The Reserve Bank doesn’t do independent fiscal forecasts so there is no news in the fiscal numbers in today’s Monetary Policy Statement themselves. The last official Treasury forecasts don’t take account of whatever the government is planning in next week’s Budget, and as the Bank notes they will need to update their assessment in light of whatever the spending and tax plans prove to be.

So I was more interested in the Bank’s numbers for the things they do forecast independently, and which in turn have implications for both the tax revenue the government could expect to collect on any given set of tax rates and for the likely expenditure pressures (from things like population growth and inflation).

One of the lines the Minister of Finance has repeatedly sought to use over her time in office is something about how much worse the economy was than they had appreciated (or had been clear) pre-election, to soften us up (it appeared) for yet more delay in getting back to fiscal surplus (see, we can’t really help it, it was done to us, and no one told us). It has always been an unsatisfactory argument (to say the least) since the previous projections (say, those in the PREFU and those in National’s fiscal plan) weren’t for a return to surplus for a couple more years anyway (2026/27) and by then whatever the forecast fiscal outcome, it is purely a matter of policy choice.

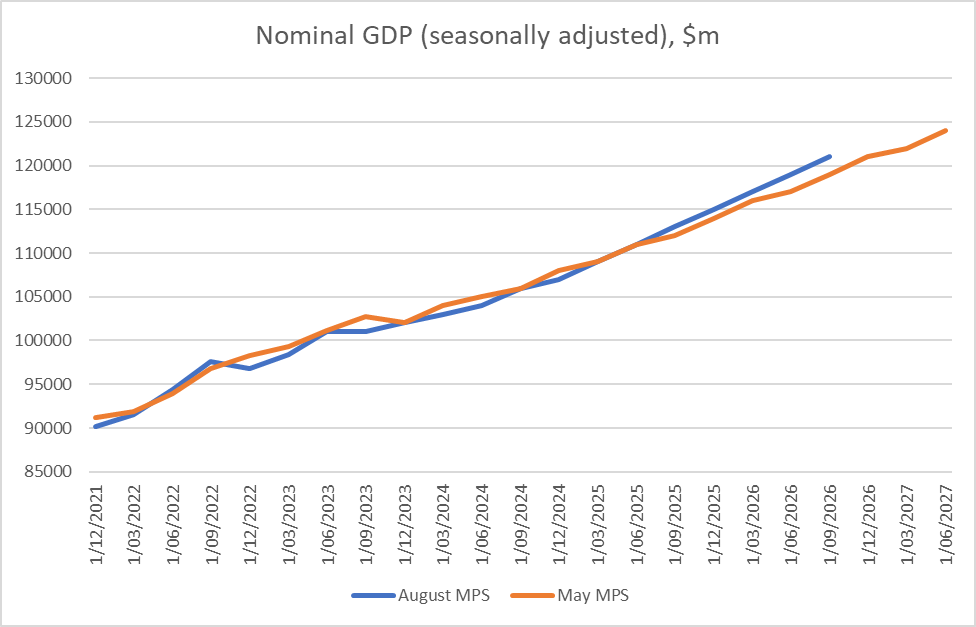

Now, the Budget numbers out next week will use The Treasury’s forecasts as their base. But here are the nominal GDP projections the Reserve Bank was making (a) at the August 2023 Monetary Policy Statement (ie the last set of forecasts pre-election), and b) today. Nominal activity is what gets taxed.

One of the lines the Minister of Finance has repeatedly sought to use over her time in office is something about how much worse the economy was than they had appreciated (or had been clear) pre-election, to soften us up (it appeared) for yet more delay in getting back to fiscal surplus (see, we can’t really help it, it was done to us, and no one told us). It has always been an unsatisfactory argument (to say the least) since the previous projections (say, those in the PREFU and those in National’s fiscal plan) weren’t for a return to surplus for a couple more years anyway (2026/27) and by then whatever the forecast fiscal outcome, it is purely a matter of policy choice.

Now, the Budget numbers out next week will use The Treasury’s forecasts as their base. But here are the nominal GDP projections the Reserve Bank was making (a) at the August 2023 Monetary Policy Statement (ie the last set of forecasts pre-election), and b) today. Nominal activity is what gets taxed.

There is a slightly larger gap opening up a couple of years out (when, of course, who knows; both sets of numbers are just anyone’s guess out there) but as late as the June quarter next year the two observations are exactly the same, as they are (a 0.1% difference) for the last pre-PREFU quarter, 2023Q2.

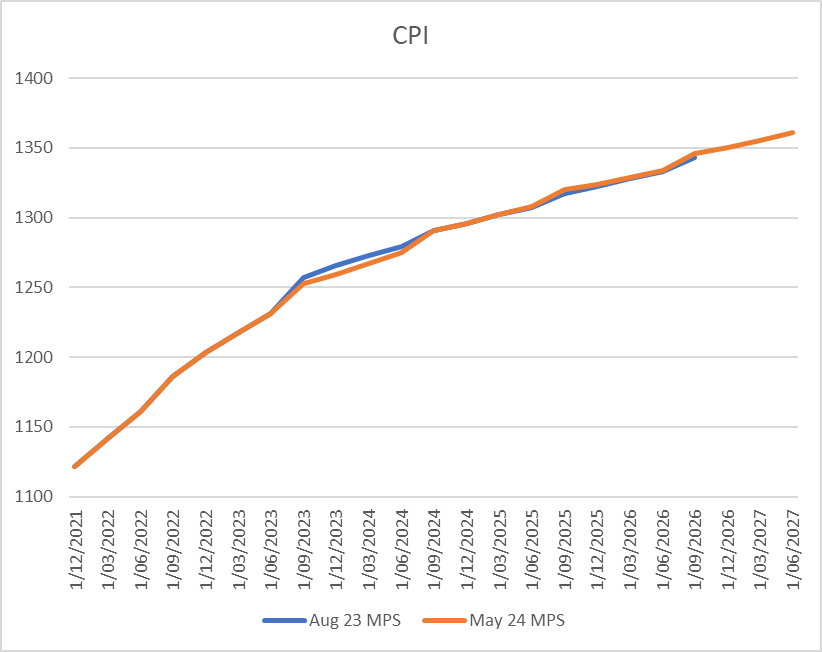

Ah, perhaps you are thinking, but what about inflation. If there is more inflation than was previously forecast the revenue just won’t go as far.

But there isn’t anything much in that sort of story either.

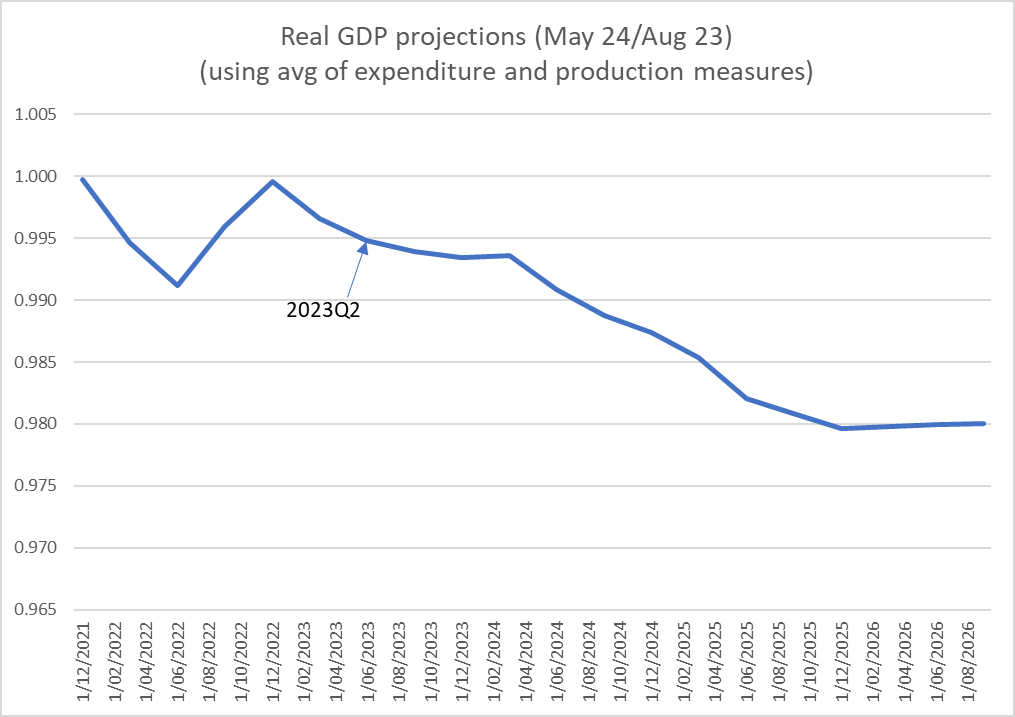

There were some historical revisions late last year to the estimated level of real GDP. Those revisions don’t have any material implications for anything much, since life had already been lived through that period, and (in any case) it is nominal GDP that more closely approximates the tax base.

But in this chart I’ve shown the ratio of the RB’s latest forecasts for real GDP to those it did last August, and it is certainly true that over the full forecast period the latest forecasts are a couple of per cent weaker than last August’s forecasts.

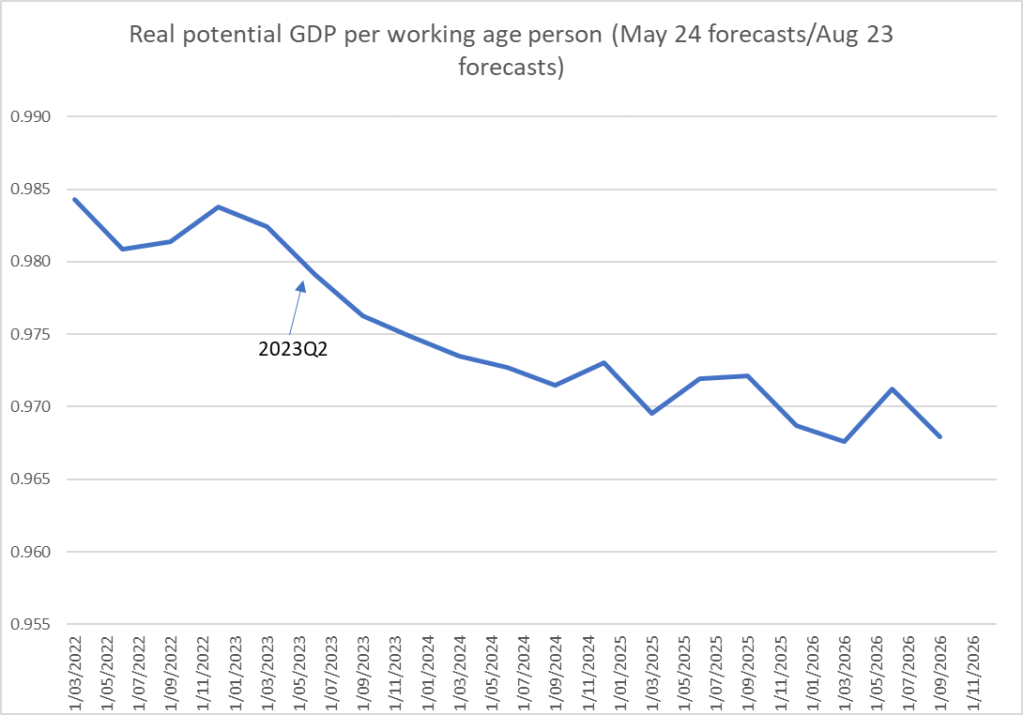

Here is a slightly more obscure chart: the same sort of ratio but this time for the Bank’s estimates of real potential GDP per working age population. Things worsen there by about 1 per cent relative to the position thought to have prevailed just prior to the election.

And if weaker GDP per person implies some loss of productivity (some things the government might be purchasing won’t be getting relatively cheaper), it also suggests that (eg) public service wage pressures and NZS adjustments should be less than they might otherwise be.

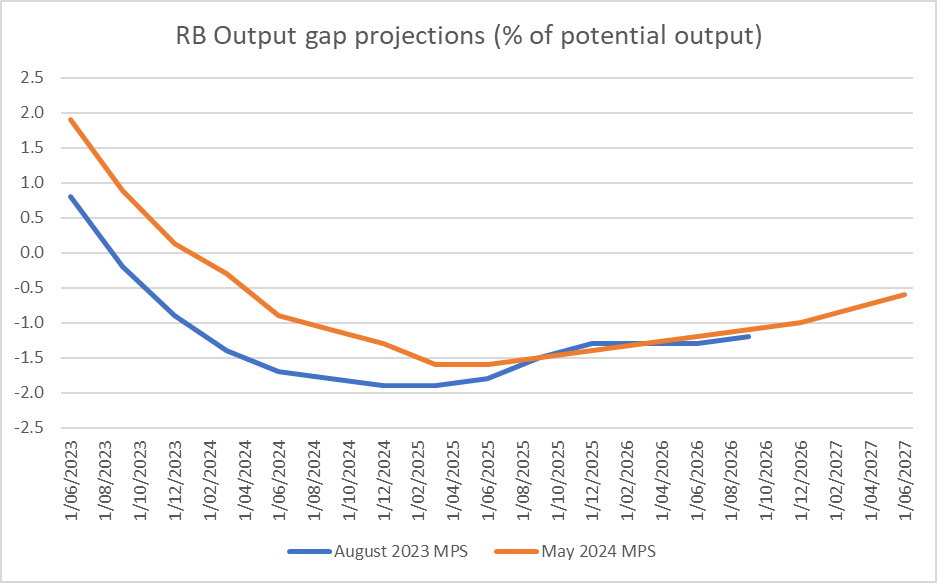

The key point? At least on the Reserve Bank’s telling – and they could of course have a very different view than the Treasury – there just isn’t that much there. We are set to be less well-off per person than the Bank thought just prior to the election, but nominal GDP and the CPI forecasts have barely changed, and even the real output changes aren’t particularly large in the scheme of things (nothing at all like the extent of the revisions that followed in the wake of the 2008 recession). What we have, on the Bank’s numbers, is a recession and a protracted period of excess capacity (slack) that is not quite as deep, but quite as protracted, as the Bank suggested to any and all readers (Opposition politicians included) just prior to the election

Michael Reddell spent most of his career at the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, where he was heavily involved with monetary policy formulation, and in financial markets and financial regulatory policy, serving for a time as Head of Financial Markets. Michael blogs at Croaking Cassandra - where this article was sourced.

1 comment:

Mr Michael Riddell. And your point is, in regard to the actual people who daily produce exports , infrastruaeture and public services for New Zealand .

I realise that the office fraternity consider they are at work but are they really pushing on the big productive wheel to make NZ progress, above the cost to run their income and graphs.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.