I can’t pretend that dinnertime on the 21st of October was anywhere near as exciting as dinnertime on the 3rd of November.

On the evening of Sunday the 3rd, I expect most of us were tuned into the final overs of the third cricket test, hoping that New Zealand would be the first to sweep a full test series in India.

By contrast, at dinnertime on Monday the 21st, I was possibly the only one in the country waiting for the embargo to lift on the Tax Foundation’s annual Tax Competitiveness report. Would New Zealand keep its third-place showing, or would Switzerland jump past us in the rankings?

There seemed little hope of catching up with the front-runner: Estonia had held top spot for a decade and was miles ahead of other challengers.

Overtaking Latvia’s much closer second-place position would have required a few improvements to New Zealand’s tax system. While the incoming government’s restoring interest deductibility for residential property businesses was likely to have improved New Zealand’s score, the government removed depreciation for commercial buildings at the same time. Pretending that commercial buildings do not depreciate seemed likely to hurt our score, with some risk of Switzerland leapfrogging us.

Tax system scoring, like the Tax Foundation’s, helps provide a bit of perspective on how any country’s tax system rates against others, on what good tax policy looks like, and on ways of improving the coherence of the tax system.

It can also help remind us of things we might otherwise take for granted about our own tax system.

The Tax Foundation promotes four basic principles for tax policy. Taxes should be simple, rather than complicated. They should be neutral across types of economic activity, rather than intentionally or unintentionally promoting some kinds over others. Taxes should be stable, enabling reasonable investment and retirement planning. And they should be transparent.

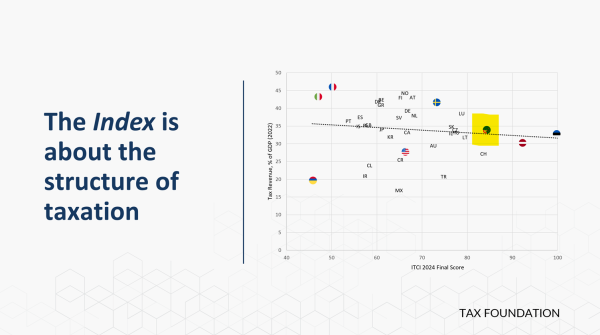

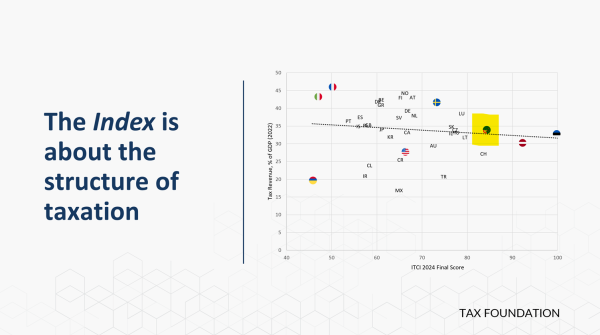

The Foundation’s Index is more about the structure of taxation rather than the tax take per se. The more a country relies on taxes that cause economic distortions, the worse its score will be.

The New Zealand government took in more tax revenue, as a proportion of overall economic activity, than some fourteen countries with worse-ranking tax systems than ours. Estonia’s top-ranked tax system collected almost as much revenue for its government as New Zealand’s, relative to the size of its economy, but more efficiently. If Estonian voters wanted their government’s spending (and tax revenue) to increase, their country could more easily bear that burden.

Click to view - Source: Tax Foundation webinar

New Zealand maintained its third-place ranking in this year’s index, but only just. In absolute terms, we dropped very slightly while Switzerland improved its position; it’s now really rounding error between the two.

We can draw a few lessons from this year’s benchmarking exercise.

First, and as most of us really ought to already appreciate, New Zealand’s GST is the best in the world.

For economists who study tax, the ideal consumption tax covers all final consumption rather than exempting bits and pieces for political point-scoring. Combining a flat GST with a progressive income tax (as New Zealand does) or with tax credits for lower-income households (as Canada does) provides a more efficient progressive tax system.

Exempting some spending from GST adds a lot of complexity to the tax system while chewing holes into the tax base, making it harder for the government to collect revenue.

And remember that a consumption tax like our GST does not care whether the money you spend is from wage and salary income, from interest earnings, from capital gains, from borrowing against your house, from illegal activities that you might not have reported as income, or from an inheritance. Once it’s spent, it’s taxed.

Only Korea’s consumption tax outranked ours, but not because it is better designed. The Foundation’s scoring on consumption taxes combines the tax rate and its relative tidiness. New Zealand’s is the tidiest, and that helps us rely less on other worse taxes – which would have boosted our score in other areas.

So: do not mess with our GST. Whatever objective you might want to achieve by tinkering with GST is better achieved in other ways, and with less risk of causing the whole thing to unravel with each exemption helping to justify the next one.

Second, New Zealand’s corporate taxes are a bit of a mess, putting us 30th out of 38 countries.

Ideally, corporate taxes are levied only on net revenue – that is, revenue after expenses. If tax rules mean that companies cannot fully count the real cost of investments in plant, machinery, and buildings against their earnings, their effective tax rate winds up being higher than the official rate – and our official company tax rate is high to begin with.

The Tax Foundation noted that while the UK made full expensing for machinery and equipment a permanent part of its tax code in 2023, New Zealand completely abolished capital allowances for commercial buildings.

All of it means that companies have less incentive to invest here, particularly in capital equipment, and especially in commercial buildings.

Poor council ratings systems worsen the problem. The Tax Foundation recommends that property taxes be based solely on land value, rather than land plus capital. Council rating systems that generally penalise adding buildings to land mean New Zealand also winds up with a very poor rating on that aspect of our tax system.

We all have different views about how large a role the government should play in the overall economy and in redistribution. Whatever your preferred level of taxation, it is better that government raise needed funds in the least harmful way possible. The Tax Foundation has provided a few helpful pointers about mistakes to avoid, and improvements to consider.

Perhaps next year we will get really lucky. Not only would Budget 2025 make improvements that will put New Zealand in the running for a rise in the rankings, but the rankings themselves would be released during a test match at Basin Reserve. Lounging on the grass, torn between reading the next line of tax policy and the next delivery from Patel… what could be better?

Dr Eric Crampton is Chief Economist at the New Zealand Initiative. This article was first published HERE

Overtaking Latvia’s much closer second-place position would have required a few improvements to New Zealand’s tax system. While the incoming government’s restoring interest deductibility for residential property businesses was likely to have improved New Zealand’s score, the government removed depreciation for commercial buildings at the same time. Pretending that commercial buildings do not depreciate seemed likely to hurt our score, with some risk of Switzerland leapfrogging us.

Tax system scoring, like the Tax Foundation’s, helps provide a bit of perspective on how any country’s tax system rates against others, on what good tax policy looks like, and on ways of improving the coherence of the tax system.

It can also help remind us of things we might otherwise take for granted about our own tax system.

The Tax Foundation promotes four basic principles for tax policy. Taxes should be simple, rather than complicated. They should be neutral across types of economic activity, rather than intentionally or unintentionally promoting some kinds over others. Taxes should be stable, enabling reasonable investment and retirement planning. And they should be transparent.

The Foundation’s Index is more about the structure of taxation rather than the tax take per se. The more a country relies on taxes that cause economic distortions, the worse its score will be.

The New Zealand government took in more tax revenue, as a proportion of overall economic activity, than some fourteen countries with worse-ranking tax systems than ours. Estonia’s top-ranked tax system collected almost as much revenue for its government as New Zealand’s, relative to the size of its economy, but more efficiently. If Estonian voters wanted their government’s spending (and tax revenue) to increase, their country could more easily bear that burden.

Click to view - Source: Tax Foundation webinar

New Zealand maintained its third-place ranking in this year’s index, but only just. In absolute terms, we dropped very slightly while Switzerland improved its position; it’s now really rounding error between the two.

We can draw a few lessons from this year’s benchmarking exercise.

First, and as most of us really ought to already appreciate, New Zealand’s GST is the best in the world.

For economists who study tax, the ideal consumption tax covers all final consumption rather than exempting bits and pieces for political point-scoring. Combining a flat GST with a progressive income tax (as New Zealand does) or with tax credits for lower-income households (as Canada does) provides a more efficient progressive tax system.

Exempting some spending from GST adds a lot of complexity to the tax system while chewing holes into the tax base, making it harder for the government to collect revenue.

And remember that a consumption tax like our GST does not care whether the money you spend is from wage and salary income, from interest earnings, from capital gains, from borrowing against your house, from illegal activities that you might not have reported as income, or from an inheritance. Once it’s spent, it’s taxed.

Only Korea’s consumption tax outranked ours, but not because it is better designed. The Foundation’s scoring on consumption taxes combines the tax rate and its relative tidiness. New Zealand’s is the tidiest, and that helps us rely less on other worse taxes – which would have boosted our score in other areas.

So: do not mess with our GST. Whatever objective you might want to achieve by tinkering with GST is better achieved in other ways, and with less risk of causing the whole thing to unravel with each exemption helping to justify the next one.

Second, New Zealand’s corporate taxes are a bit of a mess, putting us 30th out of 38 countries.

Ideally, corporate taxes are levied only on net revenue – that is, revenue after expenses. If tax rules mean that companies cannot fully count the real cost of investments in plant, machinery, and buildings against their earnings, their effective tax rate winds up being higher than the official rate – and our official company tax rate is high to begin with.

The Tax Foundation noted that while the UK made full expensing for machinery and equipment a permanent part of its tax code in 2023, New Zealand completely abolished capital allowances for commercial buildings.

All of it means that companies have less incentive to invest here, particularly in capital equipment, and especially in commercial buildings.

Poor council ratings systems worsen the problem. The Tax Foundation recommends that property taxes be based solely on land value, rather than land plus capital. Council rating systems that generally penalise adding buildings to land mean New Zealand also winds up with a very poor rating on that aspect of our tax system.

We all have different views about how large a role the government should play in the overall economy and in redistribution. Whatever your preferred level of taxation, it is better that government raise needed funds in the least harmful way possible. The Tax Foundation has provided a few helpful pointers about mistakes to avoid, and improvements to consider.

Perhaps next year we will get really lucky. Not only would Budget 2025 make improvements that will put New Zealand in the running for a rise in the rankings, but the rankings themselves would be released during a test match at Basin Reserve. Lounging on the grass, torn between reading the next line of tax policy and the next delivery from Patel… what could be better?

Dr Eric Crampton is Chief Economist at the New Zealand Initiative. This article was first published HERE

1 comment:

How does NZ compare with other countries when it comes to taxing the profits that charities make. Actually I thought the basis for any charity was that it was none profit making and all money received, less Reasonable operating costs, was spent on the charitable work it was set up to do.

Post a Comment

Thank you for joining the discussion. Breaking Views welcomes respectful contributions that enrich the debate. Please ensure your comments are not defamatory, derogatory or disruptive. We appreciate your cooperation.