The ADHD Epidemic: Disorder or Diagnosis Craze?

ADHD is having a moment. Diagnoses are exploding in New Zealand and right across the West. Waitlists are months long, private clinics are booked solid, and on TikTok, you’d think every slightly distracted middle class influencer has “finally found their answer.” Some of this is progress. Some of it is hype. And buried under the enthusiasm are a few uncomfortable truths about what a diagnosis actually means in the real world.

So why are more Kiwis being diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder? There are a few reasons. Awareness and legitimacy have finally caught up. Adult ADHD was ignored for years, especially in women. For too long, only hyperactive little boys fit the stereotype. That’s changed, and that is good.

Then… there’s the social-media factor. ADHD content floods people’s feeds; some helpful, much of it nonsense. TikTok has turned psychiatric language into personality shorthand. Suddenly every quirk is a “symptom,” and people are self-diagnosing on the back of a ten-second video. What might once have sent someone to therapy for anxiety or burnout now gets framed as a dopamine-deficiency disorder.

Then… there’s the social-media factor. ADHD content floods people’s feeds; some helpful, much of it nonsense. TikTok has turned psychiatric language into personality shorthand. Suddenly every quirk is a “symptom,” and people are self-diagnosing on the back of a ten-second video. What might once have sent someone to therapy for anxiety or burnout now gets framed as a dopamine-deficiency disorder.

Click to view

And third, in New Zealand the system itself is shifting. Until recently, adults seeking an assessment had to wait forever for a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. But from February 2026, trained GPs and nurse practitioners will be able to diagnose and prescribe for adult ADHD in New Zealand. That’s a massive change. It’ll make access easier and cheaper, but it also raises questions about consistency and standards.

The question I have been pondering over the past few years as I have watched people from all corners of my life collect their ADHD diagnoses is: are we over-diagnosing?

I have finally concluded that, yes we are, but I have some caveats. For decades, ADHD was under-diagnosed. We missed entire cohorts of people who could have benefited from support. But now we risk swinging too far the other way. Rushed telehealth assessments and “checklist medicine” are everywhere and some clinics are churning through clients at a rate of knots. Clinical rigour goes out the window in favour of raking in the available business. They hand out diagnoses like participation certificates when for the person receiving it, it feels much more meaningful.

Let me insert a caveat: I am not advocating for making diagnosis harder again. Rather it’s imperative we make it better. A proper ADHD assessment involves history from multiple sources, proof of impairment across settings, and careful exclusion of other causes like anxiety, trauma, or sleep disorders, for example. If an assessor isn’t doing that, they’re selling a label, not offering care.

Some critics argue we’re staring down a slide into psychiatric inflation. That we’ve started treating quirks, stress, or trauma responses as medical disorders. Psychologist

Dr Jessica Taylor has been prominent in this space. She’s warned that “ADHD is being over-diagnosed, and that private clinics and online services are popping up everywhere to diagnose people in minutes.” She critiques the speed and superficiality of some diagnosis mills, suggesting they trade clinical integrity for volume.

Dr Taylor goes further: she sees psychiatric diagnosis as sometimes pathologising normal human variation or distress. She describes that “mental health” is a construct, a framework we humans built to try and make sense of suffering. She also questions whether ADHD in some cases is being thrust onto people who are responding to ordinary stressors or trauma, rather than facing a discrete neurodevelopmental disorder.

She’s not alone. Sami Timimi, a British child psychiatrist turned critic, argues that the explosion of ADHD (and autism) diagnoses is partly a cultural and institutional phenomenon. He says we ask “What’s wrong with you?” instead of “What happened to you?” and medicalise responses to schooling, stress or unmet needs.

Allen Frances, once a central figure in shaping DSM diagnoses, has since become a vocal critic of diagnostic expansion. He’s repeatedly warned that we risk turning normality into pathology, that we are overdiagnosing the “worried well” while the severely ill remain under-resourced. The last part of that sentence is crucial to understanding the pressure our mental health systems are under.

These sceptical voices have empirical backing too. A scoping review of 334 studies found convincing evidence that ADHD is being overdiagnosed, especially among children and adolescents with milder symptoms. The authors warned that for these milder cases, the harms of diagnosis may outweigh the benefits.

Another review asks: Is Adult ADHD being overdiagnosed? It is a 2015 review and so predates the even more pronounced proliferation of recent years. It flags that without objective biomarkers, ADHD diagnoses depend on subjective reports and retrospective recollections, opening room for both under and over-diagnosis.

A much more recent commentary on sources of overdiagnosis lists factors like poor diagnostic practices, loosening adherence to DSM criteria, cultural shifts in how “ADHD” is used, and confusion with other conditions (e.g. anxiety, sleep disorders) as drivers of false positives.

Dr Taylor is not alone in her thesis that psychiatry is pathologising the ‘healthy’, but tramuatised. Philosophers and bioethicists have begun speaking of “hermeneutical injustice” in psychiatric diagnosis: that people can be mis-classified or treated as “sick” even when their distress is not pathological but a reaction to life circumstances or mismatch with social structures.

Another caveat! These experts and studies don’t say “no ADHD exists ever.” Instead, they push for clinical humility, restraint, and rigour. They ask: when do we help someone by diagnosing and when do we harm them by labelling?

The problem with handing out trendy diagnoses like they are just exclusive labels to add to ones social media bios, is that there are some life-changing and harmful consequences to accepting the label of ADHD. I’m not talking about medical side effects from medicines; this is about the consequences of simply being diagnosed.

That is the bit no one puts in their #ADHDawareness posts. A diagnosis can limit opportunities for the diagnosed and close important doors to their future.

Careers in the Police, Defence Force, aviation, emergency services, and some logistics or transportation roles, for example, are classed as “safety-critical.” Their medical assessments aren’t based purely on labels, but on functional risk. That means your ability to carry a firearm, operate vehicles under stress, or manage irregular hours matters, and ADHD, or the medications used to treat it, can raise red flags for recruiters.

It’s not an automatic ban, but it can mean extra scrutiny and eventual ineligibility. Someone with stable, well-managed ADHD who isn’t using prescribed stimulants, might be cleared; another person whose symptoms or side-effects could be seen to compromise safety might not. And non-disclosure, pretending you’ve never been diagnosed, can end a career faster than the diagnosis itself.

So if you, or your child, are dreaming of a badge, a uniform, or a cockpit, get clear advice before you jump into an assessment. Because once it’s on record, it’s there for life.

These careers are vitally important to society and require heavy weighting to be given to public safety over “inclusive” recruiting. There as been some outrage at what is described as “exclusion” of neurodiverse people, but looking carefully at the diagnostic criteria for ADHD it isn’t really any wonder that tough calls have to be made about who is allowed to run around with semi-automatic weapons and operate machinery with the lives of hundreds of people in their hands. I suspect most people would agree that a highly distractible person isn’t who you want flying your plane.

The fairest approach is functional, not ideological. We should assess people on what they can do safely, not on the existence of a diagnosis. But the diagnosis is instructive of what people’s behaviours are, especially abnormal behaviours. What seems to be the most important thing to avoid is misdiagnosing people who may have some quirks but don’t have ADHD. That way they won’t be limited by a diagnosis that has been liberally misapplied.

In workplaces more broadly, ADHD NZ notes that, people with ADHD may face more disciplinary processes, lower income, and challenges sustaining full-time work, though that’s likely more about performance issues or bias, not legal prohibition. While this point is not to do with overdiagnosis, the stereotypes and assumptions that are associated could well contribute to someone with a diagnosis being limited in their career.

The ADHD boom tells us something about modern life. We’re busier, more distracted, and more medicated than ever. We crave neat answers for messy realities. For some, an ADHD diagnosis is a genuine turning point that improves their quality of life. For others, it becomes an identity, a shield, or even a trap.

There’s a tidal wave of ADHD content online right now and it’s doing more than just “raising awareness”. It’s shaping minds, expectations, and diagnoses. Search TikTok, Instagram or YouTube and you’ll find hundreds of creators listing “signs you have ADHD,” “you probably have ADHD if…” or “stop ignoring this one trait.” Many of those videos pack in 10–15 bullet point symptoms (usually including: restlessness, distractibility, daydreaming, procrastinating, and impulsivity) often without context about severity, timing, other impairments, or differential diagnoses. They’re catchy. They feel relatable and accurate in that moment.

But research suggests this content is heavily misleading. In one study of the 100 most-viewed TikToks tagged #ADHD, 52% were classified as “misleading,” 27% were personal experience, and only 21% deemed “useful.” Another analysis found that fewer than half of the claims in those viral ADHD videos align with established diagnostic criteria.

Even more striking: exposure to ADHD misinformation decreases accurate knowledge about ADHD, yet increases people’s confidence in that (wrong) knowledge. This then increases intention to seek diagnosis or treatment. In other words: the more of this stuff you watch, the more sure you might be you “have ADHD,” even if your symptoms don’t match.

A related study showed that people with self-diagnosed ADHD reported consuming more ADHD-related TikTok content than those without, and they rated it as more helpful and accurate. Another found that heavy TikTok users were more likely to say the platform influenced them to seek a professional diagnosis.

Not all of this content is bad. Of course, some creators bring nuance, a wealth of personal experience, and foster healthy communities. But the algorithm doesn’t balance nuance; it amplifies what gets engagement. And sensational, oversimplified takes often win.

Celebrities with ADHD are everywhere in media headlines now, and their diagnoses are often held up in a way that is oddly aspirational. Bill Gates, Cara Delevingne, Walt Disney, Scary Spice, Emma Watson, Barry Keoghan, Robbie Williams, Jessie J, Paris Hilton, Michael Phelps, will.i.am, Busy Phillips, Greta Gerwig, Lola Young, Channing Tatum, SZA, Simone Biles, Adam Levine, Justin Timberlake, Nick Cannon, Dave Grohl, Mark Ruffalo, Nelly Furtado, Lily Allen, Beyonce’s little sister, and the most recent guy to play Spiderman are all on lists of “famous people with ADHD”.

Click to view

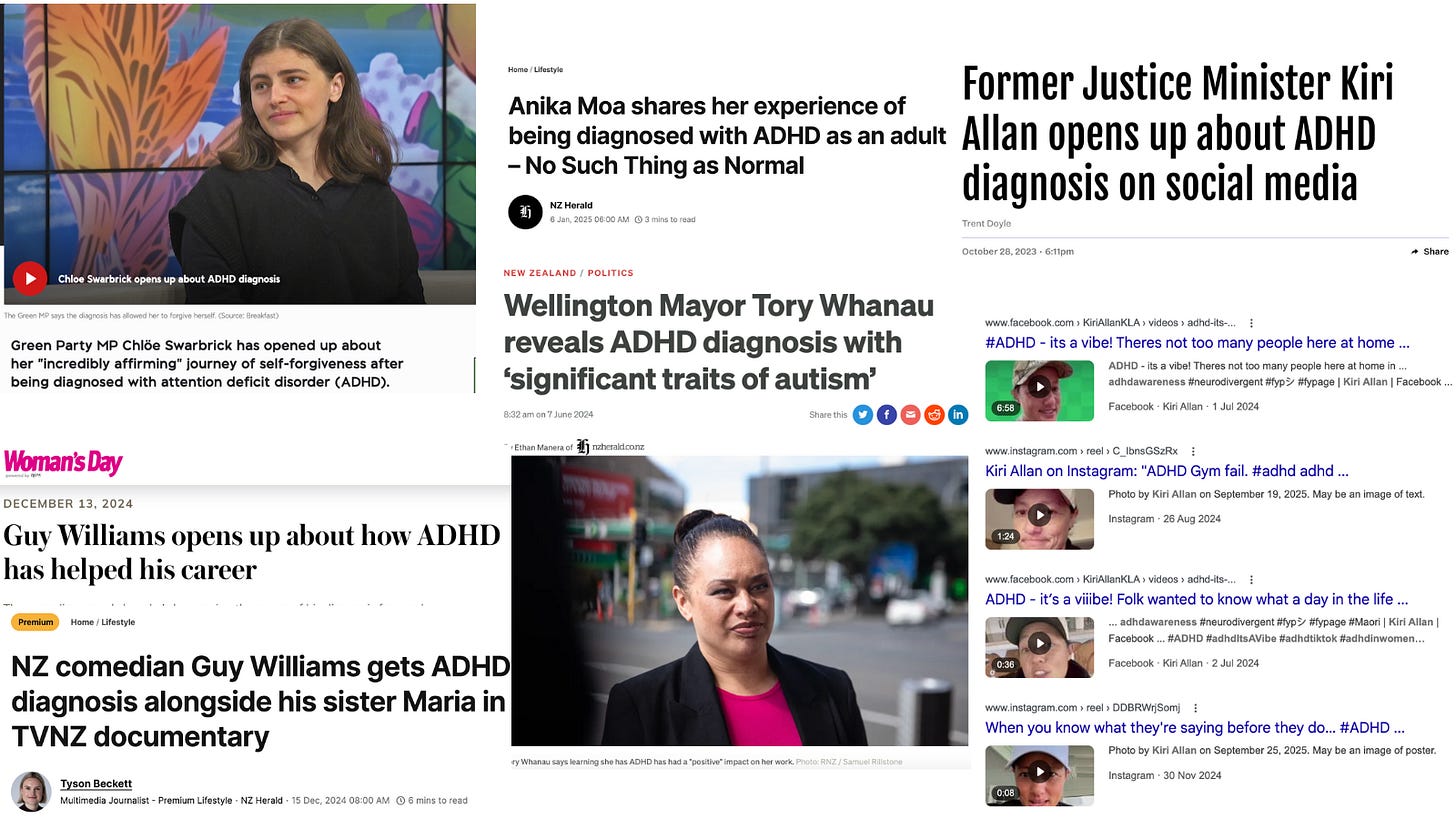

In New Zealand Guy Williams, Marlon Williams, Jazz Thornton, Hayley Holt, Anika Moa, Bree Tomasel, Sonia Gray, Matthew Ridge, Petra Baghurst, Ginette McDonald, Melanie Bracewell, Lego Masters’ Jono Samson, and a plethora of Shortland St actors have all spoken about their ADHD diagnoses. In the political world, Green Party co-leader Chloe Swarbrick is open about having ADHD and both former-Wellington Mayor Tory Whanau and former-Justice Minister Kiri Allan disclosed their diagnoses following significant public scandals.

“You know, I’ve joined the modern wave of receiving an ADHD diagnosis.” - Marlon Williams

The media love these stories. They spin them as inspiring, “look, ADHD doesn’t stop success,” or normalising “so many famous people have ADHD, it must be everywhere.” But the reports usually skip the complexity. We rarely see how the diagnosis was made, what comorbidities exist, how much functional impairment was present, or whether the celebrity was medicated or unmedicated at different times.

Click to view

Worse, celebrity disclosures may inadvertently normalize self-diagnosis. When a media outlet runs a headline like “Greta Gerwig Reveals Her ADHD Diagnosis”, readers hear a message: “if you feel this way, maybe you’re the same.” That kind of narrative has power. In the social media ADHD bubble, these stories are currency, shared, liked, reposted, intensifying the loop of “I might have it too.” And, as much as people would hate to admit it: “it would be cool to have it.”

“Put a finger down if you regularly: touch your face, make impulse purchases, have more than four tabs open on your browser, ignore texts, lose things, or run late. If you lost a whole hand, you might have ADHD. At least, that’s what some TikTokkers are telling us.”

Normal feelings, or ADHD, ASD or PTSD? Social media is here to diagnose you, The Spinoff

The online ADHD ecosystem is vast, seductive, and sloppy. It traffics in identity narratives and feels true, but lacks any creditability. When people see influencers and celebs talking about ADHD and symptom lists in 30-second videos, it becomes easy to misread normal life as disorder. In a world where diagnosis is becoming easier and more accessible, that mix of media, celebrity, and algorithmic reinforcement is a storm we need to be seriously wary of.

We needed to fix access to diagnosis, support, and treatment and we are. But a diagnosis isn’t a personality badge; it’s a clinical conclusion with medical, legal, and occupational consequences. We owe it to people to make sure that if they finally get one, it’s real, robust, and understood.

Because the question isn’t just “are we over-diagnosing?” It’s whether we’re being honest about what a diagnosis really means and who might pay the price for getting one.

Personal note: as someone with diagnosed Bipolar 1 Disorder, I would likely be excluded from working in the professions described in this piece. I accept that this is appropriate because of the nature of the work and the nature of my disorder and associated behaviour. It isn’t nice to be excluded, but we should be able to accept when it is necessary. My point is not to argue that there should not be exclusions nor that people should avoid getting diagnoses in order to avoid being excluded. The way I see it, reasonable exclusions should exist for mental health disorders and neurodevelopmental conditions and we should ensure that we avoid overdiagnosing so that those who shouldn’t be excluded aren’t handicapped by an inaccurate diagnosis.

Ani O'Brien comes from a digital marketing background, she has been heavily involved in women's rights advocacy and is a founding council member of the Free Speech Union. This article was originally published on Ani's Substack Site and is published here with kind permission.

3 comments:

One thing that's apparent is that all the NZ politicians and most "celebrities" who go public about supposedly having ADHD are left wing. Greta clearly has problems and I feel sorry for her because has been used. As for self diagnosed Tori, it's more about living in a fantasy land.

It’s bloody hard to have your own personal disorder these days , so I just blame everything on the colour of my hair , ginga as if you hadn’t guessed

I have several students with this disorder and it is very nasty. I have heard a high percentage of prison inmates have it and it has interferred with their academic achievement.

Open plan and noisy classrooms as most primary ones are is not helpful at all.

There have been studies of dietary changes that help and certainly junk food will have contributed to the problem.

It is a relational problem and some adults can manage the symptoms in a child by firm discipline.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.