invasion for their oil.”

Any sign of the unredacted Epstein files then?

Ani -- you mention Internatinal Law several times. What is this International Law, what does it say, who are the signatories agreeing this is International Law, who are the executors of this Law and where is it kept ? Why was this Law, if it acutally exists, not used against Putin invading Georgia, Ukraine etc and why would China not be quilty of breaching this Law (if it exists) in invading Taiwan ?

Fred H must have a problem with Google and/or Wikipedia. A few taps on the keyboard and answers to all his questions will be staring him in the face.

In a nutshell, international law consists mainly of treaties (these may have other names such as conventions) between nations. They are not contracts because, while they specify rights and obligations, they do not abide by the principle of quid pro quo. They are entirely voluntary (although many a 'peace treaty' involves a bit of arm-twisting) but nations are advised to abide by their agreements or they will gain a reputation for being untrustworthy. There are no enforcement mechanisms except voluntary ones (in which case we have an oxymoron). There are however international courts such as the International Court of Arbitration that aggrieved nations can appeal to although all those can really offer is moral support. The big powerful players such as the US and China violate international law all the time because they can get away with it, and ignore the international courts.

Environmental treaties/conventions involve making promises and keeping them about the environment e.g. pollution. Human rights treaties and conventions are a bit different in that they involve a country making promises about how it will treat its own people and foreigners within its jurisdiction.

International law is a sick joke in some ways but it offers the possibility of an international rules-based order which we badly need.

I hope this very incomplete thumbnail sketch will encourage Fred and maybe other readers to read up on international law (my own background in it is a PGDip from London).

‘The strong do what they will, the weak suffer what they must’.

I am skeptical of International Laws particularly those connected to the UN as is the US , just one of the issues being the influence of Islamists. .

The UN has a depositary for treaties, but does not act as a go-between or enforcer.

The US doesn't like international law because, being terminally self-righteous, they believe they have some sort of almost divine right to impose their law outside their own turf (extraterritorial jurisdiction). This is a constant source of friction with the EU especially with regard to companies based in Euro countries that trade with countries the US doesn't like.

I never came across any "influence of Islamists" in my studies of international law but perhaps Anon 954 could enlighten us about that.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.